"I believe in anniversaries," says one character in late playwright Sarah Kane's psychodrama "Crave." "That a mood can be repeated even if the event that caused it is trivial or forgotten," the character continues, adding, "in this case it's neither."

Today, Sept. 17, is an anniversary and the event that caused it is neither trivial, nor forgotten. This day, two years ago, Occupy Wall Street first inserted itself into the streets of lower Manhattan and the broader public consciousness. But I will not be celebrating the anniversary of Occupy Wall Street: I will not go to Zuccotti Park today and I will not attempt to repeat the mood of fight, energy and unbounded possibility and impossibility that electrified New York and beyond in Occupy's first flush two years ago.

The impetus and collective action that arose around the first "Sept. 17" were neither trivial, nor forgotten (shit is, after all, still fucked up and bullshit). An Occupy anniversary -- a calendar date to relive and repeat -- is all too possible as an event, and that's why I won't be going.

As I pointed out consistently at the time, and as writer Nathan Schneider stresses again in his new book, "Thank you, Anarchy," there was no one Occupy. That strange constellation of camps, rallies, street marches, meetings and relationships meant many things with varying potency to those involved. But above all for me, Occupy was about rupture: In the bold and basic act of taking space in New York's overdetermined grid, we found ourselves, each other and our streets anew. "Whose streets? Our streets!" we would chant. And sometimes -- when the police had lost control and we stormed across thoroughfares usually reserved for the constant flows of cars, work and consumption -- it was true; the streets were ours.

It's beyond the purview of these paragraphs to detail why Occupy was stunted -- I have no interest in debate over whether we should have built a program, platform or party. For me and many others, that was never the Occupy we loved or sought. (Call me an anarchist.) Suffice to remember that militarized police forces across the country, and especially in New York, cracked down on Occupy encampments and marches with overwhelming force and regularity.

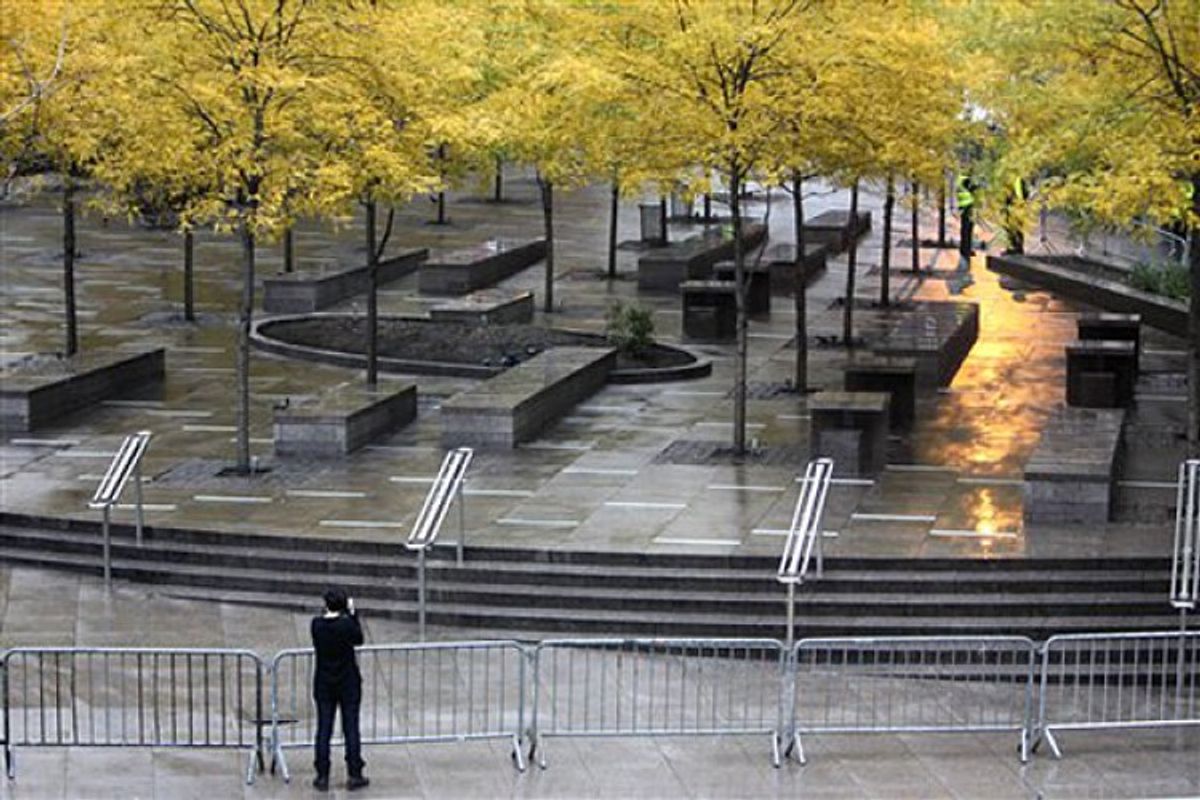

In preparation for today, Occupy's so-called second anniversary, police barricades have been stacked up and waiting to surround Zuccotti Park. It's now a familiar dance between protesters and police who are now practiced in the prevention of occupation of New York's "public" spaces. Hundreds if not thousands of Occupy anniversary attendees will gather in Zuccotti Park today to dance the same old dance. I too know the steps and that's why I won't be taking part.

Loath as I am to agree with philosopher-clown Slavoj Zizek, he has long decried the tendency of radicals and activists to come together to fondly remember the good old days of insurrectionary fervor they once shared. No doubt, the Occupy anniversary is not meant to be any such commemoration in service of nostalgia; organizers truly hope to reignite the sort of energy that fueled Occupy in late 2011. But on Sept. 17, 2011, Zuccotti Park was not even the first-choice resting place for the ambling crowds -- it was third on a list. That day, and those that followed, were crucially unbounded and unfamiliar. Going back to Zuccotti Park today, where the police are ready and waiting and events seem all too constrained (a "People's Exchange" after work hours, a march to demand a Robin Hood tax on Wall Street); the familiar fare contains little promise of rupture.

When robocop police bore down on Occupy camps, and evidence later emerged about vast federal surveillance of activities, it seemed to evidence one thing, at least: Occupy was felt as a threat -- and so in many ways was a threat -- to the sociopolitical status quo. In my humble opinion, it stopped being threatening when it became predictable. Media confusion around the refusal by most aspects of Occupy to issue demands or goals rendered the Occupy constellation unwieldy, uncontainable and unknowable.

Anniversaries by their very nature are contained. Indeed, Bastille Day, when first established, was not about storming the Bastille, but the birth of the modern French nation. Now the anniversary yearly sees the largest military parade in Europe proceed formally down the Champs-Élysées and millions of dollars' worth of fireworks erupt around the Eiffel Tower. In Britain on Guy Fawkes, young children learn the verse, dated back to the 18th century, "Remember, remember! / The fifth of November, / The Gunpowder treason and plot; / I know of no reason / Why the Gunpowder treason / Should ever be forgot!" and family-friendly bonfires burn effigies of Guy Fawkes. Anniversaries marking revolution and dissent have historically been apparatuses to defang the very insurrectionary impulses that gave rise to the original event.

I wish well to the attendees of today's Occupy anniversary activities in New York. And, in the original spirit of Occupy, if events take a surprise, unruly, unpredicted turn, I'll meet you in the streets. Otherwise, I will recall that other slogan of Occupy's heady days, borrowed from the pages of Herman Melville's "Bartleby the Scrivener": "I would prefer not to."

Insofar as Occupy once represented a terrain of possible rupture, it was about not repeating past patterns; it was about not going home (the fact of ad hoc encampments made this clear) but home understood as psycho-geographic location too: We would not return to the old ways of politicking and living, was the thought. Many of us have gone home since Occupy's first flourish was quashed and quieted. But returning, like dutiful mourners, to the drab concrete slabs Occupy once called home is the most profound act of "going home" possible -- seeking life from a grave. In a simple but perfect tautology uttered by James Franco's character, Alien, in "Spring Breakers," the problem I have with an Occuversary is crystallized: "If you want to go home you can go home but then you're just going to be home."

Shares