If you take the long view of Washington's ungovernability -- and when you're as old as I am and live on the other side of the Atlantic as I do, the long view is all you've got -- you have a particular insight as to how we got here.

Much of the problem can be traced back to events that took place exactly 40 years ago (Oct. 20, 1973): the Saturday Night Massacre, a major turning point of the Watergate scandal.

The next day, banner headlines across the entire front page of The New York Times read:

NIXON DISCHARGES COX FOR DEFIANCE;

ABOLISHES WATERGATE TASK FORCE

RICHARDSON AND RUCKLESHAUS OUT

It took a helluva lot to get that kind of coverage that autumn.

While Americans went about their weekend business, while the October war in the Middle East rumbled along, a mere 10 days after his vice president, Spiro Agnew, resigned over charges of tax evasion, President Richard M. Nixon raised the stakes in his fight to keep the truth about his involvement in the scandal and its subsequent cover-up secret.

It's tough to summarize all the events of Watergate, from burglary to the president's resignation. Woodward and Bernstein's "All the President's Men" is 349 pages long and I'm sure both of them still agonize over what they had to leave out. But the narrative's main turning points were on legal ideas related to executive privilege and judicial independence in the Constitution and the statutes and case law that underpin these ideas.

A recap of events for those who have forgotten -- or never learned:

In May of 1973, Archibald Cox, a law professor at Harvard, was appointed "special prosecutor" to independently look into the Watergate scandal. The appointment was made by Attorney General Eliot Richardson, himself a Harvard man, who had only just taken up the attorney general post, following the resignation -- because of Watergate -- of Richard Kleindienst, another Harvard law graduate.

Richardson had pledged in his confirmation hearings to give the special prosecutor complete independence -- including subpoena power -- to follow the evidence wherever it led. A few months later it led to the Oval Office when it was revealed in a Senate hearing on Watergate that Nixon was recording all conversations there. Cox issued a subpoena demanding that Nixon turn over the tapes. Claiming executive privilege, Nixon refused and offered a compromise: a Republican senator would listen to the tapes and provide a summary. Cox turned down the offer and stood by his subpoena power.

That was on a Friday. Presidents don't need high-priced media advisers to tell them that if they're going to do something unpopular they should do it on the weekend, when interest in the news is at a low.

Late Saturday afternoon, the president ordered his attorney general to fire Cox. Richardson refused and resigned. Nixon then ordered Richardson's deputy, William Ruckleshaus (you guessed it, another Harvard man), to fire Cox. Ruckleshaus refused and resigned.

The onerous task next fell to the country's solicitor general, Robert Bork (not a Harvard man). Cox was fired, his offices sealed, and the FBI sent in to seize papers. All of this took place in the space of a few hours that Saturday evening.

The outrage was immediate: New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis reported the incident the next day and took aim at Nixon's chief of staff, General Alexander Haig. Lewis wrote that Haig told Ruckelshaus: "Your Commander in chief has given you an order." The columnist went on, "There it was, naked: the belief that the President reigns and rules, that loyalty runs to his person rather than to law and institutions. It is precisely the concept of power against which Americans rebelled in 1776 and that they designed the Constitution to bar forever in this country."

And if you think Lewis was just an overwrought liberal, a more dispassionate observer, Fred Emery, wrote in The Times of London: "Over this extraordinary weekend, Washington had the smell of an attempted coup d'etat …. Last night as the FBI men moved in without warrant to "seal" the Cox files, the whiff of the Gestapo was in the clear October air. Some of the soberest men in government and out are now privately expressing anxiety that the military might now intervene -- either to back the President or throw him out."

For the first time since Watergate erupted, a plurality of Americans thought Nixon should be impeached. The calls for impeachment came from legislators as well -- and not just Democrats; a fair number of Republicans joined in. They did so to preserve a basic, nonpartisan precept of our democracy: The president is not above the law.

Nixon was as good as gone after his Saturday Night folly. Although it took some time. The law, when every "i" is being dotted and "t" crossed, can be a slow-moving machine. Ultimately Nixon ran out of legal maneuvers and had to resign. But the game was over on the Sunday morning after the Saturday Night Massacre.

But was that the end of the story?

No.

The conservative movement never really liked Nixon. He initiated detente with the Soviets, visited Mao in China -- rather than bombing both countries. He raised taxes. But conservatives also saw him as a martyr to "liberals" and their lap-dogs the press. He also flew the flag for executive-branch power. Conservatives believe in a strong a executive branch -- when a Republican is president.

The wound from one of their party -- if not one of their own -- having been driven from office is one that has never stopped festering for the Republicans.

Two Democrats in the last 30 years have made it to the White House: Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Special prosecutors and impeachment for real or as a threat hovered around them almost from the beginning of their terms of office. Republican payback?

There were other ways the Saturday Night massacre continued to play out.

In 1987, Robert Bork, the man who ultimately carried out Nixon's orders that autumn afternoon, was nominated by Ronald Reagan to the Supreme Court. Bork later claimed Nixon had promised to nominate him to the Court as the quid pro quo for firing Archibald Cox. Bork was rejected, in part, because of his willingness to fire the special prosecutor.

As Bork was being, well, "Borked," in another part of the Capitol Building hearings into the Iran-Contra scandal were going on. This affair was arguably much worse than Watergate. It involved the illegal sale of weapons to Iran with the proceeds secretly going to fund the contra rebels in Nicaragua -- both of which had been expressly legislated against by Congress. On the hearings panel, making the argument for unrestrained executive-branch power, was a congressman from Wyoming who had served in the Nixon White House, Dick Cheney.

Later, as George W. Bush's vice president, Cheney, given a helping hand by al-Qaeda's 9/11 attacks, took the position to its logical extreme. "When the president does it, that means it's not illegal" Nixon told David Frost at one point in their famous interviews. Cheney brought that philosophy with him to the Bush White House.

So how did this disgraced idea of unchecked executive power survive the Saturday Night Massacre and how did it lead to the current impasse in Washington? Here's an unprovable theory -- at least to professional historians -- but it makes sense to me. Five days after the Saturday Night Massacre, Nixon held a press conference. Deference had long since exited the relationship between the president and the reporters who covered him. Toward the end of the session the following interchange took place. A reporter asked: "What is it about the television coverage of you in these past weeks and months that has so aroused your anger?" Nixon answered, "Don't get the impression that you arouse my anger ... You see, one can only be angry with those he respects." He came back to the theme a few minutes later. "When a commentator takes a bit of news and then with knowledge of what the facts are distorts it viciously, I have no respect for that individual."

A four-decade-long war on the press's legitimacy had begun. The idea that it was a biased liberal press that made the molehill of Watergate into a mountain of Constitutional crisis took root.

A month later, an article in the New York Times quoted a letter to the editor written by one Lerline Westmoreland published in a Southern newspaper, the Memphis Commercial Appeal: "It seems to me that the greatest threat to this country is not so much a dictatorial Supreme Court or an imperfect President, it is a vicious, slanted news media on the minds of the masses of Americans who are either too lazy or too indifferent to think for themselves."

Under Reagan, Republican appointees on the FCC abolished the fairness doctrine, the obligation for broadcasters to air both sides of controversial issues. This led to an explosion of opinionated propagandists on the air waves relentlessly attacking "liberal" media. It continues to this day, degrading American public discourse.

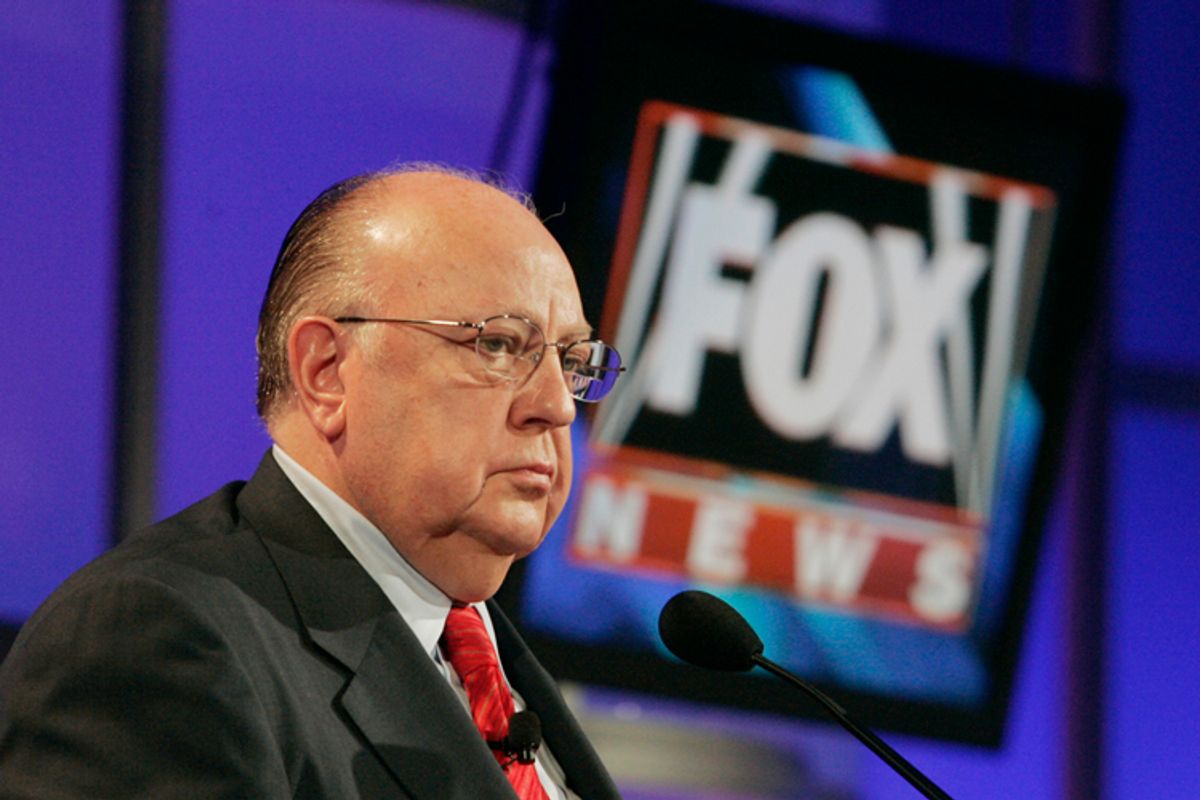

A Nixon media operative, Roger Ailes, discussed starting a Republican-slanted news program with the president pre-Watergate. Later, Ailes invented Fox News for Rupert Murdoch. Fox is one of the prime shapers of the hyper-partisan political culture that has made the U.S. practically ungovernable.

As I said, at the top, I take a long view from this side of the Atlantic. Over here, even Conservatives find themselves taken aback by the Tea Party and other extremist know-nothings who have been given the oxygen of publicity on Fox.

*

Only one of the principals of that evening in 1973 is still alive: William Ruckelshaus. Now in his 80s, he runs a foundation in Seattle and is still active in national life. He was then, and still is, a moderate Republican. I wrote to him and asked, "If you knew, that ultimately, President Nixon would be forced to resign and that future generations of Republican legislators would spend so much time trying to even the score, would you have taken a long view and done what was necessary to protect the president and keep him in office?" I didn't really expect an answer -- but within two days an email came back: "The answer is no." Mr. Ruckelshaus added, "I felt what he was asking me to do (fire Archibald Cox) was fundamentally wrong and unconscionable."

In Autumn 1973, it was still possible for Republicans and Democrats to come together and agree on a basic principle of government -- like the limits on presidential power. It is hard to imagine that happening today because of those events precisely 40 years ago.

Shares