EASTBOUND AND DOWN — the HBO comedy about a former major-league pitcher trying to regain the glory of his youth — seemingly has very little in common with Breaking Bad, AMC’s dark drama about a high-school chemistry teacher-turned-meth dealer. But at the center of both shows lies a charismatic, proud leading man who squanders his talent and moneymaking potential to wind up teaching in the classroom. Rather than lick their wounds, these characters set out to right this perceived wrong — even if, by doing so, they alienate the people they love the most.

When Breaking Bad’s leading man finally admitted to his wife, Skyler — and, more importantly, to the viewers—that he built his meth-making empire to fulfill his own ego, it was among the show’s most powerful moments. “I did it for me,” he said. (How long had we waited to hear Walter White say those words?) Of course, we had long figured out that Walt was lying when he said it was all for the family.

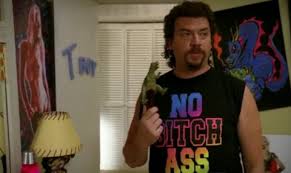

The fourth and final season of Eastbound and Down sets itself up much like a comedic counterpart to Breaking Bad. Instead of the major league pitcher he’s always aspired to be, by the start of the fourth season of Eastbound and Down, Kenny Powers has settled down with his wife, April, and Toby, the son he was left to reluctantly care for last season. Kenny’s a family man now; in the first episode of the new season, much is made of the fact that, while April’s working to become a top-selling real estate agent, loyal and caring Kenny’s the model husband and father. And yet, surprisingly, April hasn’t been relegated to the disapproving shrew—a stock character with which we’re all too familiar on television (many sitcom wives, like That 70s Show’s Kitty or even Curb Your Enthusiasm’s Cheryl, fit the bill, and this syndrome also extends to cartoons; Family Guy’s Lois and Marge from The Simpsons have screechy voices to boot). Unlike these other, unbalanced TV marriages, Kenny and April’s is a more equal partnership than we’ve come to expect from the show’s leading man, who tends to lord over his friends and family rather than engage with them.

But here’s where the Power of Television — with its acid-like ability to eat right through our good sense and moral righteousness — comes into play: We actually feel bad for Kenny. I did, anyway, watching him sit through a dinner party in the season four opener with April, who goes on about what a wonderfully supportive partner he’s been—“You’re like a nice, big bra,” one guest offers. But, like circa-2010 Miley Cyrus, Kenny can’t be tamed. Powerful when he’s pissed off (and as a self-proclaimed Messiah figure), Kenny’s never more pissed off than when he feels belittled. In the show’s first season, when Kenny returns from Seattle to his hometown of Shelby, North Carolina, after washing out as a pitcher in the major leagues, and takes a job as a high-school gym teacher, his fall from the top bruises his ego, setting him off on a rampaging quest for stardom. He all but destroys his relationship with his brother, who makes the mistake of opening his home and subjecting his wife and kids to Kenny—who repays his brother by smashing his furniture and DVD player in a self-loathing rage. Playing professional baseball is the only thing that gives Kenny a sense of self-worth. As he says in the pilot, “All of my successes depend on me. I’m the man who has the ball; I’m the man who can throw it faster than fuck.”

* * *

Teachers have long been derided as “those who can’t do,” but it’s relevant that teaching—which, of course, Walt also falls back on when he fails to become a hotshot chemist—is typically a predominantly female occupation. By rejecting this vocation for pursuits that project an image of machismo—Walt dabbles in drugs, Kenny in the less hazardous game of baseball—both men enact a particular fantasy of male power. Breaking Bad and Eastbound and Down premiered, respectively, in 2008 and 2009, at a time of financial crisis during which the effects of the five or six million manufacturing jobs lost in the first decade of the 2000s—real, manly jobs dominated by real, manly men—were ripe for fictional exploration.

Shows like Breaking Bad and Eastbound and Down fixate on caricatures of male ego. Walt’s pride is so badly damaged that he’s willing to literally risk everything for a taste of something more, and Kenny is constantly casting himself in a mythical light, comparing himself to a god of the sea or Luke Skywalker. We may know in our hearts that these characters are ultimately self-serving, yet—to get back to that devious Power of Television—we cheer them on anyway. Towards the end of Breaking Bad’s five-season run, the Internet was full of hand-wringing over the fact that lots of fans were actually rooting for Walt, despite all the death and destruction we know he is responsible for. Part of that cheerleading can be chalked up to the viewer’s identification with a show’s central figure. But there’s something more complex in viewers’ reaction to characters like Kenny Powers and Walter White. As these characters attempt to fulfill the American promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness at all costs, they take on that burden for those of us sitting at home, watching, who don’t have the balls to do it ourselves. And look at what they turn to in order to fulfill that dream: meth and baseball. Doesn’t get much more American than that.

At the end of Eastbound and Down’s third season, Kenny finally gets a chance to pitch for the major leagues, and he leaves it—literally walking off the mound mid-game—to be with April and Toby. The fact that the series was supposed to end there, with Kenny abandoning his finally successful baseball career for his family, turns him into an allegory for the show itself, which was supposed to end after its third season before HBO unexpectedly gave it a fourth: Witness the resurrection of Kenny Powers.

* * *

So far, the fourth season points to a very different endpoint for the character than that suggested by the season three finale, in which responsible domesticity triumphs over an exciting career (and strippers and drugs and Jet Skis). Rather than family being the final refuge, it becomes a launching pad for Kenny’s professional goals with April’s support to head back into the game. Perhaps she knows what Skyler began to suspect as Walt’s lies piled up: For this man, family isn’t enough.

Though I liked the way the third season of Eastbound and Down ended, I’m glad HBO gave the show another stab at its series finale. The final season—which begins, as all the seasons did, with Kenny on a quest for baseball supremacy—sets up a better, more honest ending because it acknowledges that he won’t be satisfied with a stable home life. Like Walt’s breathtaking confession to Skyler, Kenny’s isn’t a noble acknowledgement. But it’s a step in the right direction for TV’s favorite hero, the middle-aged white guy. As a long-time TV enthusiast and a resident of the real world, I need to hear that Walt and Kenny crave more out of life than their perfectly lovely family lives have to offer. Their solution to this middle-aged ennui is to enact a fantasy that, in pop culture, and television especially, has traditionally been reserved for men, usually white. (Women on TV break bad in different, generally much more banal, ways than men. Those who try to carve their own path usually find a way to manage their home lives while pursuing their dreams—like Lizzy Caplan’s Virginia Johnson on the new Showtime series Masters of Sex—or else they have refused to build a family life at all—like Homeland’s Carrie Mathison or Michelle Simms, the spunky heroine of the sadly cancelled Bunheads.)

On Breaking Bad and Eastbound and Down, all is not right at home—and that’s an exciting possibility for the future of TV. You can break pretty much any show down to a basic family structure—even shows like Cheers and Friends, it’s long been argued, have taken a cast of loosely connected people and used it to recreate family dynamics. The raucous endpoints of Walt and Kenny’s trajectories, which seem to unfold like an ever-louder temper tantrum, at least give voice to the lie that everyone eventually finds what they need out of life from their families. For some people—maybe even a lot of people—that’s just not true.

Ultimately, what these men want is not a loving home base but a sense of freedom and control over their lives, even if this comes at the expense of the families in which they’ve invested so much time and love. They might be sad or pathetic or selfish—not to mention self-destructive—or all of the above. But by filtering the ugly reality of their middle-aged crises through TV’s mollifying prism, Eastbound and Down makes room for a new kind of hero. Protagonists like Kenny Powers and Walter White may allow us to vicariously enjoy the kind of freedom they espouse, but they never let us forget that it all comes with a heavy cost. They show us that no one—not even a white man—can have it all.

Shares