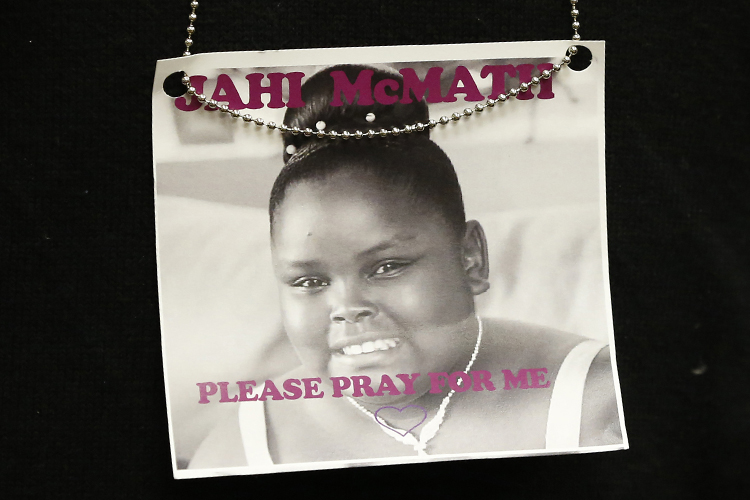

Jahi McMath is dead. The 13-year-old was declared brain dead on Dec. 12, three days after a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy to treat her sleep apnea resulted in “heavy bleeding, cardiac arrest and whole brain death.” The Alameda County coroner’s office issued a death certificate for her. And the New Beginnings Community Center says she “has been defined as a deceased person.” Yet there is no funeral planned for the girl, no memorials in her name. Instead, she has been moved to a facility where she receives “nutritional support, hormones and antibiotics to combat infections,” a place where family attorney Christopher Dolan says she is “going to be treated like the innocent little girl that she is, and not like a deceased body.” But while the recent battle over what to do with what remains of the once vibrant teen has for now been settled, the ethical questions over her case – and of what constitutes life and death – remain.

Last month, two Children’s Hospital Oakland doctors and three outside physicians brought in by the girl’s family declared her brain dead. But the girl’s family fought the hospital’s decision to remove her from a ventilator, and launched an Alameda Superior Court battle to keep her on support. On Sunday, the hospital released McMath to the Alameda County coroner’s office – which then transferred her to a facility that promised, as the family lawyer says, “all of the healthcare that any human being should deserve to have.” The family initially said it would not reveal the girl’s location because “We’ve had people make threats from around the country,” but New Beginnings issued a statement thanking the public for its “concern about this little angel who deserves a chance to be cared for with dignity and respect.”

On Fox News Monday, Bobby Schindler, the brother of Terri Schiavo — the woman whose persistent vegetative state launched a 15-year court battle — said, “Our family, our foundation, want to stand with this family and say, ‘This girl needs a chance.'” In an essay for CNN last month, medical ethics professor Robert M. Veatch — who was an expert witness in the similarly thorny Karen Quinlan and Baby K cases — argued for a “conscience-based” approach to matters of life and death. “If the patient does not suffer, and private funding is available, people should have the right to make this decision for their loved ones,” Veatch says. McMath’s family has so far raised almost $55,000 for her life support. “Society should show sympathy for mothers who want their children to be kept alive.” And as the mother of a 13-year-old daughter myself, I can’t imagine the agony of McMath’s family right now.

But the precedent this case sets is an unnerving one. And as Arthur Caplan, director of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Langone Medical Center, told the L.A. Times in December, “I think it’s disrespectful to the dead in a fundamental way, and it opens the floodgates for other people to say, ‘Oh, you don’t really know when we’re dead, do you? So please make more efforts for my loved ones.'” Just because it’s financially feasible to keep up the appearance of life doesn’t make it ethically responsible. And writing in the Atlantic two years ago, neurologist Richard Senelick explained the difference between a vegetative state and brain death and said, “No one who has met the criteria for brain death has ever survived — no one. It can be difficult to predict a person’s outcome after a severe brain injury, but it can be said with certainty that a brain dead individual is dead, the same as if their heart was not beating.”

Jahi’s uncle Sealey told Piers Morgan recently that “I’m just still praying that one day I’ll be able to see her smile again.” The hardest thing in life is to let go of it, to accept you’ll never see that person’s smile again or hear her laugh. It hurts beyond measure. A ventilator can make a person seem alive: a 2008 bioethics report notes “A beating heart, warm skin, and minimal, if any, signs of bodily decay — are a sort of mask that hides from plain sight the fact that the biological organism has ceased to function as such.” It can’t, however, bring back a smile. It can’t make a girl who’s been declared dead not be dead. Hope can be a fiercely cruel thing. And when you can’t stave off the inevitable, the best you can wish for isn’t a medical miracle but another kind of miracle: consolation. As Children’s Hospital said in its statement to the family, “We wish them closure and peace.”