Last week, conservative Bloomberg columnist Megan McArdle and American Enterprise Institute fellow Scott Gottlieb debated New York magazine's liberal columnist Jonathan Chait and former Assistant Surgeon General Douglas Kamerow over the proposition that Obamacare is "beyond rescue."

If you have an hour and a half of free time and a nearby brick wall to repeatedly smash your head into, you can watch the whole debate here. In the event that you're unfamiliar with Salon dot com, suffice to say, I stand with Chait and Kamerow.

I didn't write about this earlier because, even though McArdle and Gottleib won the debate in the eyes of those in attendance, I thought the proposition (which presumably they didn't pick) was almost impossibly unfair to them. They had to convincingly argue that Obamacare had fallen into a persistent vegetative state; Chait and Kamerow could win simply by convincing people that it might come out of its coma at some point.

But then on Tuesday, McArdle imported many of the comments and arguments she used on the debate stage into a column called "Resolved: Obamacare Is Now Beyond Rescue," so if she at any point believed the burdens of proof were stacked unevenly against her, I think it's fair to assume that like so many conservatives she's now completely certain that her position is correct and her arguments unassailable. Obamacare is beyond rescue.

I think this is almost definitionally wrong for two reasons, one technical and one philosophical.

Chait addressed the first pretty elegantly in his presentation, so I'll more or less recapitulate his argument. Obamacare's an insurance system intended, for now, to patch a large hole in the country's safety net, which creates healthcare guarantees for most but not all Americans. It could in theory be expanded as other programs are phased out or incorporated in, but that's a question for future years.

The system works by guaranteeing that uninsured people can buy private, regulated coverage; providing them subsidies on a sliding, so that the plans on the market are relatively affordable; and penalizing them if they opt out. A system like this becomes "beyond rescue" if very few people enter it, or carriers pull out of it en masse, or perhaps a combination of the two, precipitated by an actuarial death spiral, where an unexpectedly ill client base causes insurers to increase premiums, driving more healthy people out of the market until it fails altogether.

Obamacare might also be beyond rescue if its political liabilities are so severe that Congress will ultimately be forced to replace or repeal it, regardless of the system's functionality.

Anything short of these kinds of critical failures belies McArdles premise.

That obviously doesn't mean Obamacare hasn't fallen short of expectations in any way. It obviously has, in many. McArdle's presentation and follow-up article both include litanies of embarrassing screw-ups that have plagued the rollout. And though we can't know for sure just yet, it's likely that the coverage expansion will be smaller in the first year than originally anticipated. There are a lot of reasons for that. Healthcare.gov's two-month outage is a big one; insufficiently generous subsidies is another. An active and ongoing campaign to discourage enrollment and block the Medicaid expansion in Republican-run states is a third.

But there will be a coverage expansion. In fact there almost certainly already has been one. In her oral presentation, but not in her argument, McArdle lent credence to a particularly dishonest conservative claim that there may right now be fewer people with insurance than there were before Affordable Care Act benefits kicked in on Jan. 1, because more people may have had their old policies canceled than enrolled via state-based exchanges. This is a false analogy built on dubious numbers. The people whose policies got canceled didn't all meet up at Tea Parties to burn their Obamacare cards. What's likelier is that most of them transitioned into new coverage, either directly through their old carrier, or through a new carrier, or on the exchanges before their old plans lapsed. And we have some new data that's consistent with this argument.

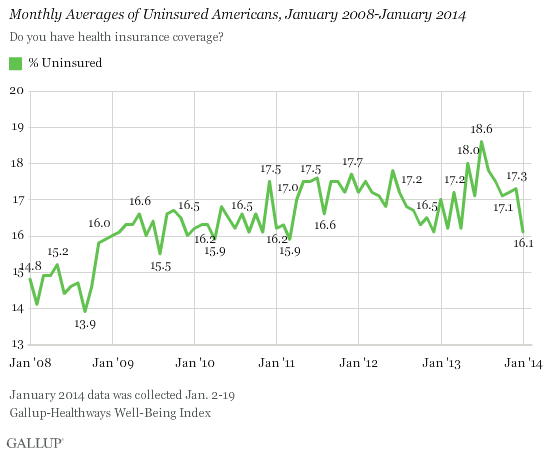

It's noisy and inconclusive. But the important bit is the downward slope at the end of the graph, which is consistent with the proposition that Obamacare is contributing, as intended, to a reversal in a secular trend of increasing uninsurance.

Maybe future developments will drive Obamacare into genuine failure -- McArdle's article also includes a litany of political challenges Obamacare has yet to face -- but it's not inexorably headed toward one right now. It's not about to be repealed or replaced, and a death spiral is probably not going to happen.

So as a technical matter we're almost definitionally left to conclude that Obamacare isn't beyond rescue, and may not ever need rescuing, even if it's endured severe implementation turbulence and (at this ridiculously early stage) fallen short of coverage expectations.

But I think this analysis is so dug in to the particular architecture of Obamacare, and the benchmarks required to sustain it, that it's become disconnected from the more-important conceptual purpose of national health insurance. The purpose of Obamacare isn't to test the government's ability to create an actuarially sound risk pool, or to guarantee that everyone can keep their old insurance, or even really to hold down healthcare costs (though that is one of the law's major goals).

No, the purpose is to establish a coverage guarantee, so that nobody's left bankrupt or dead due to certain vicissitudes outside of their control. Losing a job or getting sick shouldn't consign anybody to the risk of medical bankruptcy. All people should be able to go to the doctor without experiencing tremendous financial duress. Ramping up Obamacare enough to halve the number of people who are vulnerable to misfortunes like these might take longer than expected. But the guarantee already exists. A very durable political coalition supports it, and will continue to support it even if the system through which it operates comes crashing down. And if it does come crashing down, whatever Congress decides to build atop the wreckage will have to preserve the guarantee. In that sense Obamacare has already succeeded.

Shares