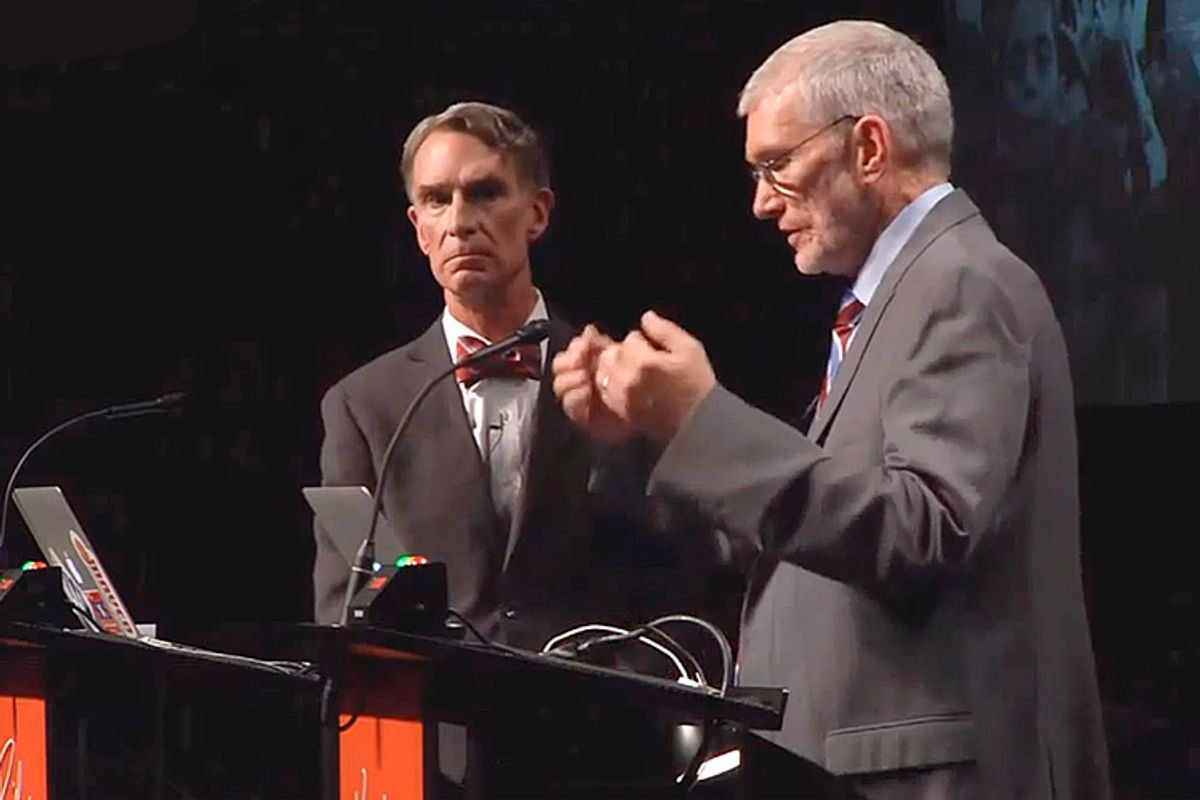

The much-anticipated debate between science guy Bill Nye and creationist-in-chief Ken Ham finally occurred Tuesday evening, and what a strange creature it was. The moderated debate, hosted at Ham’s headquarters in Kentucky, lasted almost three hours, and featured a mixture of long speeches, timed responses, powerpoint presentations, and questions from the audience. Each opponent adopted the tone one likely would’ve expected, with Nye coming off as meticulously polite but exasperated with the lack of rigor in Ham’s claims -- and Ham affecting the usual weird condescension of the Young Earth Creationist crowd, who seem to imagine evolution is not only wrong but silly.

Unsurprisingly, the predictable set-up gave way to predictable results. Nye referenced wide swaths of research on rocks, landforms, trees, and ice; Ham produced alternative explanations for some of Nye’s claims and not others, all the while roundly declaring that the past is essentially unknowable to us. From time to time, Ham refused to engage with Nye or the opposing side altogether; when presented with an audience question asking how he would respond to a hypothetical world in which evolution was proven to be true, Ham merely replied that such a thing could never happen.

It would be easy enough here to call Ham’s intelligence into question and berate him for so thoroughly and publicly missing the point of a hypothetical. But this evasion was only one of many refusals of engagement, which calls into question why, if Ham is convinced of the shoddiness of evolutionary science, he would avoid delving into the particulars of its problems. Indeed, the two men talked past each other for the entire evening: if Ham were really crusading to reveal the utter bankruptcy of evolutionary science, why would he let that happen?

The answer has to do with the category of project Ham’s activism falls under. It is not a scientific project, nor even one much related to knowledge of the natural world, scientific or not. Ham’s project is rather best understood as an ethical one.

At one point in his speech, Ham produced a PowerPoint slide with two opposing columns. On the left, “man’s ideas” gave rise to moral relativism, which in turn tossed the concept of marriage into confusion, allowed for euthanasia, and encouraged abortion. On the right, “God’s word” gave rise to moral absolutes, which support biblical marriage, the sanctity of life, and the notion that human life begins at fertilization.

Though this graphic contained no direct reference to evolution (it was subsumed under the evil heading of “man’s ideas”) it nonetheless explains most clearly why Ham is willing to challenge the idea so relentlessly and so publicly. Evolution, in Ham’s mind, provides for the possibility of a world without God, in which human beings are imbued with no special purpose. Alternatively, in the creationist frame, human beings are made, which means they are made for some things, rendering certain ethical practices superior and others inferior.

Evolutionary science as an alternative explanation for the origins of life poses a serious problem to that kind of ethics, however. If sex, for example, is merely an accident of nature rather than the handiwork of an intelligent creator, there’s really no way to use it wrongly, unless in the commission of some other moral harm. One of its capacities is to lead to procreation, but a failure in that capacity represents a mere fact rather than an injury. On the other hand, if sex is the design of an intelligent creator, then we can look to the intended purpose of the act to know whether or not we’ve wrongly employed it: for Ham, this would implicate rules about the genders of the persons involved, their marital status, and likely what if any contraceptive measures they choose to use.

This same logic applies to all of the moral ills Ham repeatedly brought up, which Nye seemed to struggle to respond to. After all, he came prepared for something resembling a scientific discussion, and was treated to a thinly veiled moral sermon. Thus, those already primed to be concerned with science likely went in and came out agreeing with Nye, while those primed to frame evolution as a threat to Christian ethics likely went in and came out agreeing with Ham.

Which is why debates of this kind are unlikely to be of any real use to either side, unless they’re merely intended to raise funds or sell books. A more fruitful debate would be between Ham or any member of his Young Earth Creationist cadre and a dedicated Christian ethicist who views both theism and specific Christian ethical imperatives to be consonant with the theory of evolution.

Over and over again, Nye raised the existence of such persons, and asked Ham to explain how it is that so many faithful Christians do not object to evolution. Ham never produced a response, other than to say, vaguely, that majorities can be wrong. But majorities can also be right, and the fact that Ham could not even venture to imagine himself hypothetically as an ethical Christian who regarded evolution as likely or true underscores the real heart of his project: this isn’t about whether or not schools should be skeptical of science, it’s about whether or not goodness can be argued for outside a Biblical literalist framework.

It can be. The Catholic Church, which has broadly approved of the theory of evolution, nonetheless maintains highly detailed Christian ethical positions on issues from marriage to abortion to wages and poverty. Many Protestant churches, such as the Church of England and the United Methodist Church, also manage to articulate coherent ethical positions while maintaining that evolution is a viable theory. And this is why it comes down to Christians to handle people like Ham: he really is our concern, and his fears and the fears of those who believe as he does should be answered. So long as he can point to those who do not believe in God and have markedly different ethics than he does as the main proponents of evolution, his position that evolution ruins faith and Christian morality will appear at least superficially probable.

Shares