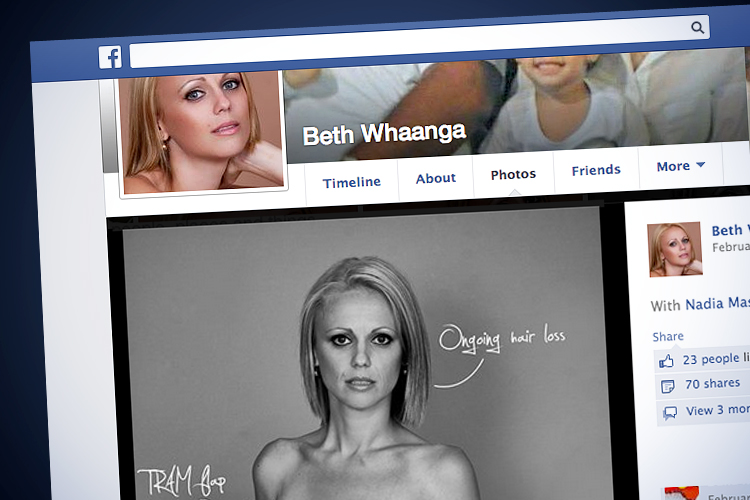

Beth Whaanga is a beautiful, blond, 30-something Australian woman. This week, she posted a photograph of herself in a fluttery red dress on Facebook. Then she posted a picture of what she looks like beneath that dress. And those seminude images created a stir.

The registered nurse and mother of four was diagnosed with “major cellular changes” and the BCRA 2 gene mutation last year, and like Angelina Jolie, decided to take radical action and have a double mastectomy. She calls herself “a breast cancer preventer” and says, “My life was not in danger, I didn’t have to fight … I was lucky enough to find these changes before they became aggressive or spread.” But her photos show evidence of, if not a fight, a profound experience nonetheless. They are helpfully annotated to explain what the viewer is seeing: the scars of “Total bilateral mastectomy.” The “Total hysterectomy.” The loose flesh of “Rapid weight loss.” The multiple little marks of drains and lumpectomies.

The photos, shot by Nadia Masot, come with the warning that “These images are confronting and contain topless material” but add, “They are not in anyway meant to be sexual … If you find these images offensive please hide them from your feed. Each day we walk past people. These individuals appear normal but under their clothing sometimes their bodies tell a different story.” The Courier-Mail reports that within hours of the photos going up, they’d been reported to Facebook. Encouragingly, Facebook has said it will not remove the images, but Whaanga meanwhile says she has been unfriended more than a hundred times. Over a hundred people looked at her and walked away.

Every encounter with illness is different, and Beth Whaanga’s choice to bare her scars is a personal one. Though Whaanga and Masot hope their act will attract other volunteers for their Under the Red Dress project, there’s no one right or extra-brave way to deal with the things that scare us. You don’t have to pose nude after your mastectomy any more than you have to dance around the operating room before it. But Whaanga’s willingness to show herself in such a public way is nonetheless impressive. We tend to prefer our breast cancer stories funny or sexy. When the visuals are painful or don’t have a happy ending, they get closed down. When the words of the person going through it don’t follow a particular script, she gets publicly shushed.

My own body is a litany of damaged terrain. The price of survival has been a large bald spot on the top of my head, a pale, playing-card shaped reminder of a skin graft on my thigh, and three distinctive surgical scars on my chest. Since my cancer, I’ve posed nude twice for different artist friends and kept the results mostly private. The experiences were terrifying and awesome. I did it because I’ve learned that being able to reveal ourselves when we’re our most imperfect is a big deal. We play out our own versions of “Beauty and the Beast,” asking, “Can you look at me, can you love me, just like this?” I’ve learned that takes trust and vulnerability, whether we’re showing our breasts or the tops of our heads. And that sometimes we’ll be rejected. Sometimes people will be offended by the complicated, messy humanity in front of them.

I will never forget how, during a family visit last year with an old friend who’s been through multiple serious surgeries, she found a private moment to lift up her shirt for me and show me the scars that run from below her chest to her pubic bone. Her lanky body is now a detailed map of close calls and ongoing treatments and hopes and disappointments and pain. And for all the accumulated hours we’ve spent talking about our respective medical adventures, it was that gesture that told me something uniquely intimate. It was that that said, “You can share in this; it’s OK.”

Beth Whaanga’s exposure won’t end breast cancer, though she makes a powerful case for genetic testing – and a powerful statement about the choices it can leave one to face. But new information released just Wednesday revealed that “the death rates from breast cancer and from all causes were the same in women who got mammograms and those who did not.” We’re still living and dying and going under the knife here. That’s not changing any time soon. And so Whaanga’s act isn’t just another “awareness-raising” stunt. It’s an invitation to look at each other with compassion. To see breast cancer as more than a jokey fight to “save the ta tas.” To accept each other, scars and all.