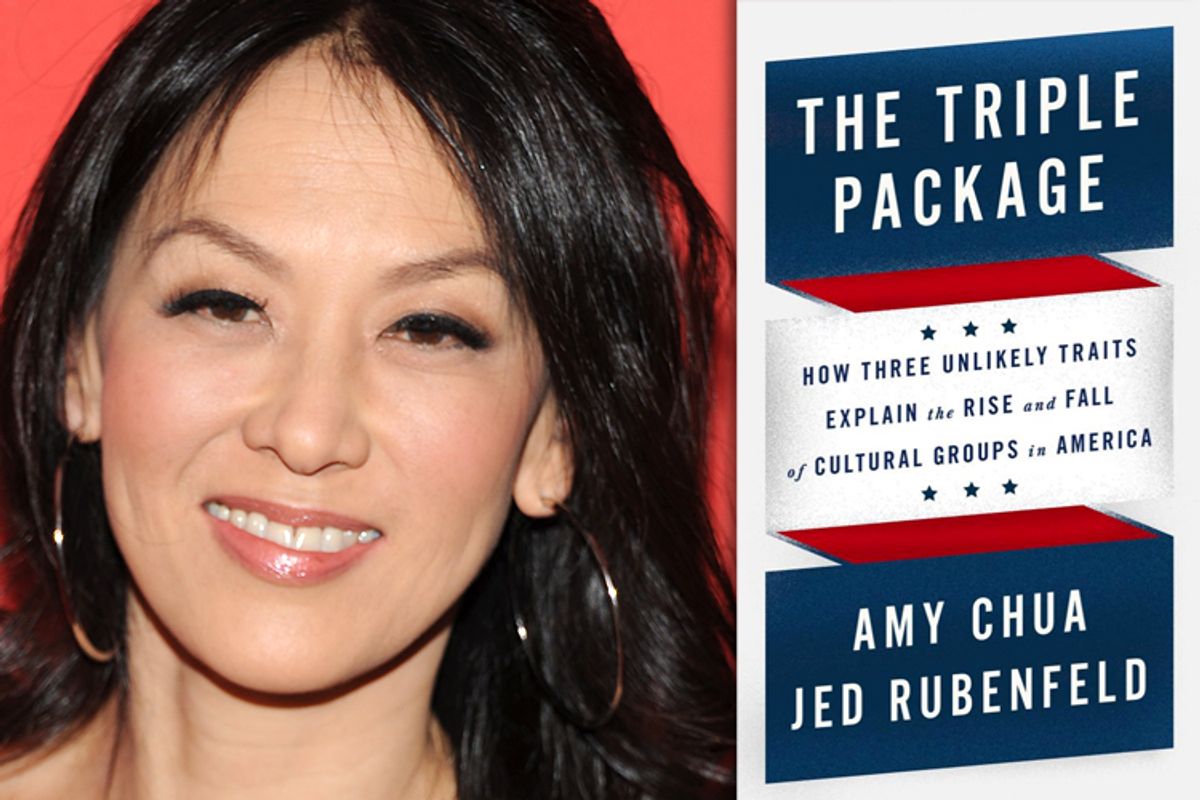

Here we go again. Tiger mom Amy Chua is back, reinforcing stereotypes and presenting glib solutions for attaining success. Her new book, "The Triple Package," jointly authored with husband Jed Rubenfeld, argues that certain ethnic and religious groups -- namely Jews, Indians, Chinese, Iranians, Lebanese, Nigerians, Cubans and Mormons – possess qualities that make them more likely to succeed in life. Chua and Rubenfeld claim that these groups have “three cultural forces” -- a superiority complex, insecurity and impulse control -- that drive them to achieve.

Aside from the innately offensive nature of such stereotyping, reviews and commentary have already pointed out that the book props itself up with flimsy data and questionable evidence. It comes as little surprise that Chua’s newest publication is accompanied by skepticism and controversy. Her previous book, "The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother," and its accompanying Wall Street Journal article made unfounded racial assertions and coined a parenting philosophy out of thin air. The terms “tiger mom” and “tiger parenting” entered our vocabulary, becoming shorthand for a strict, no-excuses style of parenting supposedly commonplace and traditional across Asian and Asian American households. This further reinforced the “model minority myth” of Asian American students as stellar accomplishers with an almost supernatural ability to overcome all odds and pull themselves up by their bootstraps to achieve the American dream. In reality, no one had heard of the tiger parenting philosophy before Chua wrote about it because, like the mythical “model minority,” it doesn’t exist.

In "The Triple Package," Chua pays lip service to debunking the model minority myth while continuing to capitalize on cultural stereotypes. To be fair, Chua and Rubenfeld appear earnest in their assertion that individuals of all backgrounds can tap into the “triple package” to attain success. They meticulously identify and attempt to address potential criticisms, including charges of ethnocentrism, prejudice and cultural superiority. They take pains to point out that “persistently low-income groups became poor because of systematic exploitation, discrimination, denial of opportunity, and institutional or macroeconomic factors having nothing to do with [lacking the triple package].” They stress that the Asian American community – which the book examines closely – is not monolithic, and that “there are black and Hispanic subgroups in the United States far outperforming many white and Asian subgroups.”

Yet Chua and Rubenfeld simultaneously conflate the experiences of different Asian subgroups, giving short shrift to ethnic differences even as they celebrate the purportedly unique values of some. For example, Asian immigrant groups that are not identified as possessing the “triple package,” such as Vietnamese, Koreans and Japanese, are nonetheless used in building the case for Chua and Rubenfeld’s theory. The authors even cite Korean American Yul Kwon, winner of the CBS reality show "Survivor," in making their case about Chinese culture.

"The Triple Package" boldly takes research findings out of context. In one circumstance, Chua and Rubenfeld rely on the work of researcher Vivian Louie to support their proposition that Chinese immigrants – including those who are low income – possess impulse control, one of the three triple package traits allowing them to succeed and transcend social class to attain upward mobility. However, a more careful read of Louie’s work indicates that while her working-class, immigrant Chinese subjects would indeed agree that hard work and educational excellence are keys to success, class barriers and lack of social capital in reality can block or impede their actual social advancement. Ultimately, Louie concludes that we need more research “disentangl[ing] immigrant status, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status” in understanding social mobility.

In fact, disaggregated data about Asian American students, recently released by education researchers Alejandro Covarrubias of Institute of Service-Learning, Power, & Intersectional Research and Daniel Liou of Arizona State University, explores these very interactions. This data, which dissects intersections of race with class, immigration status and gender, indicate that -- surprise, surprise – the triple package and "tiger parenting" do little to shield Asian American students from the obstacles to achievement and earning power felt by other groups.

Class, as usual, plays a significant role. Data also collected by the study authors reveals that 96 percent of Asian Americans with a family income of $100,000 to $149,999 graduated from high school, compared to only 81 percent of those with a family income of $49,999 or below. At the collegiate level, 37 percent of Asian Americans with a family income of $100,000 to $149,999 attained a bachelor's degree, compared to only 24.5 percent of those with a family income of $49,999 or below. The study also uncovered differences related to immigration status and citizenship, with undocumented Asian Americans having by far the lowest educational attainment, significantly below both United States-born and naturalized American citizens of Asian descent.

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics also indicates Asian American men have significantly higher income outcomes than their female counterparts across most degree achievement categories (except for baccalaureate degrees), and Asian American men also have more professional, doctorate or graduate degrees than Asian American women across the board.

Where does this leave tiger mom and those ethnic and religious groups “blessed” with the triple package? It’s well known that middle-class, professional parents of all backgrounds have more resources and social capital to foster their children’s academic achievement and extracurricular accomplishment than their lower-income, working-class counterparts. This is really what’s behind the stellar academic attainment of a limited group of predominantly middle-class Asian American students, and economic success of middle-class members of certain social groups.

"The Triple Package" implies that members of some ethnic and religious cultures are imbued with a natural propensity for success. Such broad, unsupported assertions hide inequality within communities that the authors are supposedly trying to praise. Equally dangerously, they promise easy answers where none exist. There is no magic bullet for winning, and reality is more nuanced than the world as seen through Chua and Rubenfeld’s eyes.

Shares