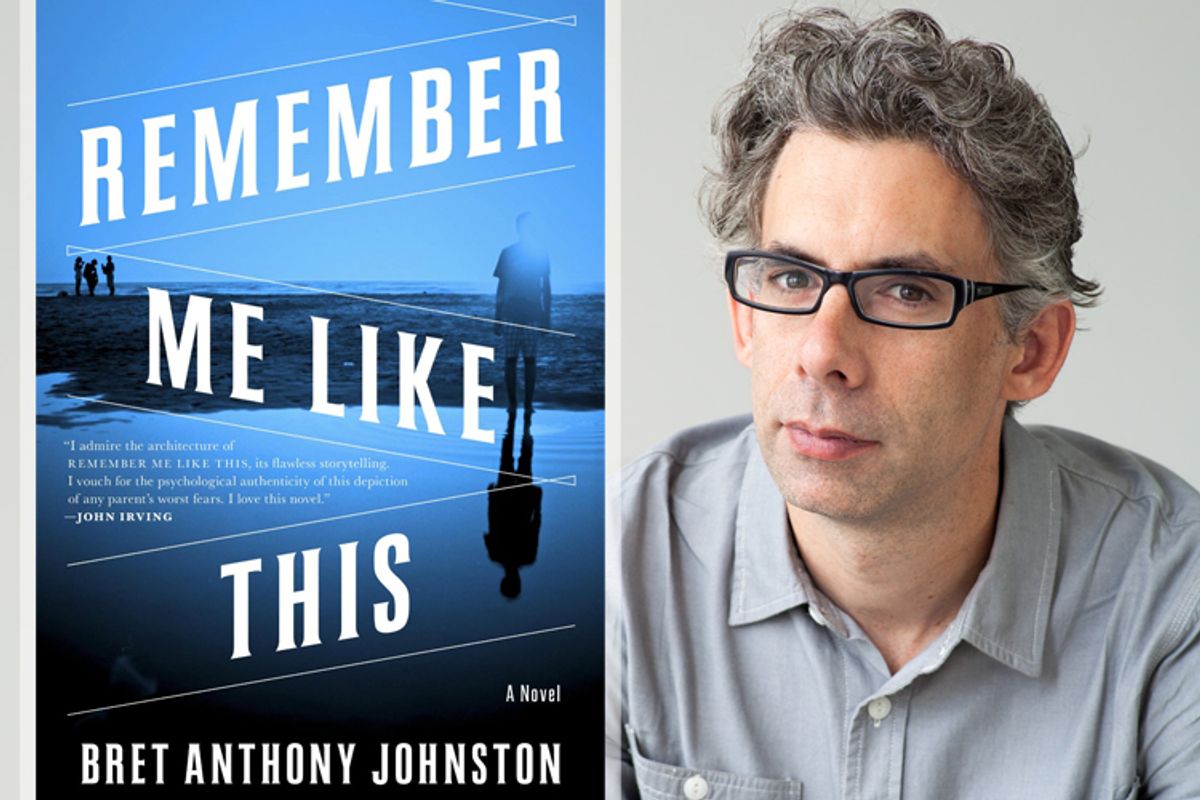

Bret Anthony Johnston is the author of "Corpus Christi: Stories" and the editor of "Naming the World and Other Exercises for the Creative Writer." His work has appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Best American Sports Writing and The Best American Short Stories. He teaches at Harvard University, where he is the director of creative writing.

"Remember Me Like This," his debut novel, focuses on the Campbell family after Justin, the oldest, is abducted. It has already received raves from Andre Dubus III, Alice Sebold and Jill McCorkle, who described it as a “brilliantly rendered portrait of a family in the aftermath of trauma.” John Irving praised its “flawless storytelling,” and goes on to say: “It is as a father of three sons that I vouch for the psychological authenticity of this depiction of any parent’s worst fears. Emotionally, I am with this family as they try to move ahead — embracing ‘the half-known and desperate history’ that they share. I love this novel."

So do I. "Remember Me Like This" is breathtaking. Deeply empathetic and masterfully constructed, it’s a raw, courageous portrait of a family attempting to rebuild themselves. It’s a novel that has both the feel of a great epic and the focused intensity of standing on a highwire. I read in awe. Over the course of a few weeks, I had the privilege of corresponding with Bret over email to ask him more about his debut novel.

This novel completely subverted my expectations, in the best of ways: the surprise for the reader is that Justin, the son, returns home safely — in fact, quite early on in the book. I was hoping you could talk a bit about how you came about this. Did you always know that he was going to be found early on in your story? Or was it something you came upon later?

Thanks, Paul. I always knew he would be found early in the book, and I always knew he’d have spent his so-called “away life” very near his family, but that’s about all I knew. I didn’t know where he’d been for those years or who’d been with him. I didn’t know how or why he’d disappeared. I had no idea how the Campbells would react to his return, or how Justin would. I was deeply curious about what those months would look and feel like after such a traumatic ordeal, and in many ways I wrote the novel to satisfy my curiosity.

The relatively short trajectory — those few months — brings so much intensity into the story. Every action and thought and passing day feels so heightened. Not to give too much away, but the novel opens with a dead body. Then it grabs you by the throat and retraces the steps leading to that moment. How did this novel start for you? Can you pinpoint a particular seed from which it grew, whether it was something you read or heard about?

There were two distinct starting points in my imagination, and it’s when the tracks converged that I knew I had an idea for a novel that would sustain the years of work the book would take. The first one happened years ago, almost decades, when I was still living in Texas. I volunteered to help rehabilitate a dolphin that had beached itself, which is what Laura Campbell does in the book. The rescue coordinator regularly stressed how difficult it was to get volunteers for the overnight shifts, but every time I tried to sign up for those, the slots were always full. I could never get to the sign-up sheets in time. For years, I wondered who was taking those shifts that were notoriously difficult to fill, and after I moved out of Texas, I found myself imagining that specific volunteer. Someone with insomnia, someone who wanted to keep a low profile, someone who didn’t want others to know she was volunteering. Piece by piece, the image of a married woman signing up for the shifts under her maiden name emerged. Still, I didn’t know why she couldn’t sleep.

Then, we started to see footage of soldiers coming home from the war and surprising their families. I have mixed feelings about this footage, but I can’t deny how struck I was by those moments when you see the shock give way to recognition on the family members’ faces when they see that their soldier has come home safe. I didn’t want to write a war novel, but I couldn’t shake my curiosity about what it would feel like to see a loved one for the first time after a long and painful absence. Then I realized what was keeping my dolphin volunteer up: her son was missing. She was volunteering to save the dolphin because she hadn’t been able to save him. That’s when I understood that Justin was alive, when I understood there was a novel waiting to be written.

I love how a character was born out of this moment of convergence. Normally, while reading a book, I feel like there’s a period when I’m getting used to the characters, getting to know them and their point of view. What struck me immediately as I began this book was that I didn’t experience that “breaking in” period. One of the book’s greatest achievements, for me, is how fully formed these characters are from the first page. I’d love to hear a bit about your writing process. Did these characters live inside your head for a while before you began to write the story down? Or were you sketching them out in some way? How did they live before they became who they are in this book?

As I mentioned, I’d been thinking about Laura Campbell in large and small ways for years, wondering who she was. The other characters, though, emerged as the novel unfolded. They were born from the daily labor and countless mistakes. Draft after draft, I worked to render people who were complex and vulnerable, wounded and exhausted, hopeful and loving and angry. I hope I’ve done my job. For me, the trick is to surrender to the characters and follow their lead. I try one thing after another, hoping they’ll quicken and come to life. I want them to surprise me by doing what I would never do, and I want to exact as much pressure on them to find out who they are in their very essence. My aim is not for the reader to see the characters being built throughout the novel, but to see them being revealed. If folks are kind enough to read my fiction, I don’t want to burden them with seeing me build a character from the ground up. That feels akin to inviting someone to stay in my house that lacks the walls and roof. I want the revelations to be so complete that by the end the readers knows the characters better than they know themselves.

I love that this novel purposefully, masterfully avoids sensation. We never discover why Justin was abducted or even learn that much about the abductor; the manic chaos of a search and an investigation happen off-stage; we’re not even entirely sure what happened to Justin while he was held captive. All this is left in the responsibility of our imagination. What was that like for you as a writer? Was it ultimately freeing to avoid the expected? Or more difficult? I found it an extraordinary way to focus entirely on the characters while having this backdrop that borders on a psychological thriller.

Something I’m learning about myself as a writer is that I’m interested in aftermath. I’m fascinated by what happens after a storm passes, the stories that are left in the rubble, what people will try to salvage, what they’ll abandon. So I just wasn’t interested in the questions of what happened and why and how, and as I understood Justin more deeply, I knew he wasn’t interested in them either. The answers are in the novel, but they’re not dwelled upon. We’ve read that story before, so I didn’t see much of an opportunity for discovery. I wrote in the opposite direction of what I knew, in the opposite direction of what I suspected the readers had confronted before. This approach made for a more difficult writing experience, but I think it also made for a more interesting and rewarding one. I hope the same proves true for the readers.

It’s a book that’s hard to put down. I think part of what hooks us is that we desperately want that whole picture. We keep turning the page for it. We sense something is horribly wrong, that each person is processing what they have gone through so differently, and yet they are all connected by this slow burn within them. A burn that has some serious consequences by the end of the novel. How difficult was it to keep that burn, so to speak, just below the surface until the end?

Thanks, man. One of the things that I wanted to do with the novel, maybe the only thing I wanted to do beyond empathizing with the characters, was to write a story that compels the reader. Plot gets a bum rap in literature — there’s a sense that it’s a pedestrian concern, an interest that should be outgrown — but the ideas of causality and consequence are wholly interesting to me. I love fiction where something happens, where a character’s desire becomes, through a strange alchemy, the reader’s desire. I wanted to write a novel that made the characters and readers want something, but also made them wait for it.

There’s a moment for me, after Justin is found, where we see that something is wrong with his leg. It’s subtle, the way you bring it up, but I had to pause there and take a breath. The family experiences a “happy ending” but a lot of darkness haunts the pages. Did that ever affect you emotionally? Were there times when it was difficult to stay in the world?

This was a very hard book to write, no question. I did a lot of research, which was equally difficult, and there were certainly times when I felt overwhelmed. Reading about missing children, about the toll it takes on their families, about the psychology of the abductors, even about sick dolphins—it could feel like too much. A couple of times I retreated and took what Flannery O’Connor called “vacations from the novel” and wrote stories, but mostly I tried to stay in the world and more fully identify with the characters. I would remind myself that they weren’t getting a break from it, so why should I? I felt responsible to them and responsible for them. By the time the novel was finished, I felt changed by the material.

We’re also dealing with multiple points of view in this novel: you have the father’s perspective, the mother’s, the grandfather’s, and the youngest child. It’s a brilliant chorus of secrets and heartbreak, misunderstandings and always, always that desire to connect. Was having multiple perspectives always the plan? Was there one character you started with?

Laura Campbell, the mother, was definitely where the book started, and the more I came to know her, the more I understood her family. I knew she would need another child to stay alive; if it weren’t for Griff, I think she would have come untethered long before the novel began. Whether she would have committed suicide or just exiled herself as a kind of penance, I don’t know. I just felt sure that we’d lose her without a second son. And early on, I understood that Griff would have assumed a kind of caretaking role with his parents, that he would constantly be working to save them, to spare them further pain. The interesting thing is that most readers have so far assumed that the character I most identify with is Griff. It makes sense, not least because of how much he loves skateboarding, but in reality the character who most resembles me is Cecil. In my heart, I’m a sixty-seven year-old pawnbroker with a pistol under the seat of my truck.

So, I don’t know that multiple perspectives were part of the original plan, or if the characters just kept insinuating themselves. I understood that they would look at the same thing — such as Justin’s limp or the postcard from California — but what each of them saw would be drastically different. They had all lost Justin, but he was a different person for each of them. The discrepancies in their perspectives felt revelatory to me. It felt like the story itself, so I worked to excavate how the characters saw the world and how the variations in those visions would open up the story.

And how did you keep track of them? I read the novel as a variation on grief: how this family copes with a sudden abyss in their lives. Then, quite suddenly, that abyss is filled. Except no one’s sure how to be a family again. There’s so much unspoken between everybody. So much held in. At times they need to look for answers elsewhere; and they forget about what’s in front of them, almost losing each other. Their journeys are incredible to witness, the way they crisscross and separate. It’s so seamless on the page but I imagine there were days when it was difficult to juggle them.

An idea that feels central to the book is that even after an abyss is filled, the abyss is still there.

As for the practical aspects of the daily writing, I had a huge bulletin board in my office and I would keep track of what had happened or appeared in each chapter. The notes were color-coded for each POV, so I could take in the book in a holistic way, seeing that we needed more or less of certain characters based on what color ink was missing from a certain section. For all of my jabbering about empathy and surprise and discovery in writing — things that I believe in with my whole heart — I’m also a very pragmatic writer. I’m very blue collar about this vocation. I show up for work each day with specific jobs that need to be completed and I don’t clock out until they’re done. The bulletin board was kind of like an evolving blueprint. I could see where the electrical needed work, where the drywall needed hanging, where the foundation was still drying.

Do you have a particular favorite character in the novel?

I don’t know if I have a favorite, but I know the characters I enjoyed writing the most were Cecil and Fiona. Cecil felt familiar to me, as I’ve mentioned, and that familiarity was a constant and welcome surprise. For my money, though, Fiona is the strongest and healthiest character in the book. She’s honest and compassionate, independent and intelligent, and she’s far more mature and responsible than anyone would expect. I think she loves the Campbells in a pure and unconditional way, and I think she sees them as their ideal selves, not in spite of their wounds and losses, but through them. The short scene with her and Cecil at the end of the book is, without question, one of my favorites. Without realizing it, I’d been waiting for them to spend time with each other. I’m very glad they finally did.

Cecil feels the most in control. He’s the stabilizer in the family, I think. And yet by the end he’s the one that steps over the line, the one that confronts the family’s demons head-on. Without giving too much away, I was wondering if you could talk a bit more about him. He’s the one who seems to have access to everybody. He can be with his son or his daughter in-law or grandchildren. He’s the one that can cross the bridge and confront Justin’s missing years.

As I mentioned, he’s the character with whom I most identify, but not in these admirable ways. He’s private and methodical, traits that can be as frustrating as they are comforting, depending on the situation. It’s not true to say that he’s less affected by what’s happened to Justin, but he does a better job of keeping it to himself than the other characters. Such behavior isn’t healthy, but I can relate to his stoicism.

That said, in earlier drafts of the novel, Cecil was more aggressive and prone to violence. He could be belligerent, if not outrightly cruel, and it took considerable work to restrain him. The scenes worked well enough, but I never believe Cecil would make a scene if he didn’t have to. He takes the long view on things, and the previous incarnations of the character was short-sighted. As for the ending, I can also say that the way events play out was a complete surprise. I’d always imagined that the novel would end differently, and I’d always imagined Cecil in the thick of it. I suspect he did too.

Animals are a recurring theme in the book. I might even go so far as to say the book has two spirit animals: the dolphin that Laura cares for and the snake that Justin cares for. Just to go back to an earlier thread in this conversation, could you talk a bit more about why you chose those animals in particular? And why these two characters in particular? And what meaning the animals hold for each of them?

One of the things that I’m constantly working against in my fiction is including too many animals. If I thought I could get away with putting a camel or walrus in the book, I would have. In fact, I think I had something about both of those animals in an early draft and I edited them out.

With the dolphin and snake, though, those are animals that are common to South Texas. Readers have seen them as symbols—the connection between a mother dolphin and her calf, and the fact that a snake is always seeking warmth—and I respect and appreciate those considerations. For me, though, the most important thing about them is what you’ve kindly mentioned: that both Justin and Laura care for animals as a way of caring for themselves, as a way of reaching for each other. They share a bond, and while I’m not sure they recognize it, I do. I hope the readers do too.

Did you have any pets growing up? Or a particular animal you felt attached to? I feel like the more I read your work, the more the animals in them shine.

See? It’s a problem.

I’ve never met an animal I didn’t love, and I’ve spent time with a lot of them in my life. It’s one of my greatest joys. I grew up with plenty of dogs and cats, but also with horses and birds and snakes. I read about animals constantly, and I can’t pass a dog on the street without trying to pet it. A few summers back, I went to a writers’ conference and caught a snake on a trail. Understandably, the snake didn’t want to be caught and as such, it bit me. The bite broke the skin and when I was walking back to the conference, I passed two of the directors and they asked why I was bleeding. When I told them, they kind of freaked out and looked like they’d vomit. They were worried about me, but nothing could’ve made me happier at the conference.

The Corpus Christi area in Texas has become your Yoknapatawpha County. Has this always been something intentional or did it come about almost by accident? I ask because I wonder if we really have any choice in the places that draw us in as writers. Whether we end up circling back to certain places, always.

It was by complete accident. I never wrote about Texas while I was living there, and now that I’ve lived outside of the state for almost two decades, the story ideas keep offering themselves up. I can see the area more clearly from this far away, and what I can see fascinates me, stokes my imagination in ways that other places so far haven’t. I’m interested, both as a reader and a writer, in stories that could happen in only one place, wherever that place is. For me, the setting forms and informs the characters. The context—that is, the place—creates the content.

Do you think you’ll always write about Corpus in some way?

I don’t think so, though my track record would suggest otherwise. That said, if everything I write were to take place in South Texas, I’d feel no compunction about it. In fact, I feel grateful that the landscape and its people continue to yield stories. I don’t feel beholden to the area, I don’t feel as though my life’s work is to give voice to that part of the country, but rather I feel fortunate and humbled that readers have so far shared my interests.

This is your debut novel. What was it like to go from writing short stories to writing a nearly 400-page epic? Or were you working on this book while you were writing your story collection? Can you talk a little bit about the differences between the two?

I think writing is the probably the hardest thing anyone will choose to do, but I don’t think writing a novel is any more difficult than writing a short story. They’re both unimaginably difficult, and you have to relearn everything with each new project, if not each new sentence, but I don’t think one form is harder than the other. A novel just takes longer. The trick is to find material that will sustain and reward the time, energy, and emotion that you’re going to afford it. Will your curiosity about this moment in these characters’ lives last for two years? For three or five or ten? If your curiosity doesn’t have the necessary depth and breadth, you’ll come up short. Of course, the same is true for a short story, but those are easier to throw away.

So making the jump from the short to long form wasn’t difficult, but I also didn’t take it lightly. I waited until I had an idea that felt solid enough to hold the weight I’d exert on it throughout the writing process. From there, I approached writing the novel the same way I approach writing stories. I work every day for a set number of hours, usually at the same time, and I never reread or rewrite anything until I’ve reached the end of the first draft. The first draft was really long and unnecessarily complicated — too much happened in each chapter — and the second draft was considerably shorter. I don’t know how many drafts I went through, but the process felt identical to writing stories. It just lasted a lot longer. You have to be patient. You have to surrender any hope of quick or easy gratification. You have to trust your craft and characters more than you trust yourself.

How long did it take to finish the novel?

Five or six years, I think? Maybe seven. I don’t know. I’m a slow writer, but I also didn’t feel the need to rush. Kendra Harpster, my editor, is a genius and saint. As is Julie Barer, my agent. They allowed me to take my time, and any success the book finds is because of their confidence in my slow-ass process. Without them, the book doesn’t exist.

Is it strange to let a book go? Does it feel like letting go?

It’s strange that anyone would care to read the thing. I mean this very sincerely: My mind reels at the thought that anyone would be interested in reading something I’ve written, let alone something that takes place in a made-up town in South Texas. Occasionally I’ll hear writers complaining about how they can’t believe their sales weren’t higher or how they got passed over for this or that, and I’m always shocked to have any readership at all. I’m not being falsely modest here. I worked my tail off on this book, and I’m proud of it in certain ways, but that has nothing to do with anyone else feeling moved to crack the spine. It doesn’t feel strange to let the book go. It feels beyond strange that anyone would want to pick it up.

Were there particular books that inspired you? Or any other art forms?

Most everything I’ve written is, I think, an attempt to come close to PJ Harvey’s album "To Bring You My Love." I’m proud to fail every time. At least with this one, I used her lyrics as the epigraph. I’m getting closer.

Shares