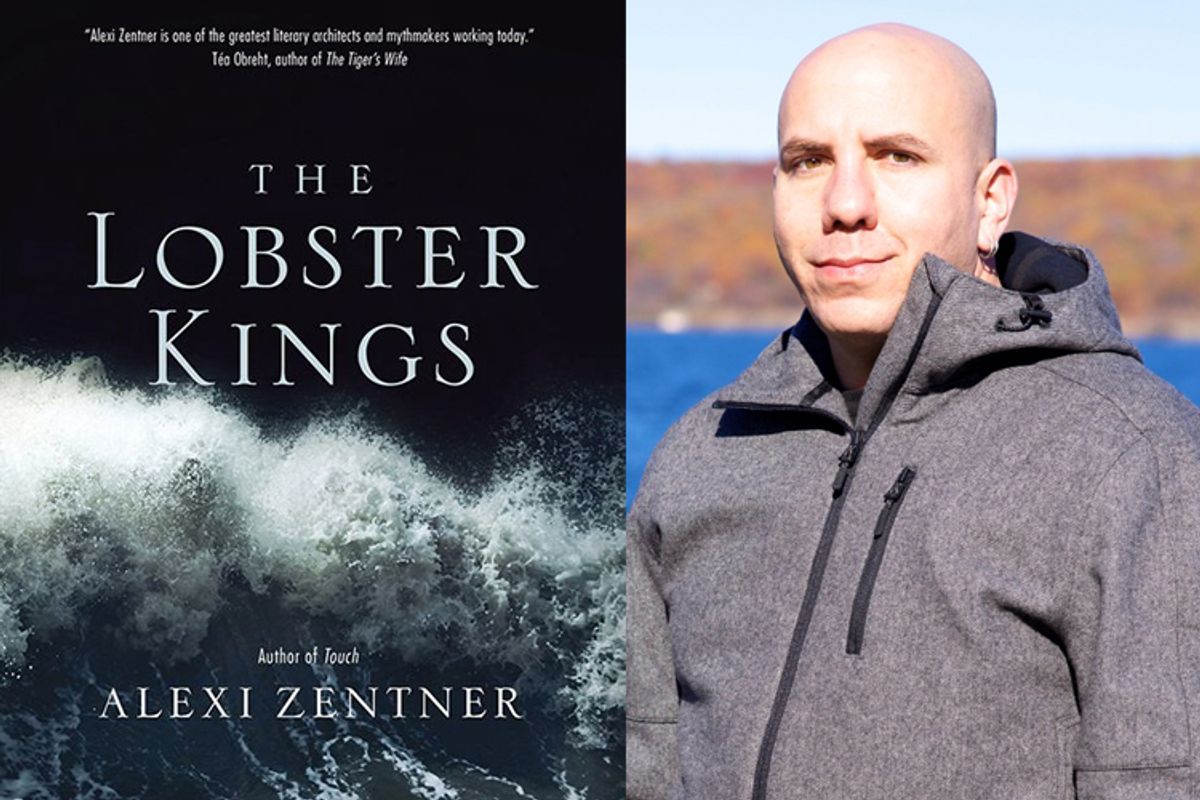

Alexi Zentner's new novel, "The Lobster Kings," is set in a lobster fishing village and focuses on Cordelia Kings. Inspired by "King Lear," Zentner's second novel is the story of Cordelia’s struggle to maintain her island’s way of life in the face of danger from offshore and the rich, looming, mythical legacy of her family’s namesake.

"The Lobster Kings" has already been getting raves from Ben Fountain, Stewart O’Nan and the Toronto Star, which said “Zentner displays more talent and controlled craftsmanship in 'The Lobster Kings' than many other writers will manage in a career’s worth of novels.”

Alexi and Téa Obreht ("The Tiger's Wife") met recently to talk about "The Lobster Kings'" inspiration and influence, Shakespeare, writing outside your voice, and the way myth and magic work in fiction.

Alexi Zentner: We just celebrated Shakespeare’s 450th birthday, and "The Lobster Kings" riffs on "King Lear," so let me start by throwing out the idea that all literature is in conversation with all of the literature that came before it. While Shakespeare wasn’t the first voice in the room, in North America and Europe, he’s one of the loudest voices. Is that something that resonates with you?

Téa Obreht: When you’re talking about Shakespeare, every writer and reader that you come in contact with has been influenced by Shakespeare. If not directly, then certainly by the way he lays out his plots and the way that he steals myths and restructures them. What I’ve realized over the last couple of years is that even literature that you aren’t aware of and that you haven’t read influences you, because it influences so many other people and so many things that you’ve read. It’s like bio-accumulation. You get the most of it because you’re the end of the line. You’re the newest.

And one of the reasons why you’re at a disadvantage if you’re a writer and you aren’t familiar with Shakespeare is because he has influenced so many things, whether you are aware of it or not.

"House of Cards" has a strong undercurrent of "Macbeth," and Kurosawa’s "Ran" is inspired by "Lear." So much of what you tend toward as a reader and a writer is based on what you are exposed to in your early stages in your reading. You have these very clear templates you are exposed to from Shakespeare, and it shapes what you expect.

He’s formed what we think of as storytelling. And one of the things that I think is interesting about our work and we both have in common, is that we are both really interested in the idea of storytelling and how storytelling works and how myth works. For you, one of the books you reference in "The Tiger’s Wife" as a touchstone is "The Jungle Book."

It was one of the first books I remember reading, and while I don’t draw from it for plot, definitely the idea of peopling a narrative with a tremendous number of characters who all have a story and a place in a community — even if in "The Jungle Book" that community is of wild animals — was always fascinating to me. I like the idea of telling a story that is anchored in a far larger narrative that you get a little piece of. What was it for you?

Fairy tales and Greek and Roman and Norse mythology. I read a lot of that when I was a kid. The sort of stories that seem to cut across cultures and time.

And Shakespeare?

And Shakespeare. I liked Shakespeare in high school, but in university I spent a semester studying in London, and it was sort of in the middle of me falling deeply in love with literature, and I took a Shakespeare course with a professor who couldn’t imagine anything more important than Shakespeare. He was going blind — which resonates with King Lear, of course — and he’d committed to memorizing the complete works of Shakespeare, because he couldn’t imagine living without having all of Shakespeare in his grasp. And I remember, when we were studying "Lear," near the end of the play, this moment when Lear comes out with Cordelia’s body in his arms and asks himself, in effect, will I ever see you again, Cordelia? My professor asked the question and read the response, which is, “Never, never, never, never, never!” And his voice rose to a thunder by the third "never," but by the fifth it was barely a whisper, and it was all he could do not to cry, like Cordelia was really in his arms, like it was his own daughter who had died.

Hence the influence of "King Lear" in "The Lobster Kings."

And yet, "The Lobster Kings" isn’t a retelling of "King Lear." It’s a riff. It pays homage to "King Lear." I’m not trying to hide it. The narrator is named Cordelia. But I really didn’t want to retell "King Lear," but rather to try to explore it. Do you feel like you do that in your work? Consciously jump off from something that has come before?

I think we’re always trying to do something new. Or maybe we’re trying to delude ourselves into the idea that we’re doing something new?

Exactly! But do you have to know where you are coming from, what the influence is?

Maybe if we want to talk about influence, we should talk about the fact that there seems to be a lot of conversation in the literary community about this purported return to magical realism. Readers have certainly pointed out influences of it in your work and mine — but I’m also thinking of writers like Karen Russell, Porochista Khakpour.

Well, you know that I’m resistant to the term "magical realism" when it’s applied to my work, and I know that you’re resistant to my resistance to magical realism, but I like to call what I’m doing mythical realism. I think that magical realism is so rooted in specific cultures, and I think what all of us are doing is something new and something different. Magical realism at a slant. But the places you can draw your influences from have widened. As important as Shakespeare is, he’s no longer the only voice from which you can begin your conversation.

For me, a new project always starts with the question, what do I want to talk about? What am I preoccupied with right now? The story comes to life from that. And then about halfway through you realize what the influence was. Did you know right away that you were dealing with "King Lear"?

I started with the idea of Loosewood Island. That rugged landscape, those working fishing communities down east, got under my skin, but once I realized I was preoccupied with the question of fathers and daughters, yeah, I knew I was walking some of the same ground as "King Lear." How about with "The Tiger’s Wife"? Did you know right away?

I can tell you that with the novel I’m writing now, my second novel, it only came to me later on. I was probably a third of the way in before I realized that the framework was that of a western even though it’s set in the Balkans. But once I realized that, it was very freeing, because I had all this source material and precedent to play with. It’s a question of living comfortably within that influence.

If you realize early what your influence is, you can have a better understanding of what you are writing about. Or maybe it’s that when you know what the influence is, you can break out of it?

We all live in a world in which these stories exist. You’re made out of the stories that you’ve heard and seen and loved. It’s freeing to realize that. For "The Tiger’s Wife," it took me a long time to realize, as I was writing it, how tied in it was to those human and animal pact stories, the kinds that are in play in almost every culture. A woman marries some sort of an animal ... And you have that in "The Lobster Kings"!

I hadn’t made that connection, but you’re right. The first of the Kings family to live on Loosewood Island ends up marrying a woman who was a “gift from the sea,” and there’s a part of the novel that explores the idea that she was a selkie, a sort of mythical shape-shifter, a seal in the water but a woman on land. The man has to steal her sealskin coat while she’s in the shape of a woman. And if the woman falls in love with the man, the tragedy is that she can only come ashore every seven years, and even then only for a short time. There are other myths in the book, and when you say that we are trying to do something new, that’s why we take bits and pieces of the myths and then build our own worlds around them. Maybe it goes back to this idea that if literature is in conversation, we aren’t trying to just memorize the words and parrot them back, but are rather trying to further the conversation.

What was your way into "The Lobster Kings"?

I’m the father of two daughters, and what was interesting to me about "King Lear" was less the question of giving away a kingdom, but rather what it means to try to be worthy of inheriting it. What does it mean to be the daughter who has to take over? The story of trying to live up to the myth is more interesting than the myth itself. Myths are really just stories that get handed down, and I’m interested in the ways in which family myths get started, and how they get retold and reshaped. Where does myth meet the real world? For somebody like Cordelia, who is living with this epic, mythic family story —

And she has to be in conversation with it.

Yes! And for me, as a feminist, as the father of two daughters, one of the things that I am preoccupied with is the question of how you raise girls to be strong women. I’m trying to raise my daughters to be the kind of women who can say, it doesn’t matter to me how it’s been, this is the way it will be.

Did you worry about writing in the first-person female voice?

It’s so funny, because as the book is coming out, I’m getting that question a lot: Why did I choose to write such a strong female voice? And the honest answer is, why not? It never occurred to me not to. The default voice doesn’t have to be male. Why can’t my version of the great American novel, whatever the hell that is, feature a strong woman’s voice?

Which I think — and other readers think — you’ve nailed.

Well, that’s one of those things we’ve talked about. As a fiction writer, if you can’t write outside of your own voice, it’s tough. I didn’t set out to write a woman’s voice. I set out to write Cordelia. There is no base female voice just like there is no base male voice. There are just singular voices. I can’t write women — nobody can — but I can write a singular woman. I can write the shit out of Cordelia.

Your first novel, "Touch," was also a story about family myths, but it came from a very different place. I think that novel was more about myth gathering, about processing the information of coming from a family with an enormous mythology, and "The Lobster Kings" is, in some ways, about how Cordelia can move on from coming from a family with a real mythology. What led to that narrative jump?

I think "Touch" was dealing with the question of how do you process family stories and myths, and "The Lobster Kings" is dealing with the question of how do you make your own family stories and myths, how do you push forward, how do you make your own way. What’s interesting about that question is that we’ve known each other long enough, and knew each other early enough in our writing lives, that we can see the way our work has shifted.

Well, we know it, but maybe people reading this don’t know, we met in graduate school. You threw my 21st birthday party.

And I was already well on my way to going bald when I met you. But I remember reading your first story for workshop and turning to my wife and saying, “holy shit.” I feel like, for both of us, a big part of graduate school was looking at each other and saying, “OK, it’s on. The bar is raised.”

I think it was very important that we both understood that neither one of us had a backup plan. We were determined to be writers.

For me, one of the things I admire most in writers is ambitious writing, trying for greatness, writing outside your own voice.

Writing outside the expected sphere of influence, maybe? Or bringing your own sphere of influence to the table?

Which brings us back to Shakespeare.

Shares