In film, television, theater — and even, lately, the world of sports — the decision to come out of the closet is often less risky, fraught and potentially career-threatening than was once the case. When actor Ellen Page came out earlier this year, for example, her announcement was celebrated for its eloquence and bravery, but was not widely viewed as a controversial story. (Indeed, a story in Time magazine questioning whether Page’s move was even “brave” in the current age garnered far more negative attention than Page ever did.)

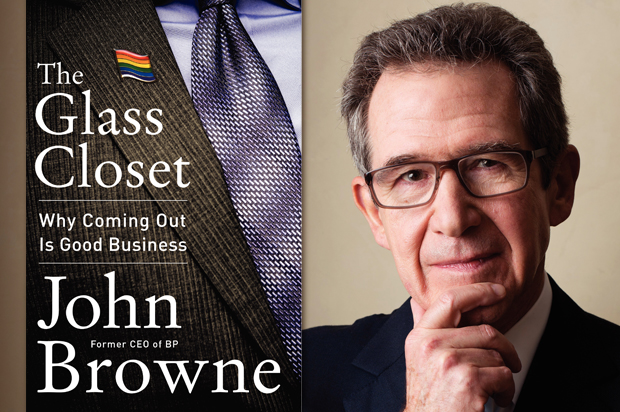

Yet while the entertainment world, often a step ahead of the mainstream when it comes to social issues, has advanced in some ways, the corporate world — even at its highest echelons —remains stubbornly in the past. With his new book, “The Glass Closet: Why Coming Out Is Good Business,” former BP CEO and British Lord John Browne is hoping to change that and jump-start a conversation in boardrooms about LGBT people like the one Sheryl Sandberg’s book, “Lean In,” ignited about women.

Last week, Salon sat down with Browne to talk about his career, his sexuality, the “double life” he once led, and why he believes it’s so important for influential people in business to be open and unapologetic about who they really are. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

OK, so just to start simply, what made you want to write this book?

I wanted to stop anyone from getting to the same position as I’d gotten into. Running two lives that were very separate. A public life and a private life, keeping sexuality private, when it’s impossible to keep them apart, and they collided with a very big explosion in my case. So that was my first and principal reason. My other two are rather more important. Second, is to give people a sense of role models, people who had come out in the business, both well and not so well, to keep it authentic, to give people a chance to identify with people like themselves so that they could gain some confidence. And thirdly, a big third, was to write a letter to, primarily, the straight people of the world, the vast majority, in particular CEOs, to say, this has to be gotten right, you have to set the right tone, leaders make a difference. You have to say I want inclusion, particularly of LGBT people, I want to make it a success, I want my companies to be safe places for people to come out.

What was the “big explosion” that happened in your life that you don’t want other people to go through?

I lived a double life. One was my public life, the other was a life where I dipped in and out of gay society. I knew I was gay from a very early age, but I wasn’t prepared to admit it to anybody, and I suppose it was because of the generation I come from, but also from my background; my mother was an Auschwitz survivor and she had particular views of things. First she said, “A secret is something you keep to yourself, and if you tell somebody, they’re going to use it against you.” And secondly, “Remember, all minorities are persecuted when the going gets tough.” And she said, “Just remember that.” So I interpreted all that [as] in other words: “Don’t show any sign you’re gay, because they’ll think it’s weakness.” Perhaps even I thought it was a weakness at the time …

Did she know that you were gay when she told you that?

We never talked about it, but she was a woman of the world; of course she knew I was gay. But she didn’t want to talk about it. She did not want to talk about it.

So what happened that made you decide the “double life” you’d been leading was unsustainable?

I didn’t actually stop; I was stopped. What happened was, I met a guy on an escort website, and it converted into a sort of relationship, which I stopped eventually … Then he decided — he sent me some emails that might’ve been tantamount to a threat; I didn’t take them that way — but within a couple weeks of receiving them, he sold the story … about me to the British tabloid press. And then I tried to stop the publication of that, sent a super-injunction. I did a letter, a fake letter — I told a lie about how we met — because we had a cover story anyway, and I continued that cover story. I then immediately apologized but I spent four months trying to fight an injunction to keep it private, and I failed and so I was outed …

How did you feel when that happened, when you were outed? Was there any relief over no longer having to live a double life?

In the moment, I was probably reasonably numb, I would say. I’d spent four months fighting this publication, during which I couldn’t tell anybody what was going on … And I had to pretend that nothing was happening, everything was fine … I kept it all to myself until they realized everything … [A]nother form of [my] double life [was] demonstrating all is fine to the world, and keeping this to myself. So when it came out, I was exhausted. I think, in retrospect, it’s the best thing that ever happened to me … I’m much more relieved. I’ve got my own voice, and I feel much better than I did when I was tied up with double lives.

Now, you said the second reason you wanted to write this book was to provide people with —

Role models. When people want to change or to do something, it’s a very natural thing to search for people like themselves who’ve been in not dissimilar situations, and say, “Maybe I can learn something from them.” Role models perform that function. So the question is, are there role models [for LGBTQ businessmen and women]? And I said, “I think in this book I want to have stories of people,” so I interviewed a lot, about a hundred people (some of them got in the book, some didn’t). Many of them are on my website, glasscloset.org, which is about people adding stories and sharing them, because this is about getting confidence. There’s always a feeling, I think, when you’re isolating yourself with a double life, you do feel “no one’s quite like me,” and that’s actually just not true. So having the role models is very important. You don’t have a lot of role models at the highest corporate levels. If you look at the 700 biggest companies on the S&P index, there isn’t one led by an out gay CEO [and] that’s probably statistically improbable, I would say. There’s probably someone who’s LGBT there, but the fact is they’re not out. The fact is, I think people sense that corporate life is, frankly, conservative life, and they don’t want to come out because they think it might affect their career prospects, it might upset their clients, it might give people an advantage over them because they might be somehow bullied. I think that that sort of thinking we’ve got to get rid of …

But what made you decide that you wanted to be a role model for other people? It can be quite a sacrifice or even a burden, being a trailblazer for social change. Why do you say that?

Because I think people do relate … [In business,] if you do reserve yourself, then you’ve reserved part of you, and people aren’t quite sure about you, I think. When you embrace [your own identity] … I think everyone’s more relaxed, they get on, they work better, productivity goes up, everything improves. There’s a story in the book about a woman, a lesbian defense contractor in the U.S. She used to work for a big defense contractor. She came out, and she talked to her straight colleagues and said, “I want you to imagine the following feeling: Go back to your office, take down all the photographs of your family, take off your wedding ring, don’t talk about what you did at the weekend, and if asked about your family, change the preposition, change the subject the whole time, and tell me how you think that feels.” That’s a good illustration in a story form of the problem. Because people do bring their whole selves to work — straight people do. Absolutely, they do … Go around to the CEO’s office — what do you see photographs of? Family. But if you’re in the closet, what do you see? Photographs of your house, maybe your dog. But not, I think, of your partner …

People need to get used to [LGBT people having their own family pictures]. That’s why it’s really important that CEOs set the right tone. They really have to push on to say, “I want a place where it’s safe for people to come out, where we respect and value it, and the playing field is genuinely level, and we include everybody.” … It’s tough enough with just gender. But in gender, it’s … there’s no undisclosed identity. Whereas with LGBT, there’s an undisclosed identity, and that’s the difference. So, what I want to see is a safe place to work, a safe place to come out, and a place where people think it’s just part of their ordinary landscape.

So, coming back to our original question … why am I doing this? … I do feel that when I review [my career], it’s a great regret that I didn’t come out. I think it’s something that I should try and make up for, for lost time.

What’s the book’s reception been so far — both within the corporate world and the global LGBTQ community?

It’s too early to tell. Certainly in the U.K., where this launched two weeks ago, I’ve got some good feedback from both communities. Naturally, there’s critical feedback as well. People from their point of view are saying, “Well, it’s all right for him because he’s towards the end of his career.” (I’d like to think I’m not, but I’m older than the average.) So they say, “It’s all right for him; he can talk like that.” That’s partly true, but I think then I want to reverse it and say, “But the learning I’ve got may be of relevance to others.” So the question is: How generously do you want to listen? I think a lot of CEOs, certainly the ones I’ve talked about, say, “Yes, I want to do more in this area.” Some have done a very good job in this area. But there’s still plenty more to do.

But do you ever worry that talk like that, expressing a desire to “do more,” might be little more than lip service?

That’s why what this cannot be is doing more by employing yet another person in the H.R. department. The H.R. department is very important, but doing more really is sending the right signals and actually doing something about it yourself. This is true of when we want to make a big change in almost anything, but in these areas … the only person that will be able to move things at all is the CEO. That’s the only person who can do it because everyone looks up and says, “What is she or he really thinking?” It’s easy to comply with process [and offer] lip service; checkboxes [are] very easy. But actually to do what the tone of the top wants you to do is very hard …

So if you were a CEO still today (or advising one), what would you do to change the culture and send a signal that you’re serious about inclusion?

First thing I probably would do in today’s environment is … come out myself. I think I’d have to explain to the board that I’m doing this to be myself, not to draw attention to myself, though that might be a consequence of it. You can actually put that away quickly, and you set a very different tone. Secondly, I would describe why I don’t think that [my coming out] would reduce the business prospects of the firm. But if it did, then I’d have to question whether those business prospects were worth having. If they’re simply based on not dealing with gay people, then do you really want to have that sort of business? … I think even in some of the more hostile parts overseas … [my being gay] would not be used as a reason not to do business … If they choose it as a reason, there’s almost certainly a second reason …

I would talk about making business safe to come out and making sure that selection, promotion, that this particular aspect of diversity is not a barrier … And I would ask for proof from time to time. Hopefully not regularly, but irregularly (that’s usually the best way of getting the proof, is not to routinize it). I’d irregularly get proof that what I was asking for was actually happening … Finally, if I were an overseas operator, I’d want to make sure that people hopefully had come out. And then, if they were posted to Uganda, let’s say, or some difficult place, I’d want to understand the dialogue that was taking place. Whether the … corporation had said, “We do understand the risks. You can go. We support you going. But you’ve got to do things slightly differently because it’s illegal to take any homosexual act anywhere. You have to abide by the rule but … we’ll support you.” So I’d like to see that happen rather than saying, “Oh, I don’t think gay people can go there.” That’s not what I’m going to do on the subject.

This is quite a hypothetical question, but what do you think the reception to the book would’ve been had you written it, say, 10 years ago?

That’s so hypothetical because I was in the closet [10 years ago], so there was no way I would write the book … Let me answer your question this way, which I think is more concrete: I do think the environment has changed. There is no doubt. You look, for example, at politics. A cynic may say, “OK, a gay politicians, an LGBT politician, has to come out … because if they’re discovered, they’d be destroyed.” But actually, they are coming out very rapidly, easily; and they are setting a tone …

Two things to think about: One is, when things are moving forward, constant vigilance is needed just in case they move backwards. Secondly, things need to be accelerated by pushing … I think if nothing’s happening, you can’t really accelerate it with a bomb because the bomb may just go off — the bomb of the book may just go off and people ignore it. Here, if things are moving, I think you can begin to accelerate it by giving it a push. I hope the book will do that in a number of places.

In terms of high-profile people coming out, I wanted to ask you how you felt about Apple CEO Tim Cook, whose sexuality is treated a bit as an open secret, and how the media and activists treat him.

Well, I don’t agree with people being outed. It is a personal decision they have to get. Whether [Cook’s] gay or not — I don’t know whether he is, and I don’t want to comment on him in that way. But whoever he is, whoever they are, I think people should decide to come out [on their own].

Have activists for the LGBT cause pushed back on you at all on that point?

Pushed me on which point?

Outing people.

Yes, and I don’t agree with it. I really don’t agree. I mean, I was outed. And while I think, in retrospect, it was a great thing for me to be outed, I don’t think it’s right. I just don’t think it’s right.

Do you think it’s not right in the sense of being immoral or in the sense of being politically counterproductive or both?

I just think it’s denying human choice, and it is taking away rights. Much as I think suppressing rights is bad … taking away rights by saying, “Well, I don’t care what you think, I’m just going to [out] you” is not an appropriate or civilized way of behaving.