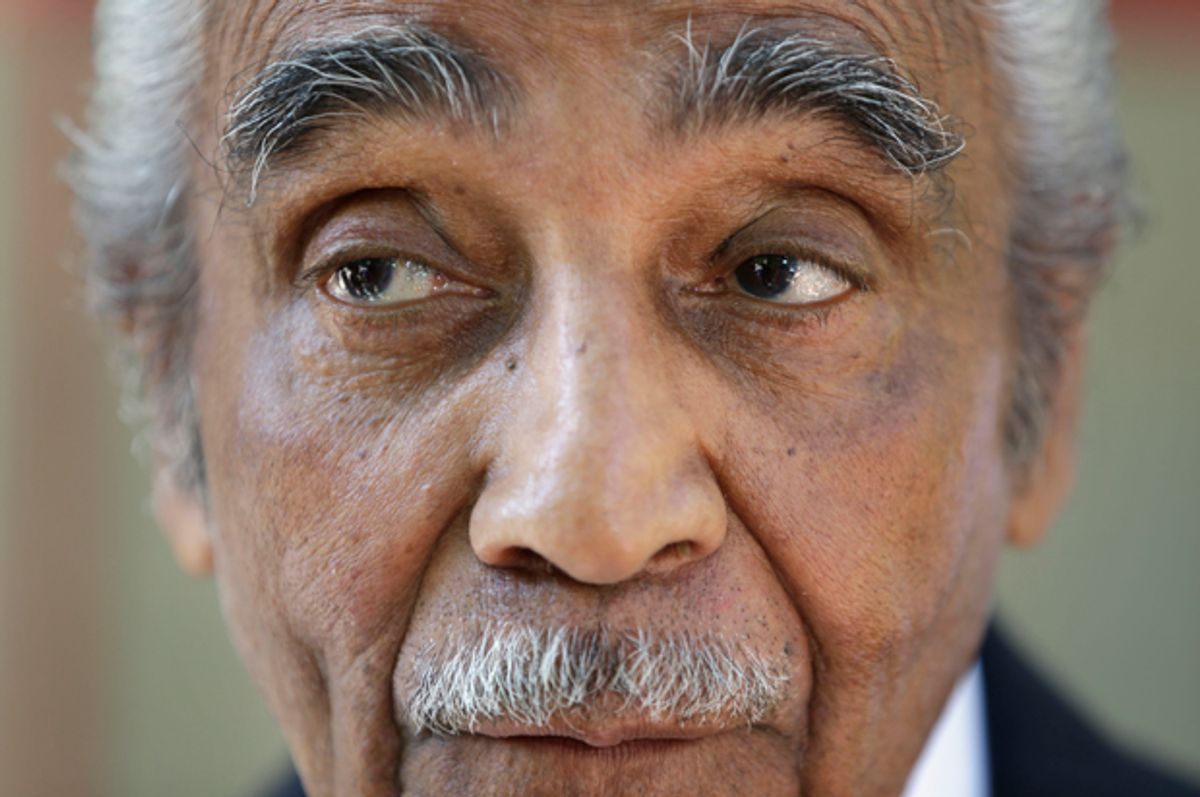

Excitement over Charles B. Rangel’s win on Tuesday night must be gratifying for those who wished to see him in office for a final victory lap through the halls of Congress. But for a community that has changed rapidly without support from many of the leaders who stood with Rangel on stage last night, another term in office must be maddening.

Even hobbled, Rangel is a compelling figure -- and Harlem’s history, politics and culture manifests in his leadership. But given rapid gentrification, the influx of diverse Latino and African populations and the expansion of the district to include the Bronx, there is an incongruity to his continued representation that portends a long-overdue transition in leadership, which was only prolonged by Tuesday’s results.

More than four decades ago, Rangel famously beat Adam Clayton Powell Jr., to become, and remain, the second African American to represent Harlem in the House of Representatives ever. Their transformational leadership was integral to an often-overlooked northern civil rights movement. But while Powell and Rangel loom large in Democratic politics, their ascendency to power and the large-scale inclusion of black voters into the local Democratic establishment is largely owed to J. Raymond Jones.

Dubbed the Harlem Fox, Jones, a West Indian immigrant from the Virgin Islands, was the first black political boss in New York. Despite the growing political clout of blacks in the Democratic party, Roosevelt and New Deal Democrats were disinclined to fully embrace black electoral power fearing reprisals by southern, mostly Jim-Crow Democrats.

Frustrated, Jones and Democratic bosses realized that Harlem demographics were shifting too dramatically to ignore. Southern blacks, Latinos -- mostly from Puerto Rico -- who settled in East Harlem, and a large West Indian population, constituted a new and influential coalition of Democrats that supported Tammany’s electoral activities. Jones used the levers of political patronage to return the favor by providing jobs and resources to constituents. Jones became a partner at City Hall and a vital link to a Harlem community whose influence expanded exponentially.

Meanwhile, Jones had a tenuous relationship with independent-minded Adam Clayton Powell. He wrote that although he made an “insouciant bow towards the Democratic Party when it suited his purposes [Adam] did not need the Democratic Party; if anything it needed him.” Jones mounted several candidates against Powell’s machine -- including a young upstart named Charles Rangel.

Harlem and Rangel have since been synonymous with Democratic politics. In 1989, Rangel and powerful friends Basil Paterson and Percy Sutton saw their colleague David Dinkins become New York City’s first black mayor. The next year, after leaving prison, Nelson Mandela commanded an audience on the same streets that encircle the Apollo Theatre. In 1992, it was Dinkins at Madison Square Garden during the Democratic National Convention that welcomed future President Bill Clinton. Rangel himself would be credited with bringing First Lady Hillary Clinton to New York. Basil Paterson’s own son David became the Senate Majority Leader, lieutenant governor and later governor of New York State.

But much has changed in a very short time. Dinkins was ousted after one term. Ethics violations and public censure forced Rangel to resign his chairmanship of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee. President Obama, the first African American to win the White House, publicly asked Rangel to “resign with dignity.” In 2009, a political coup in Albany toppled the African-American senate majority leader and weakened Governor Paterson (who took over after Eliot Spitzer resigned, and decided against seeking a full term).

Support for Rangel waned. Usual endorsements were going to his opponents. In 2010 Mayor Bloomberg, who held office as a Republican and then as an Independent crossed party lines to endorse him in 2012 -- but the new mayor, Democrat Bill de Blasio, stayed neutral this year. Even the African-American candidate, Bil Thompson, who ran for mayor against Bloomberg and De Blasio with Rangel’s full support, endorsed against him.

Rangel’s attenuating influence mirrors increasingly diffuse black political power throughout the city. Gentrification in Harlem and elsewhere coupled with an outmigration of blacks shrank neighborhood-based political fiefdoms. The Council of Black Elected Democrats, a once powerful advocacy group, is largely defunct. Policy issues involving charter schools, economic development, housing and commercial development that have put Harlem at the forefront of policy trends are largely debated and resolved in spite of the local leadership, rather than as a result of it. In fact the current mayor did little, by most accounts, to consult experienced black leaders on new hires, violating established political customs.

African American young professionals, sensing an abrogation and decentralization of power and who became active in the age of Obama, have looked elsewhere for their cues on civic engagement. Rev. Al Sharpton, once considered a perennial outsider, has become generous to younger Harlem residents who are less bound to traditional political institutions than their older neighbors. It is Sharpton who is now seen consulting with Obama, Bloomberg or de Blasio on policy agenda items. The universe abhors a void – even a political one.

Rangel and company failed to heed the lessons of J. Raymond Jones decades earlier. In order to survive, you must adapt. Instead of nurturing a new generation of leaders and welcoming Harlem’s burgeoning diversity, many Harlem leaders flogged the new populations for being inauthentic. Despite local Assemblyman Keith Wright’s attempts to support Rangel and the Democratic Party through his stewardship of the county and state Democratic organizations, others have often undermined his work through attacks on potential allies.

Tuesday’s victory should be a poignant and final lesson in shortsightedness by many who, out of fear of change, and unfortunate displays of hubris, kept feeding the Rangel machine so they could continually eat from his plate. The new coalitions attempting to gain political strength through expansion and inclusion will need to wait a bit longer for their roots to adhere. In the meantime, they must remember the lessons of Jones, and others, that power derives from having more voices at the table, not fewer.

Shares