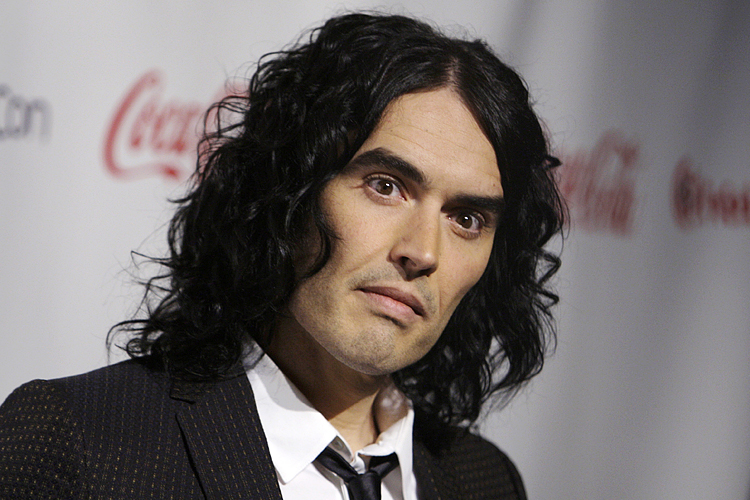

Russell Brand may be the most famous anti-capitalist in the world. He boasts a Twitter following of 7.8 million and regularly performs to sold-out shows, with his signature style of narcissism, self-deprecating humor and leftist platitudes. Brand is just the latest exemplar of a confrontational style of comedy pioneered by Lenny Bruce, in which social structures come under scrutiny, and polemical quips are bandied about – in Brand’s case dealing often with the evils of capitalism.

But here’s the problem: His very critique of capitalism must inevitably succumb to its ideology. And it isn’t a failure on his part, but rather an indictment of the idea that comedy can be a vehicle for radical social criticism at all.

His recent show, “Messiah Complex,” shows the limits of popular radicalism — if it could be called radical at all. Gandhi’s treatment in Brand’s show is particularly revealing. Brand’s critique of Gandhi is the worst of Reddit Atheism — that Gandhi denied his wife, Kasturba, the penicillin that would have easily prevented her bronchitis, yet used penicillin himself a few years later. Brand strips the story of necessary context, like the fact that Kasturba died in 1944, a mere two years after the first patient was ever saved with the use of penicillin. As Rajmohan Gandhi notes in his book on his grandfather, “the drug was untested; injections would be hard for her to bear; her agony should not be increased.” The death of Kasturba should be seen as an unfortunately wrong decision, not as a failure on Gandhi’s part. But by citing this anecdote, Brand shirks a deeper and more complex debate about Gandhi and his work.

In his essay on Gandhi, Orwell begins with the question, “to what extent did he compromise his own principles by entering politics, which of their nature are inseparable from coercion and fraud?” Orwell later questions the idea of nonviolent protest, noting that,

Western pacifists specialize in avoiding awkward questions. In relation to the late war, one question that every pacifist had a clear obligation to answer was: “What about the Jews?” […] it so happens that Gandhi was asked a somewhat similar question in 1938 and that his answer is on record in Mr. Louis Fischer’s “Gandhi and Stalin.” According to Mr. Fischer, Gandhi’s view was that the German Jews ought to commit collective suicide, which “would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler’s violence.” After the war he justified himself: the Jews had been killed anyway, and might as well have died significantly.

A truly radical stand-up comedy performance might consider the implications and uses of violence and nonviolence. It would consider Michael Walzer’s famous “problem of dirty hands,” which occurs when leaders must make political decisions that violate their moral principles (i.e., the use of violence against hostile states, deception in the pursuit of policy). Was Gandhi right to largely ignore the plight of the “untouchables,” refusing to allow them special protection in the parliament? Was his insistence on nonviolence, even in the face of Nazism, a justifiable position?

Christopher Hitchens once wrote, “Gandhi cannot escape culpability for being the only major preacher of appeasement who never changed his mind.” And what of his opposition to birth control and women’s liberation? To truly understand Gandhi and to consider his legacy means mulling over these topics. Instead, Brand critiques a decision of Gandhi that involves his personal, not political life, thereby making his observations purely perfunctory.

There is good reason why Brand doesn’t actually discuss Gandhi — he is performing comedy, not a history lecture. But when he boosts the performance as a show “about Malcolm X, Che Guevara, Gandhi and Jesus Christ and how these figures are significant culturally and how icons are appropriated and used to designate consciousness and meaning, particularly posthumously,” one expects more than a questionable anecdote.

Brand notes that Che was “a little bit homophobic and somewhat ruthless,” but then quickly scuttles the issue saying, “we need only glance at Che to know that that is what a leader should look like.” Brand contrasts a picture of David Cameron with the picture of Che. After a series of jokes about Cameron’s looks, Brand praises Che’s commitment to revolutionary struggle and complains about how Che’s legacy has been co-opted by corporate interests. But Brand fails to acknowledge the cruel irony — that this is exactly what Brand is doing also. Che’s voluminous writings are ignored, and his role in the Cuban Revolution is obscured. Brand merely uses Che as a signifier of his own revolutionary bona fides. He unwittingly reveals his shallow understanding of communism in his defense of it:

Now I know that communism isn’t a very popular idea any more but I looked it up on the internet and it just means sharing. It’s not that bad, we tell children to do it. ‘Share you little cunt.’ People worry, ‘Oh, what about Russia, lack of food lack, of freedom, Gulags.’ They didn’t do it properly! They fucked it up. They didn’t read the manual. They misused it. If someone don’t use it properly, you can’t blame the thing itself, that’s not fair. I’ve mostly use my Ipad for looking at pornography, that’s not Steve Jobs’s fucking fault is it? […] For me, the travesty with Che Guevara is that he’s been reduced to a meaningless icon because of his unconventional appearance, great hair, great beard, his philosophy has been ignored. And that for me is a very great travesty.

The most potent critique of communism is that no one can translate the “manual” — which the architects of communism certainly read — into reality. Brand could have discussed the historical and economic circumstances that gave rise to Stalinism and Maoism or the fact that Marx believed capitalism, not communism should do the dirty work of industrialization, or even concede that the goal of communism is to humanize capitalism. His “defense” of communism is a restatement of its most effective critique. If you asked the staunchest anti-communist why it doesn’t work, they’ll say exactly what Brand does: it’s a nice idea, but you can’t put it into practice. Brand is essentially conceding this point and then again noting what a good idea communism is. Not so radical, after all.

To be fair, Brand is frequently lucid: His discussion of neoliberalism and immigration, wealth inequality and drug use are all good. However, his discussion of Jesus is similarly confused, mixing up the Old and New Testament and ignoring the deeper question (raised by Nietzsche) about Christ’s legacy: It was his decision to eschew social and political change, and instead usher in a kingdom “not of this world.”

The Limits of Stand-Up Comedy

This isn’t to pick on Brand, who is an incredibly funny comedian, but rather to note that the idea of stand-up comedy as a means for radical social criticism is a flawed one. Even the great provocateur Lenny Bruce noted that “the role of a comedian is to make the audience laugh, at a minimum of once every fifteen seconds.”

Such constraints make it nearly impossible for comedians to step outside of already existent narratives and generally accepted premises. Humor relies on mutual understanding, and all comedians ultimately lean upon ideologies already implicitly understood by audience members. To question Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence and the political sacrifices he chose to make would be so far outside of the mainstream consciousness that it would be impossible to generate laughter. Ditto for a deeper understanding of the failure of communism. Comedians like Daniel Tosh who promote rape culture instead of challenging it are not provoking power structures, but cementing them. Brand is an able comedian and has frequently proffered intelligent social criticism.

But the real question is whether he can be both at the same time.

Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert are funny, but the former is an old-fashioned progressive era reformer and the latter pokes fun at a dying ideology. Both do their jobs well, but neither intends to perform deep social analysis or effect political change. This should not be considered a failing, because you can’t fail at something you haven’t tried. John Oliver, free of the constraints of network television, may strive for something more and if he does, create something truly profound. But even then, the pressure to be funny will probably undermine any deep political critique. I argued in the Atlantic earlier this year that comedy comes before politics, which is why partisans don’t make good comedians. It’s also why comedians don’t make good political radicals.

When I talked about these issues with Marc Maron, he told me during a recent phone conversation that he had moved away from his more ideological comedy because:

It’s very tricky, when you’re doing ideological comedy, from a point of view that pre-exists you, it’s very tricky not to carry water for someone else’s agenda. Even if it’s progressive. This isn’t about comedy, it’s about your brain. When you’re immersed, you’re picking a side and whether you know it or not you’re going to honor the talking points of an agenda that it in place, that you become a spokesman for.

This is the crux of the issue: Comedy ultimately relies on some shared understanding, and even the most radical comedians will struggle to push the boundaries. An audience not laughing is a terrifying idea for a comedian to contemplate, and few will risk silence for a devastating idea. Comedians like Stewart Lee who often have minutes of monologue between punch lines often struggle to achieve mainstream success. As the brilliant Bill Hicks would say when audience members heckled him during his monologues, “There are dick jokes on the way.” This is not to say it’s impossible: Robert Newman has a 45-minute act about peak oil.

All of this makes comedians more like gadflies than social reformers. Socrates was far more concerned with personal piety than social change. His refusal to carry out the will of the “Thirty Tyrants” by bringing Leon of Salamis to trial was not a political act, but a personal, moral one. As Stephen B. Smith notes, “Socrates is so concerned with his individual, private moral integrity that … he will not dirty his hands with political life.” Smith compares Socrates to Hegel’s “beautiful soul,” who “values their own private moral incorruptibility above all else.” We see this “beautiful soul” ideology in Brand’s refusal to vote. Socrates’ “Apology” should be read as a plea to allow him to pursue his own moral truth. His invocation of the “Gadfly” metaphor is self-defecatory. He is telling the Polis that he is only like a fly that stings the horse, and is quickly brushed away.

Often, comedy serves the same function. Comedians are gadflies, whose pursuit of individuality and self-understanding will likely sting our consciousness. But the revolution will not be televised. Ultimately, Brand’s dissent is unable to question the deeper assumptions that underlie our society, fails to offer a viable alternative, thereby sacrificing political progress for humorous pedantry. But what “beautiful souls” forget is that their refusal to engage in politics is not neutral. As Howard Zinn notes, “You can’t be neutral on a moving train.”

Comedy is a powerful force. Some comedians can use the medium to forward radical ideas. However, comedy suffers from deep limitations, and only very few comedians in a generation can break through the ideological barriers to forward genuinely revolutionary ideas. For every Carlin, there are thousands of roadshow comedians, and for every genius hundreds run the Letterman circuit telling the same staid jokes.