A few days after the Supreme Court’s disturbing Hobby Lobby decision, the court’s three female justices joined in a fierce dissent on another contraceptive case that underscored the tension and distrust that have split the court, and the country.

At issue was an order by Justice Samuel Alito allowing a Christian college to at least temporarily refuse to participate even in the “accommodation” the Affordable Care Act granted religiously affiliated organizations from the contraception mandate. Such organizations can sign an opt-out form, which then lets the insurer provide contraceptive coverage directly without the employer paying for it. Wheaton College insists that even submitting the form would make it “complicit in the provision of contraceptive coverage.”

On the heels of the Hobby Lobby decision, which seemed to say that the accommodation was a reasonable measure to protect both religious liberty and an employee’s healthcare rights, the order was surprising, to say the least.

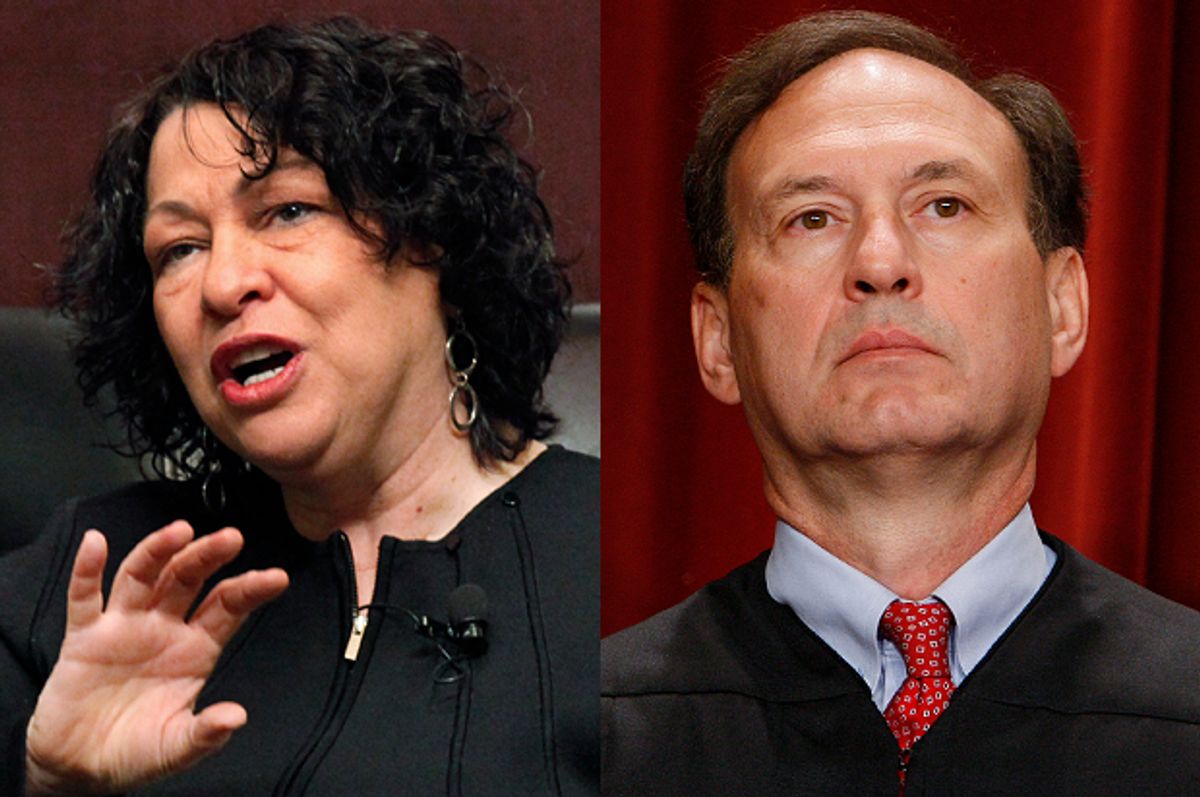

“Those who are bound by our decisions usually believe they can take us at our word,” wrote Justice Sonia Sotomayor in a dissent joined by Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan. “Not so today.”

Now, it’s worth noting that Sotomayor herself granted similar relief in a case involving the Little Sisters of the Poor earlier this year, who likewise claimed that even having to notify the government that it objected to providing contraception violated its religious freedom. In both cases, as Ian Milhiser observes, it’s possible for justices to grant temporarily relief while the groups’ claims make their way through the courts, without supporting the merits of the claims themselves.

So why would Sotomayor sign off on one case and dissent strongly in the latest? Without going into the precise details of each case, it’s reasonable to say that the two look very different pre- and post-Hobby Lobby. In last Monday’s ruling, Alito wrote that the HHS accommodation “does not impinge on the plaintiffs’ religious belief that providing insurance coverage for the contraceptives at issue here violates their religion, and it serves HHS’s stated interests equally well.” The court has held that such temporary relief should be granted only when “the legal rights at issue are indisputably clear,” Sotomayor notes. In the wake of Alito’s Hobby Lobby decision, such rights would seem far from clear.

His Wheaton College decision suggests that Alito, and the court’s conservative majority, is wavering on the issue, Sotomayor wrote:

After expressly relying on the availability of the religious non-profit accommodation to hold that the contraception coverage requirement violates [the Religious Freedom Restoration Act] as applied to closely held for-profit corporations, the Court now, as the dissent in Hobby Lobby feared it might, retreats from that position.

Sotomayor and the SCOTUS minority aren’t the only federal judges worried about the court majority’s vastly expanding the claims of religious liberty permitted by the RFRA. George H.W. Bush appointee Judge Richard George Kopf, of the U.S. District Court of Nebraska, took to his personal blog to blast the Hobby Lobby decision. “The Court is now causing more harm (division) to our democracy than good by deciding hot button cases that the Court has the power to avoid. As the kids says, it is time for the Court to stfu.”

Kopf went on (h/t Think Progress):

In the Hobby Lobby cases, five male Justices of the Supreme Court, who are all members of the Catholic faith and who each were appointed by a President who hailed from the Republican party, decided that a huge corporation, with thousands of employees and gargantuan revenues, was a “person” entitled to assert a religious objection to the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate because that corporation was “closely held” by family members. To the average person, the result looks stupid and smells worse.

To most people, the decision looks stupid ’cause corporations are not persons, all the legal mumbo jumbo notwithstanding. The decision looks misogynist because the majority were all men. It looks partisan because all were appointed by a Republican. The decision looks religiously motivated because each member of the majority belongs to the Catholic church, and that religious organization is opposed to contraception. While “looks” don’t matter to the logic of the law (and I am not saying the Justices are actually motivated by such things), all of us know from experience that appearances matter to the public’s acceptance of the law.

Meanwhile, the disappointing Hobby Lobby ruling has even has some advocates for women questioning the government’s strategy in the case. In “One Big Thing Everyone Is Missing in Hobby Lobby,” the National Journal notes that Alito’s decision didn’t even acknowledge the situation of women who use contraceptives for health issues unrelated to birth control, though Ginsberg’s dissent did. Advocates for ovarian cancer sufferers argue that “the debate was misframed as a contraceptive debate from the beginning,” Lucia Graves wrote. "We've tried to recast that debate to orient the Court to the fact that there's more going on here than pregnancy and contraception, but ultimately the Court went with the way Hobby Lobby had characterized it," attorney Michelle Kisloff told Graves.

It’s true that even Sandra Fluke, trashed as a “slut” and “prostitute” for supporting the contraception coverage mandate, was originally testifying about Georgetown University colleagues who used oral contraceptives to treat health issues. Yet had HHS emphasized the plight of those women, it would have encouraged politicians and judges to sort among the legitimate health and privacy rights of all women. Who would define medically necessary contraception? Would it include women whose health would be seriously damaged by pregnancy? Would mental health count? What about the health of children already born who might require their mothers’ full-time care? These questions aren’t the business of employers, the government or the courts, anyway.

Such understandable postmortem second-guessing puts the onus for the Hobby Lobby debacle on women and their advocates, not the court’s right-wing majority or the corporate and religious interests they represent. It’s just one more example of the turmoil unleashed by the court’s radicalism. There will be more as long as this particular 5-4 majority endures.

Shares