My coming out story is personal and idiosyncratic yet also so mundane. For me, and for others of my generation and those of earlier eras, this story figures mightily in our larger narratives of self and identity.

As Joan Didion famously wrote, “we tell ourselves stories in order to live.” A simple and uncontested truism is that all lives are narrated—by ourselves and by others eager to impose some coherence on the chaos of individual trajectory. For minority groups in particular, narratives are constructed as lifelines to each other and as insinuation into the larger stories of national identity and personal triumph. Often quite singular storylines are offered up as both the explanation and the antidote for marginalization and disenfranchisement. The larger social message now, however, is that coming out will promote tolerance. So the tolerance framework depends on coming out but insists that it be done quietly and correctly so as not to stir up or upset heterosexual equanimity. At the same time, and contradictorily, the fantasy of a newly tolerant world downplays the persistence of the closet and therefore conceals the continued strength of homophobia.

So one must be “known” to be tolerated. But not all ways of being out are equally validated, nor are all motivations for coming out similarly situated. In truth, we have different expectations of the people we come out to. Sometimes all we want is to be heard. Sometimes we want to be known. Sometimes we want affirmation of continued love. Sometimes we want to challenge what we understand to be the homophobia of the listener. Sometimes we want to cultivate a new ally. Coming out can be a confession or an assertion, a bold declaration of substantive difference or a quiet acknowledgment that nothing has changed. It can be a nod to the already known and a head-turning about-face. It can—especially in the media-saturated, nanosecond world of Twitter and Facebook and "TMZ"—be a way of heading off the inevitable outing by gossip columnists and bloggers. People can “receive” the coming out of a friend or family member as life altering, or they can hear it for a moment and then seemingly ignore its salience. Certainly, many gays report this response with their parents, when the utterance has only temporary meaning as it is actively disavowed in subsequent familial interactions or when admonitions not to come out to others (grandparents, relatives) are the immediate response.

While it is true that there are eight million (and counting) stories in the naked city, the coming-out story has long been offered as the master narrative of gay life. Indeed, the phrase “coming out” has so permeated cultural understanding that it has even moved from being a story gay people tell about themselves to others to a story multiplied through relationships (for example, when someone “comes out” as having a lesbian daughter or being the child of a gay man).

Further, “coming out” has now become a generic phrase for any previously hidden self-revelation: coming out as HIV-positive, coming out as having cancer, or even the inevitable Oprah-ready coming out as bipolar. And it need not, these days, even imply a secret held with some degree of shame or discomfort: it can simply mean a benign disclosure, as in “last night I came out about my new shoes,” although if they are Jimmy Choos, that might involve some small amount of shame at the exorbitant expense. This democratization or diffusion of coming out tells us a great deal about the declining—or at least changing—status of this particular theme of sexual emergence for gay people. Just as earrings on men or Doc Marten shoes on women were once irredeemably gay signs and are now fully banal parts of everyday straightness, the “de-gaying” of coming out speaks not only to transformations in gay life but to the ways in which gay signs have been both appropriated and accommodated by mainstream heterosexual populations.

Certainly, it was not always this way. The coming-out story— which now seems (at least in the West) almost synonymous with gayness itself—is actually of fairly recent vintage. Coming out as a representational form—as a genre and a tellable tale—really only emerges with the development of a movement for which coming out has salience. For example, the spate of coming-out films in the post-Stonewall period is predicated on that “post-”—on the assertion of a gay and lesbian identity as distinct, as narratively interesting, as a story to be told. In earlier eras, characters that were coded as gay might have been outed in the course of the film, but secrecy and misery were considered the fate of queer characters and most queer actors as well.

This is not to say that a hidden life was the only life available in pre-Stonewall America; people lived in all kinds of permutations of outness prior to the establishment of the coming-out story as the big gay saga of pop culture. History is littered with the marvelous few who insistently lived their lives openly, in the face of ridicule and censure, jail and death. But no one could really come out in films, for example, when the closet wasn’t even an active metaphor. Certainly, internal struggles, self-revelation, and emergence to others existed in pre-gay-movement literature, film, and art. Iconic literary texts such as "The Well of Loneliness" from 1928 or the heartbreaking play and then film "The Children’s Hour" or the ’50s pathos-filled film "Tea and Sympathy" or the myriad pulp novels of the ’50s and ’60s spoke to such stories, even if elliptically. Of course, the pulp novels were unique in that they directly engaged proto-gay audiences with explicit tales of queer sex and romance, often centered around a coming-out theme.

But coming out as a singular process—and the closet as the paradigmatic metaphor for same-sex life itself—depended on the establishment of a gay identity and a gay movement to make it happen. In simple terms, one needed the very category of “the homosexual” to produce the story of coming out. As many historians and theorists have convincingly argued, the homosexual as a distinct category, a demarcated identity (rather than, say, a set of possible sexual acts or preferences) is a very modern invention, as is the heterosexual. Coming out may appear now as the transhistorical and transcultural story of gay life, but it actually was “invented” as recently as the early part of the last century. Like Google, it feels like it’s always been with us because it has so permeated our understanding of gay identity.

Society Girls and Rattling Bones

While it is not clear when, precisely, the term was first used, it certainly derives from referencing—by analogy—the coming out of a debutante into society. This analogy is interesting for many reasons, but what is most striking perhaps is that it prompts us to frame coming out in deeply social terms. This is somewhat at odds with more contemporary versions in which coming out is understood at least in part as an internal process of self-knowledge. Further, in contemporary (really post-Stonewall) parlance, coming out is linked to the idea of the closet, drawing now on a metaphor of “skeletons in the closet.” So if the debutante analogy implied entrance into a specifically social world, with no necessary assumptions about what one was leaving (for the deb, she was making herself eligible for marriage and therefore, in that world, signaling her adulthood), the addition of “the closet” muddied the waters by imbuing this public display with a much more troubled and troubling assumption of shame.

The double analogy (coming out and the closet) marks a shift from a metaphor of social emergence to one of a deeply hidden personal trajectory at the same time that it reformulates the cost of social exclusion (homophobia) on the individual so hidden. Now forever associated, the closet frames coming out as a movement from a place of darkness, hiding, and duplicity. And the closet, now framed as something one comes out of, is understood as imposition and burden, as gay rights pioneer Donald Webster Cory (aka Edward Sagarin) poignantly noted when he wrote as early as the 1950s, “Society has handed me a mask to wear. . . . Everywhere I go, at all times and before all sections of society, I pretend.” So the closet, in this rendering, is a place one is forced into by the agents of what we now call homophobia. Leaving that place—coming out—must then imply an acknowledgment and rejection of that whole rubric of discrimination.

It is also vital to remember that the closet was not and is not the only way to describe historical forms of gay concealment. As historian George Chauncey and others have cautioned, we should be wary of understanding all forms of sexual disguise and subcultural life within the narrow terms of “the closet.” Other divisions (other than “in” or “out”) can be more pertinent to an individual’s self-definition and movement in the world.

Some critics question the centrality of coming out because they believe that the social world has shifted so substantially that it renders “the closet” a minor note in gay identity and culture. Others argue that coming out inevitably mires one in producing the dualistic categories (in/out, gay/straight) that ensnare us to begin with. In addition, the act of coming out—and the attached identities it both assumes and creates—can serve as a sort of policing force, creating, as sociologist Steven Seidman in "Beyond the Closet" notes, “divisions between individuals who are ‘in’ and ‘out’ of the closet. The former are stigmatized as living false, unhappy lives and are pressured to be public without considering that the calculus of benefits and costs vary considerably depending on how individuals are socially positioned.”

While cultural theorists and historians ponder the fate of this persistent frame of reference, many psychologists have also been critical of the developmental models that undergird the coming-out story. The mainstream psychological frameworks often search for (and thus help to produce) a linear model of authenticity that presumes a simple trajectory toward “truth” and self-knowledge and singular sexual identity. Feminist psychologist Lisa Diamond, for example, has complained that many in her field too often seek to “uncover a true and generalizable trajectory of development,” in which autobiographical consistency becomes the “marker of authenticity.” These days, she claims, “researchers are increasingly challenging the notion that sexual identity development is an inherently linear and internally coherent process with an objectively discernible beginning, middle, and end, casting doubt on the notion that developmental psychologists should seek to discover or validate one or more discrete ‘pathways’ from heterosexuality to homosexuality in the first place.” So Diamond and other critics of mainstream psychology seriously undermine the assumptions embedded in the ways psychologists speak of and map out the process of coming out, taking issue with both the singularity (telling a story with one clear sexuality emerging in the end) and the linearity (telling a story that moves from falsehood and self-deception to truth and self-knowledge).

Both the cultural historians and the psychologists would also agree that the idea that “the closet” and “coming out” are one-off experiences is patently false. Not only is coming out an endless and recurrent process so that one is always having to reengage the questions one thought settled, but the closet is of course also a space of variability, inflected geographically and culturally. Someone’s “life in the closet” may be another person’s refusal to be pinned down. While you can’t be a little bit pregnant, you certainly can be a little bit “out.” What seems like a straightforward question (“Are you out?”) will be answered by perhaps the majority of gays in long and meandering sentences rather than a single word. It might be answered emphatically (“Of course I am!”) and then qualified in further conversation. Or it may be the proverbial open secret in which everyone seems to know but no one seems to be able to utter the words. While some are out to absolutely everyone in their lives, the majority of (nonexclusively heterosexual) Americans practice some sort of concealment of their sexual preference, and it is probably the case that all of us—gay, straight, bi, whatever—are even more withholding when it comes to revealing our sexual practices.

But, importantly, these partial or strategic forms of concealment or disavowal need not alter the sense of “outness.” I have been out, for example, since I was sixteen years old but made a deliberate decision not to tell my elderly immigrant grandparents, not really for fear of their rejection but frankly because it seemed too much effort for little payoff. While this might have been a source of some internal conflict for me (and a source of repressed laughter between myself and my mother, when it became clear that my grandmother had constructed an alternative narrative of workaholic but heterosexual singledom for me), it did not alter my sense of being out, because for me that designation had everything to do with participation in a gay community and openness with people close to me. I saw my grandparents infrequently, so the management of that concealment hardly affected my everyday (and out) life. When they both died in their late nineties—without knowing I was gay—that omission seemed a negligible aspect of my overall sense of loss.

Or, alternately, there are situations when one’s gayness is seemingly undermined by practices deemed irrevocably heterosexual. This has been the experience of so many gay parents whose parental role is perceived to be at odds with their sexuality. For example, years ago when I announced my pregnancy to the chair of my department, her response was both hilarious and horrifying: “But I thought you were a lesbian!” This reaction is diminishing of course and happens less often when two parents are present (I was a single mother), but gay parents remain “mistaken” for heterosexual all the time.

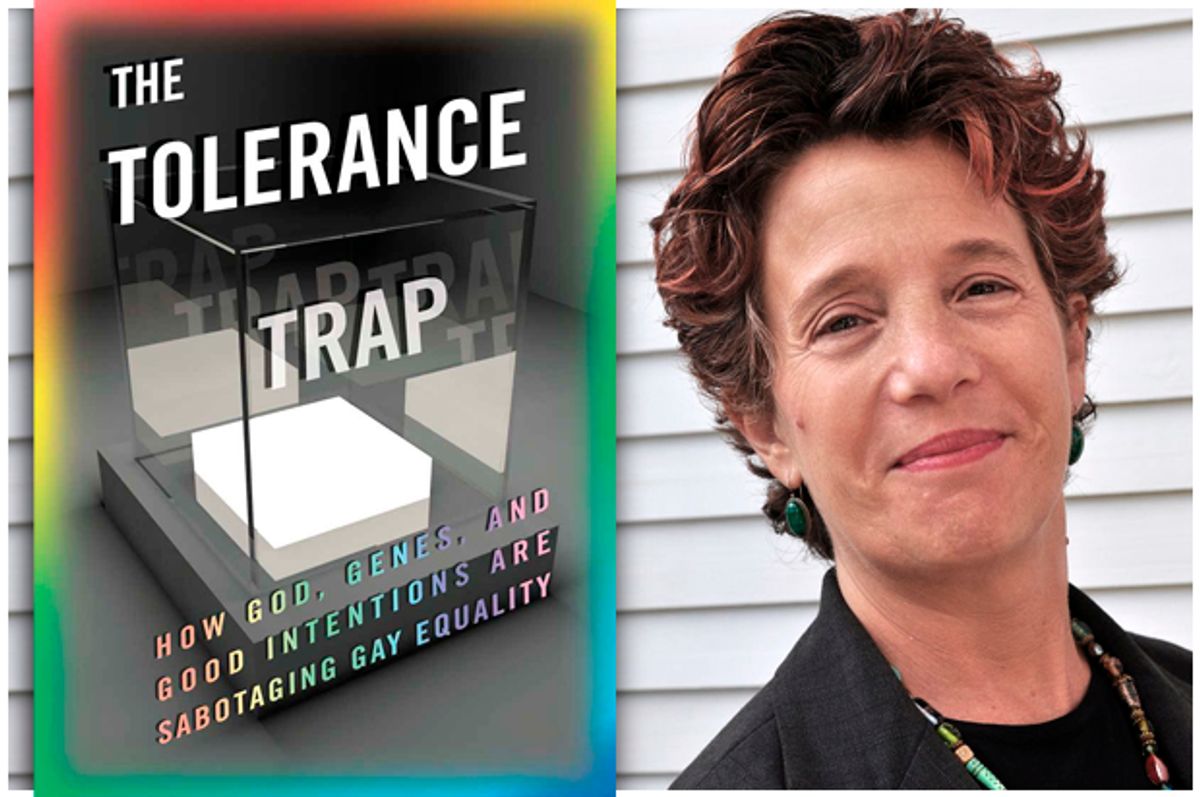

Reprinted with permission from the book "The Tolerance Trap: How God, Genes, and Good Intentions are Sabotaging Gay Equality." Copyright © 2014 by Suzanna Danuta Walters. Published by NYU Press.

Shares