Last week, for one brief moment, Ann Coulter made a lick of sense, which is surely one of the signs of the apocalypse. She advised Mississippi Tea Party challenger Chris McDaniel and his supporters to give up their battle to overturn his runoff loss to incumbent Sen. Thad Cochran, because it would only sour his future prospects. “Hoping for yet a third primary vote, McDaniel's crew is going to prevent him from having any political career, ever again,” she wrote, in a rare-as-hens-teeth moment of clarity and common sense.

Of course, as Brad Friedman pointed out, Coulter has her own personal history of possible fraudulent voting in two states, which can go a long ways toward explaining her distaste for looking into alleged voter fraud, which was the real main thrust of her argument. Even candidates who lose by fraud lose again by fighting, Coulter explained, but they triumph when they walk away. It's a plausible argument in theory, perhaps. But given how rare actual voter fraud is, it's more just-so story than theory.

Coulter predictably cited two elections Republicans lost because non-white voters turned out in unexpectedly high numbers — John Thune's loss to Sen. Tim Johnson in South Dakota in 2002, and Bob Dornan's loss of California's 46th Congressional District to Loretta Sanchez in 1996. Ignored in her analysis were the actual demographics and other fundamentals in the two cases — strongly trending demographics that spelled doom for Dornan, while President Bush at the top of the ticket in 2004 gave Thune a significant boost in his solid red state.

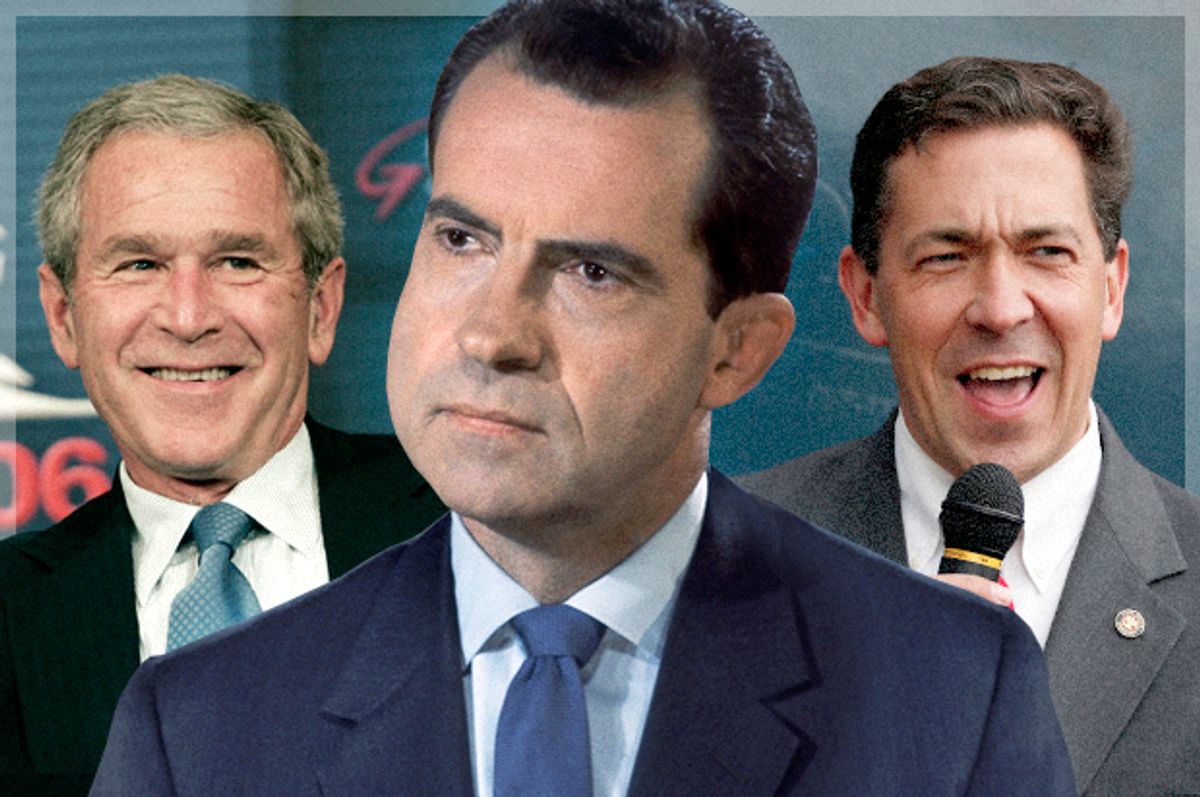

But Coulter also cited Richard Nixon's loss of the presidential election in 1960 as yet another stolen election — an equally unfounded right-wing myth that has remarkably been accepted by the mainstream for decades now. Commenting on Coulter's column on July 10 on "The Last Word With Lawrence O'Donnell" (video/transcript), liberal columnist E.J. Dionne explicitly echoed Coulter's Nixon-was-robbed claim, and O'Donnell himself at least tacitly agreed:

DIONNE: Her example number one was good old Richard Nixon.

O'DONNELL: Yes.

DIONNE: Who could have complained about stolen votes in Illinois and Texas. It`s still not clear to me he would have won, but — he had a case to make and he didn't make it. And —

O'DONNELL: And eight years later became president.

DIONNE: Correct.

O'DONNELL: Yes.

Of course, the story is preposterous. Richard Nixon, the high-minded gracious loser? Even Nixon's mother wouldn't believe that one.Yet, somehow it's become part of the nation's political lore — Richard Nixon's most successful, most enduring lie.

The example of Nixon's high-mindedness was prominently floated during the 2000 Florida election contest, as a way of slamming Al Gore, but it was all a myth, according to David Greenberg, an historian finishing his dissertation, which later became the book, "Nixon's Shadow: The History Of An Image." On Nov. 10, 2000, he wrote an op-ed for the LA Times, “It's a Myth That Nixon Acquiesced in 1960,” in which he wrote:

It's certainly true that Nixon claimed he spurned advice from President Eisenhower to dispute the election results in order to spare the country a constitutional crisis. (He was saving that for 1973.) And, indeed, Nixon's version of events now borders on accepted fact. But it's a myth and a false precedent....

[W]hile Nixon publicly pooh-poohed a challenge, his allies aggressively pursued one. Much of this history has, incredibly, been forgotten as biographers such as Stephen E. Ambrose have propounded Nixon's line. But a glance at the 1960 newspapers shows that GOP leaders tried to undo the results. They knew it was a longshot, but the effort continued right up until the electoral college certified Kennedy's win on Dec. 19.

Nixon himself struck a hands-off pose, but one word from him, and it's hard to see how any challenges would have continued. It was typical Tricky Dick all the way: cover-up and conspiracy seamlessly combined.

I was blogging about the Florida election battle at the Los Angeles Indymedia site, and interviewed Greenberg one week later. He discussed the reasons why such myths persist, who was involved in pushing the recounts, and how they came up short, among other topics. At one point, I asked about Nixon's role in casting himself as hero:

Question: You write that Eisenhower quickly soured on the idea [of contesting the election], but that Nixon claimed that he was the one advocating restraint. Tell us more about this.

Greenberg: There have been a number of people who've written about this, but the one I've relied on for the Eisenhower role is Ralph de Toledano, a conservative journalist who wrote for Newsweek and then for National Review.

He wrote a biography of Nixon, "One Man Alone," which he updated in 1969. In the updated version he said that Eisenhower's about-face wasn't widely known until after his death. Apparently Attorney General Bill Rogers also didn't want the challenge to go forward. So with Eisenhower and Rogers against it was difficult for Nixon to go ahead in public. Toledano later said that it was "The first time I ever caught Nixon in a lie."

While most of the attention focused on Illinois (more on that below), some of the challenges seemed particularly far-fetched:

Question: You mentioned Pennsylvania was on their list, even though Kennedy's margin was better than 130,000 votes. Any idea why they included it?

Greenberg: Senator Henry Jackson accused the Republicans of trying to begin a fishing expedition. It seems that they were trying to generate uncertainty and concern, and maybe if they'd find some improprieties in a state like Pennsylvania, it would just strengthen their case that Kennedy was not legitimate as President. That's the only inference I can draw in this case.

I also asked how long the challenges lasted:

Greenberg: Well into December and certainly up until the time that the Electoral College met. New Jersey [margin 22,000+ votes] stopped its recount on December 1 or 2. Hawaii didn't name its electors until after the Electoral College met on the 19th of December. In other words, in Hawaii's case, the recount Extended past the date the Electoral College met. Ironically, Hawaii went the opposite way--from Nixon to Kennedy. Pierre Salinger, who was Kennedy's press secretary, is quoted in the New York Times on December 30, pointing out that Republicans asked for all these recounts and didn't win anything as a result, while the Democrats asked for just one recount and won it.

And I asked Greenberg about the major players involved in the recount effort.

Greenberg: [T]here was Thurston Morton, chair of the RNC (Republican National Committee) and Senator from Kentucky. There was Meade Alcorn, lawyer for the RNC. Then there were three Nixon campaign advisors, Robert H. Finch, Leonard W. Hall and Fred Scribner....

Finch and Hall were Nixon intimates. Finch was quite close with Nixon and served in his cabinet when Nixon was President. Hall had been RNC Chairman. Scribner was another campaign aide. They were all involved in the campaign and they quickly got involved in the recount efforts. That's the main reason to surmise that Nixon was involved too. And of course Finch and others, including Nixon, told the public that Nixon was not involved. It's very hard to say what level of involvement Nixon had. It seems to me quite plausible that Nixon was remotely, or perhaps tacitly involved, even if he wasn't directing the effort. But that's impossible to determine at this point.

Plausible deniability. What more could a man like Nixon possibly want as his default, fall-back position? In "Nixon's Shadow," Greenberg would write:

He publicly distanced himself from the challenges, knowing, as he later wrote, that "charges of 'sore loser' would follow me through history and remove any possibility of a further political career." Meanwhile, his aides Bob Finch and Len Hall, along with Republican National Committee chairman Thruston Morton and General Counsel Meade Alcorn, waged battle. They filed lawsuits, secured recounts, had the government empanel grand juries, formed a "Nixon Recount Committee" that raised at least $100,00, and stoked the fire with inflammatory comments to the press.... After stringing out the election through mid-December, however, they lost two critical court cases and had to close up shop.

Despite the failure to establish Kennedy's victory as illegitimate, Nixon nursed a grudge. At a Christmas party that he and Pat threw, the outgoing vice president was heard to greet guests with, "We won, but they stole it from us." ... Nixon's belief that Kennedy won the office illegally may also have emboldened him to view the Watergate tactics he sanctioned before the 1972 election as legitimate.

As this passage suggests, part of the purpose of the Nixon recount effort was to delegitimate Kennedy's presidency, not just deprive him of a mandate. The parallels are unmistakable with how Republicans treat Obama today. But in those days, you had to play your cards much closer to the vest.

There actually was a chance that Kennedy could have been defeated — but that would have depended on Southern Democrats defecting — something which actually did occur through unpledged slates of electors in two states. But more were needed to block Kennedy's election, unless Nixon could win Texas as well — a very tall order, considering the 46,000-vote margin there. A federal court decision stopped those prospects cold. Greenberg also called my attention to the most thorough analysis of the election contest in Illinois, "Courthouse over White House: Chicago and the Presidential Election of 1960" by Edmund F. Kallina Jr., which contained the following description of Nixon's limited options:

Nixon must have been aware that the chances of upsetting the results of the election were negligible.... A win would require reversals in both Illinois and Texas or in one of these two states and two other states. Such upsets were not in the cards. It was within the realm of possibility that Kennedy's total of 297 could be driven below the necessary 269, but it would have meant cutting a deal with southern electors who were less interested in helping Nixon than in gaining leverage over Kennedy. If Kennedy had been denied the necessary electoral votes and the election had been thrown into the House of Representatives, not only would Nixon have been subjected to considerable criticism but there was little chance that he could have emerged the victor. Such squalid dealing, which would have involved major concessions on civil rights, was unthinkable to Nixon and almost every other Republican leader. In short, Nixon could see that a bid to overturn the election had almost no chance of succeeding and that it would have stamped him a poor loser.

Such were the real-world prospects Nixon faced. So why not make the best of things, and pretend to be noble, when there's nothing else to be done? You don't have to be an evil genius to figure this one out.

The greatest value of Kalina's book, however, lies in its tightly-detailed, carefully-argued account of the battles that unfolded in Illinois, which Kennedy won by 9,000 votes. As the title suggests, the Daley machine was involved in significant vote-stealing and suppression — its reputation on this score was well deserved. But, also true to form, its focus was not on the presidential race — it was on the Cook County State's Attorney race, where a potential future challenger to Mayor Daley, Benjamin Adamowski (a former Democrat) was narrowly defeated for re-election. In the limited recount that was conducted after the election, far more votes shifted over to Adamowski than did to Nixon:

The evidence from the discovery recount figures is circumstantial but conclusive. Nixon's gains (and those of Carpenter and Smith [two other Republican candidates]) were derivative of Adamowski's, not vice versa. Insofar as there was an effort to cheat Republican candidates, it centered on Adamowski rather than Nixon.

Kalina also makes it clear that the GOP challengers were similarly focused on state and local politics as well:

Based on interviews from 1974-75, it appears that almost none of those involved in the discovery recount actually expected that they could upset the presidential tally. They were never certain that a recount was permissible under existing Illinois law or whether, if it were, it was possible to obtain an accurate recount. Rather their aims were more limited: to expose to the glare of national publicity how Chicago Democrats conducted elections and thereby to rally support, to lay a foundation for election reform, and to get a head start on the next election.

And in this, they proved rather successful, as Kalina noted in a much more recent and more broadly-focused book, "Kennedy v. Nixon: The Presidential Election of 1960." There, he wrote:

Vote fraud mobilized the party rank-and-file. Republicans successfully exploited this issue in Chicago and in Illinois for more than a decade. In 1968, the party launched a massive poll-watching effort that helped Nixon carry the state. If Republicans thought that Democrats had treated them unfairly in 1960, both the state party and the national party profited from the abuse throughout the next decade.

In the end, significantly, it was a Republican-dominated election board that certified the Illinois election for Kennedy. There was electoral (not voter) fraud, but not nearly enough to change the election. All of which made Nixon's play letter perfect — pretending disinterest, while letting others fight tooth and nail in the trenches, to alter the presumptions in a future contest.

Although Nixon personally kept out of the fight, there was no question but that it continued after the election — and that historians have taken Nixon's self-description at face value, rather than considering the actual battles that ensued, which were widely reported in the press at the time.

“There's a lot of historians I respect repeating this story,” Greenberg told me. “Once stories like this have been repeated so many times, you don't just go and dig up the original sources to recheck them. For the most part, how Nixon behaved after the 1960 election is not the sort of thing you're going to be digging into as an historian. Historians have to depend on one another, otherwise there could be little progress made. But it does allow for mistaken accounts like this to become very well-established.” It also feeds into the balance narrative, which many historians find as addicting as journalists do. What better way to prove you've got a balanced, unprejudiced view of Nixon than to parrot his claim that he magnanimously accepted defeat, despite being cheated out of the White House?

What difference does it make, after all these years? Just consider how Republicans have refused to accept the presidency of Barack Obama. Yes, there's a significant element of racial animus involved — as well as identity-protective resentment, given how thoroughly conservatism had been discredited by the Bush Administration before him. But the “Nixon Recount Committee” effort of 1960 points to a more enduring factor that is also part of the mix, a reflection of a sense of entitlement, which was also seen in how Republicans responded to Clinton's election as well. In our interview, Greenberg told me:

Of course, most of them probably didn't really think they could win. But they did think they could taint Kennedy's victory and deprive him of the so-called mandate, which they felt was necessary in order to govern successfully. They could also get their own rank and file exercised about this and have a great issue to run on in 1962 and 1964.

For example, Walter Judd, who was a prominent Republican Congressman from Minnesota, gave a speech at a meeting of the Republican National Women's Club in which he said that in Illinois and Texas the Democrats had stolen the election. It's a good example of how some Republican leaders were using it for the future.

We tend to forget just how successful the Republicans were on this score — in part because Kennedy's legions of boosters played up his successes while downplaying his frustrations, and because his assassination has forever marked his presidency with the sense of possibilities unfulfilled. But the reality is that most of what Kennedy wanted to do was left unfinished, and much of Johnson's early success depended on shrewdly taking advantage of Kennedy's de facto martyrdom. The American people truly were enchanted with the Kennedy Camelot myth, and Kennedy was far ahead of any prospective Republican challenger in the last Gallup poll before he died — and yet, Kennedy's legislative record remains substantially less impressive than his popularity would have suggested, in part because certain segments of the population remained bitterly hostile to him. It's hard to ignore the Republican efforts to delegitimize him in advance, once you've had your eyes opened to what they were actually doing.

Shares