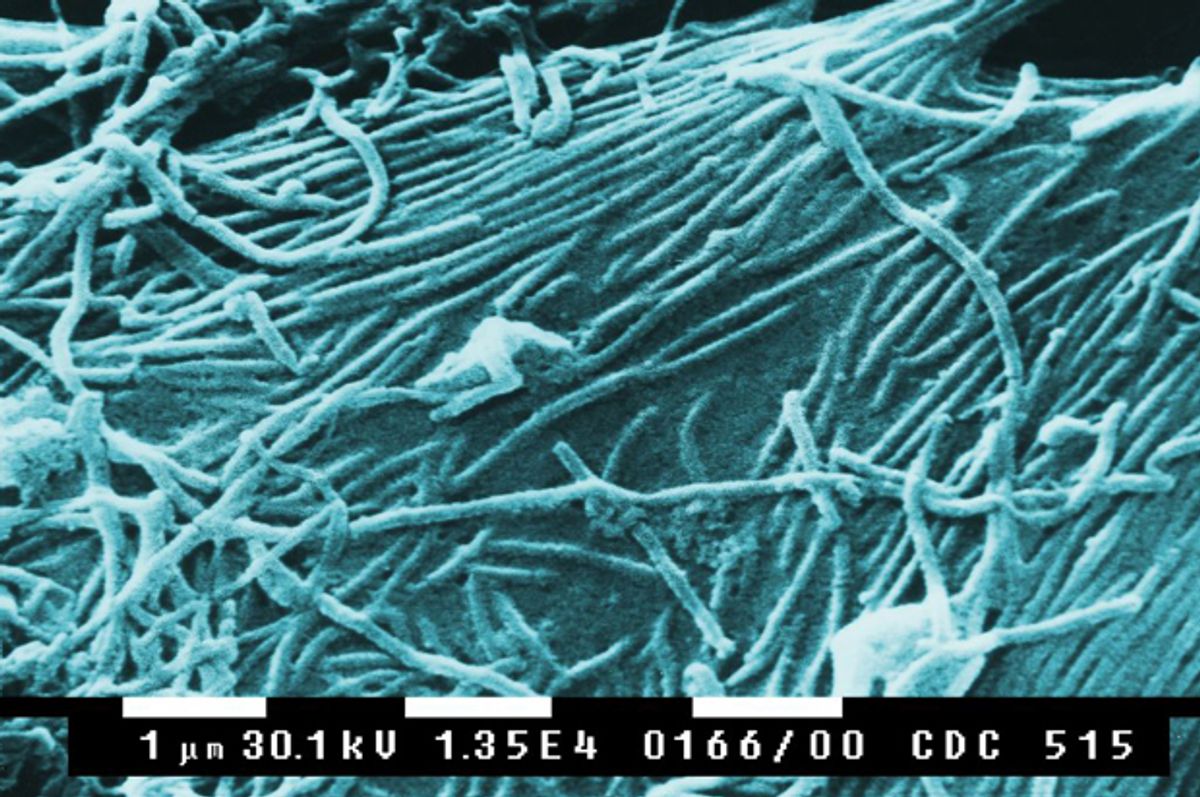

The present Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone is the deadliest on record. On June 23, the World Health Organization reported 635 Ebola cases, including 399 deaths. By July 12, the figures were up to 964 cases, including 603 deaths. Doctors Without Borders and the World Health Organization are providing substantial medical personnel and resources on the ground in order to help contain the outbreak.

The United States, according to the CDC, has sent a seven-person team to help in Guinea, and provided protective clothing and equipment for healthcare workers in all three countries. In the grand scheme of things, that is a minimal amount of aid -- echoed by the minimal coverage the outbreak has garnered in U.S. media. (Far more attention was afforded GOP Congressman Phil Gingrey’s outlandish and factually implausible comments about refugee children crossing the border bringing Ebola into the United States from Central America.)

There is more than one way to interpret America's disinterest. One is racism -- the sense that the people dying of Ebola are so different from “us” that we really can’t identify with them. Another is compassion fatigue. Isn’t there always some horrible disease afflicting Africa and Africans?

Indeed, many of the English-language articles that have been written about the Ebola outbreak focus on “ignorant” and “superstitious” Africans who give more credence to witchcraft than to modern medicine.

The key to halting Ebola is isolating the sick, but fear and panic have sent some patients into hiding, complicating efforts to stop its spread. … Preachers are calling for divine intervention, and panicked residents in remote areas have on multiple occasions attacked the very health workers sent to help them. In one town in Sierra Leone, residents partially burned down a treatment centre over fears that the drugs given to victims were actually causing the disease.

This analysis, picked up by several news outlets, simultaneously reveals the kind of xenophobic Western mindset that victims of the Ebola outbreak distrust, and hints at why Western readers do not seem all that interested in learning about or from the outbreak.

The suspicions with which many people in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leona regard Western interventions make sense. Healthcare workers are particularly hard-hit by Ebola, and workers and other patients who hadn't been infected can return home not knowing they now carry the disease, transmitting the virus to their families and communities. International relief organizations in these countries set up emergency treatment that will be taken down when the immediate threat is over. But family sticks around forever. Refraining from leaving sick relatives in hospitals (that typically utilize isolation as the sole means of containing the Ebola virus) can be a pragmatic and sensible choice to rely on the kinship and community networks that have kept people alive in the past.

From my perch as a medical sociologist, the claim that mobs attacking treatment centers are panicking reveals “troubling truths" regarding the Western track record of medical experiments and geopolitical ambitions in Africa. Distrust of Western medicine may have less to do with superstition than with history: forced sterilizations in Peru; the intentional infection of Guatemalans with gonorrhea and syphilis; marketing campaigns urging mothers in countries lacking safe water supplies to replace breastfeeding with infant formula so that women could work in western-owned factories; the sale in Africa of pharmaceuticals that passed their expiration date for sale in the West; the harvesting of organs in India for transplants to wealthy foreigners.

In sub-Saharan Africa, outbreaks of new diseases such as Ebola (first identified in 1976) echo the spread of industrialization, urbanization, unprecedented militarization (funded by western countries), deforestation and the destruction of eco-systems that have forced communities to expand their search for food into territories that traditionally were not used for that purpose. In reports in the English-language press, however, there is little consideration of the political and economic structural forces that gave rise to the emergence and spread of Ebola. Rather, as Jared Jones writes, “African ‘Otherness’ overpowers the possibility of a non-cultural causality in the dominant discourse, and other factors are left unexamined as potentially causal or exacerbating.” Attention to sorcery rather than the inequalities of globalization obscures the fact that the biggest leaps in life expectancy in the U.S. and Europe came about because of massive government-funded public health measures -- sewage systems and clean water supplies – not because we gave up our religious beliefs.

The articles I read in the English-language press decry the absence of functioning healthcare infrastructures in the African nations hit by the Ebola virus. But I am not convinced that the United States would do much better. There are a great many things that western medical institutions and personnel do extraordinarily well. We have sophisticated surgical technology and an advanced pharmacopeia of medicines to treat hundreds of diseases. But the bulk of our medical resources go towards curing rather than prevention. What we do dedicate to prevention tends to be limited to proximate factors such as germs and personal behaviors such as smoking that make individuals sick. We also divert resources into campaigns for procedures such as mammograms which detect but do not prevent disease. We pay less attention to poverty, inequality, environmental degradation and, yes, globalization, as root causes of sickness.

Perhaps it is not surprising that the United States has contributed so minimally to managing the Ebola outbreak. Effective public health endeavors need organized and sustainable systems for preventing the spread of disease. And, as I have argued before, the United States does not have a healthcare system. “System” denotes an overarching set of principles, practices, procedures and organizational structures, whereas our U.S. healthcare landscape is a decentralized and incoherent hodgepodge of financing and delivery mechanisms lacking rational methods for setting priorities.

Services and regulations, as well as thresholds for Medicaid eligibility, vary enormously from state to state. Municipal, county and state health departments rarely have mechanisms to keep track of patients who move to another jurisdiction. Hospitals around the country and even within one city or state use incompatible medical records. (Even the federal government's Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense records are mutually inaccessible.) We have for-profit and not-for-profit hospitals. (And it’s often difficult to tell which is which.) Though many of us believe that emergency rooms serve as a safety net, federal law only requires emergency rooms to assess and stabilize patients (and they are allowed to charge a whole lot to do so), not to cure them. Walk-in clinics are proliferating in Wal-Mart and CVS branches. Hundreds of for-profit and not-for-profit insurance companies compete for “good” (that is, well-paying and relatively healthy) patients and customers. Behavioral and oral healthcare are almost never integrated with the rest of healthcare. And the Affordable Care Act — touting that “consumers” can “choose” the insurance plans that “best fit their needs” — is not designed to turn this chaos into any sort of longterm sustainable system.

We need to learn about public health emergencies around the world not only because they might become our emergencies, but also because those emergencies could be better contained and managed if we were to invest our expertise, our attention and our resources into community, national and international health preservation. For a fraction of the money that Western countries have poured into military campaigns in Africa, it would have been possible to support local governments in building functioning public health infrastructures. But let’s also not forget that despite spending more on healthcare per person than any other country in the world, here in the U.S. we are dead last among developed countries in health and life-expectancy, according to a recent study of 11 nations by the Commonwealth Fund. Ignoring the reality that the health of each of us is inexorably intertwined with the health of others is a collective disaster-in-the-making.

Shares