Brando Skyhorse’s mother used to tell him about being saved from Ted Bundy by the Hell’s Angels, even though this never really happened. And she named him after Marlon, the actor, and Paul Skyhorse Johnson, a criminal, even though his real father was a Mexican named Candido García Ulloa. She’d invented the family’s Native American heritage entirely.

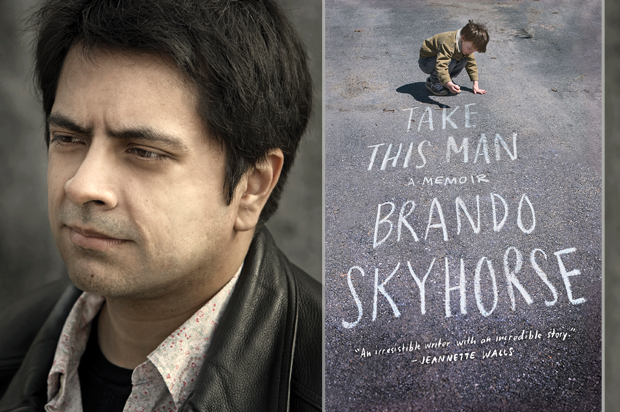

It was writer’s block that prompted Brando Skyhorse to write a letter to his father, and the response he received inspired him to write “Take This Man”: a strange, singularly captivating memoir about the relationship between fact and fiction in his family mythology. Skyhorse was raised in a turbulent household consisting of his mother and grandmother–and, over the years, five different step-fathers plus one man, Frank, who dated but never married his mother.

How did you deal with such a chaotic upbringing?

I tried a variety of different coping mechanisms, most of which failed spectacularly. It’s not like I figured it out. I stumbled into surviving because everything else failed. I tried suggesting family therapy, and bonding with my stepfathers, because it was easier than incurring my mother’s wrath. I acted my way though it. I played the survivor card in whatever scenario I was in. My mother enlisted me as her consigliere—like Robert Duval’s character in “The Godfather” [Brando’s mother’s favorite film, along with Pacino’s “Scarface”]. Whenever there was a fight or argument, she’d pull me aside and I’d tell her what I thought. When they made up, she used everything I said against me. I learned that if I could bond with the least violent part of the triangle, I could survive for a while. This sounds mercenary and cruel—because these are family members—but you do what you have to to adapt to this kind of circus. This didn’t mean that there weren’t decent stretches—like with Pat—but that’s why his departure was so heartbreaking.

What was it like to pass as Native American, even though you are Mexican?

My mother’s curiosity about American Indians extended to the surface. I find myself thinking about how she was so passionate about how Native Americans were treated poorly in this country, but she appropriated their name and culture, which was one of the most despicable things. Paul was an American Indian, and whether he thought it was cool for us to take his name was irrelevant.

When I found out I was Mexican, I carried around this guilt. When I was playing the role, I could survive through the day, but when I had to, to play the additional role, as the progeny of a Chief, that’s when things started to crack. When I got older, I intuitively understood it was wrong, a disservice, and greatly disrespectful. There was also a part of me that thought: I’m going to get found out. I’m going to run into an actual America Indian, and they are going to kick my ass.

But you kept your name, Brando Skyhorse…

I often get, “what a beautiful name” from people. They always ask: Is that my real name? The short answer is: technically, yes. They want that connection. Once you keep getting that affirmation, you roll with is. Sometimes you encourage it.

I will feel a sense of connection with a tribe when I read about it, which is insane. People will try to offer excuses for what my mother did. I still try to figure out how to grapple with issues of identity and culture, and that’s why I wrote the book. It’s the first blueprint for this kind of passing.

Your mother told lies, but as a writer, do you identify with a certain kind of invention and reinvention?

They are distinct, parallel universes but they don’t overlap. She was a scared, old, emotionally dysfunctional person, who was worn down by life. She needed her lies—her armor—to get through the days. People were drawn to it. She wasn’t trying to be deliberately malicious. It was her coping mechanism for living with my grandmother, who was a badass in her 60s, so you can imagine what it was like for my mother to grow up as her child. She needed to protect herself. You can see how I evolved—a reaction to the generation who raised me. All of their actions and consequences led to me choosing the career path I am on. I don’t lie in person, but I love the idea of creating a fictional universe, where I can go and hide and be safe. She’s the ward of everything in her world, which she wanted to be real. I am the ward of everything on the page.

How did reading help you cope?

I went to the library frequently as a kid, which was a big deal for me in Echo Park in the 1970s. This was an area with no bookstores. I took a bus to a nicer neighborhood for a half hour. So I made the association of books and a better world. Books kept me out of harm’s way, and kept me in the house. I got lots of stuff that was off the beaten path. But college was when I started reading on my own. Two biggest influences for me were William Faulkner’s “Absalom, Absalom,” with its rich language, and Bret Easton Ellis’ “Less than Zero”—which seems weird, but reading that book for me, was like when musicians say they heard the Ramones for the first time. It was so direct and straightforward. That spare prose was something I could relate to and understand. The lightbulb went off over my head. I wouldn’t fit into super rich LA or the South, but I found my own voice.

What about music? You’ve said you have a fondness for Morrissey–

A close male friend of mine named Mario, who was Mexican American, 6’ 6” and wore shades at school. A badass. He was the cool guy. I don’t know how we became friends but all my clothes and musical taste I got from him. I wasn’t into music, but I adopted all his tastes initially. It felt like being part of a clique, which was new to me. We had a multi-cultural group of all the kids who didn’t fit in. We listened to alternative music, and Morrissey. I want to track Mario down to find out how he discovered him. Morrissey sings in an emotional way. His voice is an instrument, and his songs are confessional, dramatic, and very reminiscent of the Mexican expressive singers who hold a note for several seconds. Subconsciously, I was trying to find my version, done in English, of the kind of music my grandmother listened to. I didn’t know the culture of Mexicans listening to Morrissey existed until later.

What was it like to dramatize your own life in a memoir? Did you ever feel like you were stretching reality for the sake of narrative?

Having worked in publishing during the era of several prominent memoir meltdowns, I saw how things unraveled over and over again. If I wrote my book, I would be subjected to a much greater scrutiny because of these projects. I wanted to rely solely on what I had memories of, but they are elastic because you are a child. Crucial scenes recounted in “Take This Man”—of my mom trying to put my head in the toilet—are very specific, and there is no dialogue in them, because I don’t remember what she said. I had a good approximation of what she said leading up to that, but it’s not a word for word recreation. I remember what I was feeling because it was terrifying.

Frank was key, too, because he survived it. He didn’t know my mother wasn’t an American Indian until I started talking to him about the book—which shows how deceptive she was. He dated her off and on for years, but he couldn’t be certain until I confirmed it for him. His response was “She believed it” and that made it OK. He remembers our first meeting, and recreated that memory for me. He could never forget those moments. I spoke with Candy [Skyhorse’s father, Candido], and he spoke about leaving the house as if it happened yesterday. I couldn’t remember it, but I only had to ask, “What happened?” It was a story he was waiting to tell for a very long time.

I also did some detective work, finding out about the two Paul Skyhorses, what they were in jail for, and finding my mother’s name in his papers sent to me from prisons, etc. All of these created the mosaic that gave the book its backbone to guarantee to the reader that this is my best effort to recreate what happened.

To write this memoir the bullshit way, I would have written my mother’s stories verbatim.