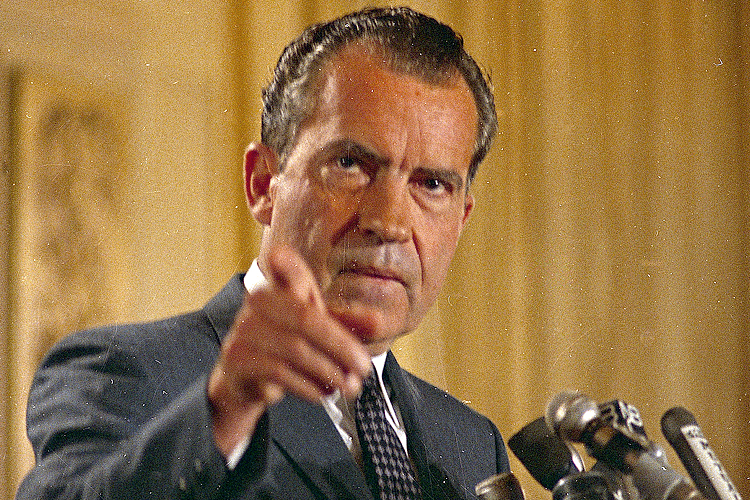

Richard Nixon’s long quest for the White House resulted in a 1968 triumph, due in part to a stated commitment to reestablishing “law and order.” Nixon famously claimed that he represented the “silent majority” of middle-class white Americans who were tired of the protests, riots and youth militancy that had come to dominate the cultural landscape in the late 1960s. Key to the “law and order” rhetoric was his promise to restore respect for traditional authority, especially toward the police, who were called “pigs” and worse by young adults in the antiwar, hippie and black power movements.

In the 46 years since the 1968 election, American conservatism has undergone a radical transformation with regard to its relationship to authority. Rather than encourage deference to lawful authorities, modern-day conservatives, particularly those in the Tea Party movement, regularly boast of their refusal to respect what they believe to be the illegitimacy of the federal government. Conservative media outlets, from Fox News to talk radio to blogs, regularly provide their audiences with breathless accounts of how the government is planning to imprison conservative activists, how the Affordable Care Act is “destroying religious liberty,” or how President Obama is secretly allied with the Muslim Brotherhood or the Communist Party.

Republicans, who in an earlier age shrank in horror when Black Panthers paraded around in public with loaded guns, now glorify criminals like Cliven Bundy and see no problem with brandishing semi-automatic weapons in stores, restaurants and political rallies. Supposedly mainstream conservatives such as Sarah Palin and Mike Huckabee offer ominous threats about an impending revolution. Not even the police are free from conservative rage, as the recent spree killings of police officers by anti-government husband and wife militants in Las Vegas indicate. How did American conservatism morph from the silent majority of law and order into advocates of violence against the government?

One could argue that the so-called silent majority was never interested in law and order in the first place. The American conservative tradition has always been sympathetic to the white Southern narrative, which paints the average Confederate soldier as a noble patriot, who fought for family, tradition and the right to conduct his affairs without government interference. Taking a pro-South position is inherently problematic, since it put the conservative in the awkward position of valorizing a group who took up arms against the United States government, an action they might consider to be beyond the pale if committed by black people, Native Americans or another minority population. However, if one assumes that it is lawful for whites to rebel against the government, but other racial groups must remain subordinate to whites, then the Confederate betrayal can be reconciled with the American revolutionary tradition going back to Valley Forge.

The conservative embrace of violence and lawlessness is best illustrated by the practice of lynching, which reinforced the legal disenfranchisement of black people through the use of extralegal violence. For much of the pre-civil rights era, the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups were not only given free rein to operate, but their violent escapades were glamorized in films like “The Birth of a Nation” (1915) and “Gone With the Wind” (1939), and the erection of public buildings and monuments named after prominent Confederates and Klansmen. Photographs of lynchings were even printed on mass-produced postcards in the early 20th century, until the Postal Service banned the sending of such graphic images through the mail. The perpetrators of this organized violence flaunted their bloody accomplishments, knowing full well that they would never have to suffer any consequences, legal, social or monetary for their crimes, as shown by the actions of Emmett Till’s garrulous murderers, who sold their story to Look magazine after an all-white jury acquitted them. Although there were more than 200 attempts to pass federal anti-lynching legislation between 1868 and 1968 (three of which passed the Senate), Southern Democratic senators stymied the passage of these bills. For conservatives, violence aimed at upholding white supremacy was not only justified, but necessary.

This explains why a New England conservative like William F. Buckley would state that the real tragedy of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing, which killed four black girls, was that it made white people look bad. As his National Review wrote:

Let us gently say the fiend who set off the bomb does not have the sympathy of the white population in the South; in fact, he set back the cause of the white people there so dramatically as to raise the question whether in fact the explosion was the act of a provocateur — of a Communist, or of a crazed Negro.

And let it be said that the convulsions that go on, and are bound to continue, have resulted from revolutionary assaults on the status quo, and a contempt for the law, which are traceable to the Supreme Court’s manifest contempt for the settled traditions of Constitutional practice.Certainly it now appears that Birmingham’s Negroes will never be content so long as the white population is free to be free.

Here we have Buckley, who famously purged National Review of the John Birch Society members, blaming the violence in Birmingham, not on white racists who wanted to deprive blacks of their rights as American citizens, but on the “lawlessness” caused by the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Had Buckley been using the parlance of 2014, he would have said that the justices of the Supreme Court were guilty of “judicial activism.” While Buckley may have shunned the more vulgar expressions of racism and paranoia found in the John Birch Society, he was in agreement with them that the civil rights movement was a dangerous plot to undermine the power of white America that needed to be stopped, whether by the political process or through terroristic methods.

Buckley’s shocking reaction to the Sixteen Street Baptist Church bombing illustrates something that is downplayed in contemporary political discourse, namely that few if any in the Cold War-era American conservative movement favored civil rights for black people, from rising stars like Ronald Reagan to entrenched Dixiecrats like Strom Thurmond. Although the civil rights movement generally operated on the principle of nonviolent civil disobedience, particularly the wing presided over by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the sight of black Southerners defying Jim Crow laws terrified many whites, even if no weapons were involved. When the National Guard was called out to integrate Central High in Little Rock, Arkansas, many Southern whites feared that they were witnessing the beginning of another Civil War. The consensus among American conservatives was that the civil rights movement was a disruptive nuisance at best and a fifth column for the Soviet Union at worst. Operating from the assumption that integration was inherently “communist,” mid-century conservatives considered black aspirations to full citizenship to be ipso facto illegitimate, which mean that whites were justified in using deadly force to defeat the civil rights movement, whether in the state-sponsored violence of the COINTELPRO program or the thuggery of the Klan.

Given this background, it should be obvious that the so-called silent majority was only in favor of “law and order” when the legal system was rigged to favor white supremacy. When the legislation was passed to end de jure segregation and attempt to redress some of the injustices it caused (e.g., affirmative action, school desegregation orders, SNAP), conservatives suddenly decided that the government was illegitimate. The rise of the Tea Party after the election of Barack Obama is not coincidental.

The bulk of conservative violence has never been committed by lynch mobs or Klansmen, but by the silent majority who preferred to maintain their “way of life” at the expense of civil rights and basic human decency, from the ordinary conservative whites who never questioned the assumptions that their society was built upon, to “intellectuals” like William F. Buckley who sought to justify terrorism. The very silence of the silent majority shows that they ultimately cared little about law or order, but about maintaining their exalted position in American society.