The latest news out of Iraq has to be encouraging for the vocal and distressingly influential sect of politicians and commentators who consider American military power the best and only solution to international strife. President Obama’s initial plan to deal with the threat posed by the terrorist group ISIS was the deployment of 300 non-combat military advisors to Iraq. That plan then expanded to include humanitarian airdrops to assist Iraqi civilians under threat from ISIS. Then we started conducting targeted airstrikes on the group. Now we’re providing direct military aid to Kurdish forces in the north of the country. The mission is creep-creeping along and the commitment of U.S. resources is slowly expanding.

As Ryan Cooper points out at The Week, the justification for U.S. military involvement in Iraq this time around enjoys a high level of credibility when stacked against its predecessors. There’s a legitimate humanitarian crisis to avert, and the Kurds would likely make effective use of American military aid in its fight against ISIS extremists. Nevertheless, after years of skepticism over the projection of U.S. military force, we seem to be having ourselves an interventionist revival.

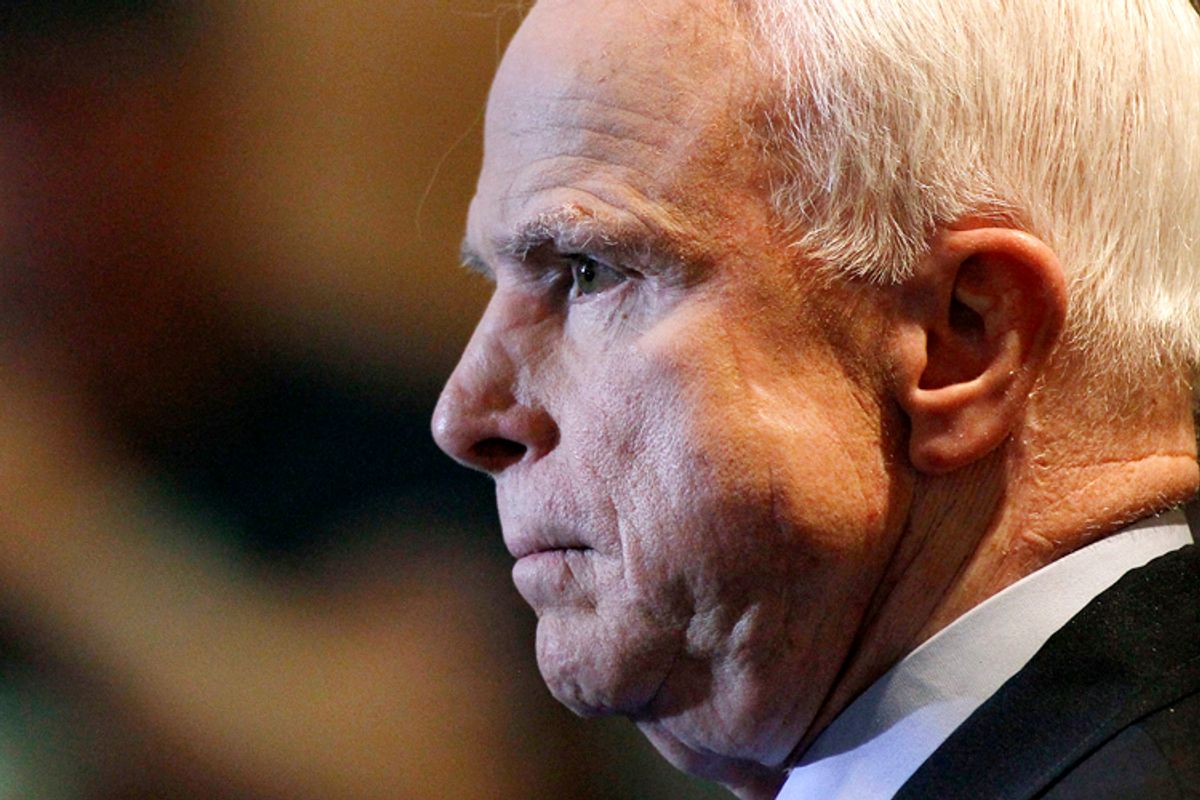

Hawks like John McCain, who’ve yet to discover a conflict that can’t be best remedied with American-made high explosives, obviously consider our limited military commitment to Iraq to be a good thing. But he wants everyone to believe that it’s still bad news, because he always wants more. And there will always be people ready to sit people like McCain in front of a television camera and let him expound on the need for America to fix the Middle East at gunpoint.

“Three airstrikes,” McCain complained on CNN’s “State of the Union” this past Sunday. “One taking out a Howitzer, and I'm not sure what the other two did. Meanwhile, ISIS continues to surround these people. ISIS continues to make gains in Syria, destabilizing Lebanon and Jordan, even into Turkey.” What would John McCain suggest we do? More bombs, more countries, more weapons flowing into the region. “I would be launching airstrikes not only in Iraq, but in Syria against ISIS,” McCain said. “And I would be giving assistance to the Syrian -- the Free Syrian Army, which is on the ropes right now because we failed to help them.”

You might be saying that John McCain always calls for things to be blown up and always goes on the Sunday shows – and you’d be right. But the political pull of interventionism is being felt in some odd corners.

Rand Paul, whose 2016 ambitions are viewed as the great hope for libertarianism’s political future, has not been shy in the past about voicing skepticism of U.S. military power. “Some in my party have distorted the belief of peace through strength into the misguided belief that we should project strength through war,” he said in June. So where does this would-be U.S. president stand now that U.S. bombs are falling on Iraq? “I have mixed feelings about it,” Paul said on Monday. “I’m not saying I’m completely opposed to helping with arms or maybe even bombing, but I am concerned that ISIS is big and powerful because we protected them in Syria for a year.” Rand has been unabashed about shedding and denying his libertarian roots as he moves closer to a presidential run, so it’s not inconceivable that he could be going wobbly on his much-derided (among Republicans) “isolationism.”

And then there’s Hillary Clinton, who reminded us all this week that she’s still very much a hawk on foreign policy when she talked to the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg about the “failure to help build up a credible fighting force of the people who were the originators of the protests against” Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

The political ramifications of Clinton’s interview are getting the most attention. She’s very likely running for president in 2016, and her own foreign policy views are unmistakably distinct from those of her party’s sitting president. As Ezra Klein and others have pointed out, Clinton’s generally more hawkish take on national security hasn’t really changed since 2008, and is probably even more out of step with the Democratic Party today than it was back then.

Less remarked upon is the question of whether arming the Syrian rebels and trying to build “a credible fighting force of the people who were the originators of the protests against Assad” would have done any good. Writing for the Washington Post, political science professor and Middle East expert Marc Lynch argues the case that arming the rebels in 2012 wouldn’t have made a difference, owing to the fragmentation of the anti-Assad forces backing the Free Syrian Army.

Clinton herself provided an answer to that question in the Atlantic interview: I don’t know. “I can’t sit here today and say that if we had done what I recommended … that we’d be in a demonstrably different place,” she said. That’s an honest answer, and light-years away from the macho bravado that led some Bush administration officials to predict a neat and tidy weeks-long military excursion in Iraq. And obviously the political sensitivities at play won’t allow Clinton to say outright that her policy would have definitely produced a better outcome. But still, it’s jarring to see a political leader argue for sustained U.S. intervention in a regional conflict and then shrug her shoulders when asked if it would have worked.

But that’s the beauty of being a hawk on foreign policy – the mere act of calling for intervention is what makes you “tough” on national defense. The outcome of that intervention doesn’t really factor into the equation. Nor do the sentiments of the American public, which is deeply opposed to involvement in Syria, and conflicted on Iraq given that we’re torn between a sense of responsibility for the chaos over there and an aversion to any further involvement. The political class will always treat the willingness to commit American men and materiel to overseas conflicts with respect because they think it means you’re “serious” about national security. And that means we’ll always be tilting toward interventionism.

Shares