On July 9, my cousin, an unarmed black man, was shot and killed by an off-duty police officer. But I don’t want to tell you about him or the incident that ended his life. I’m afraid that if I did, you would focus on his individual story when you should really focus on an institutional crisis.

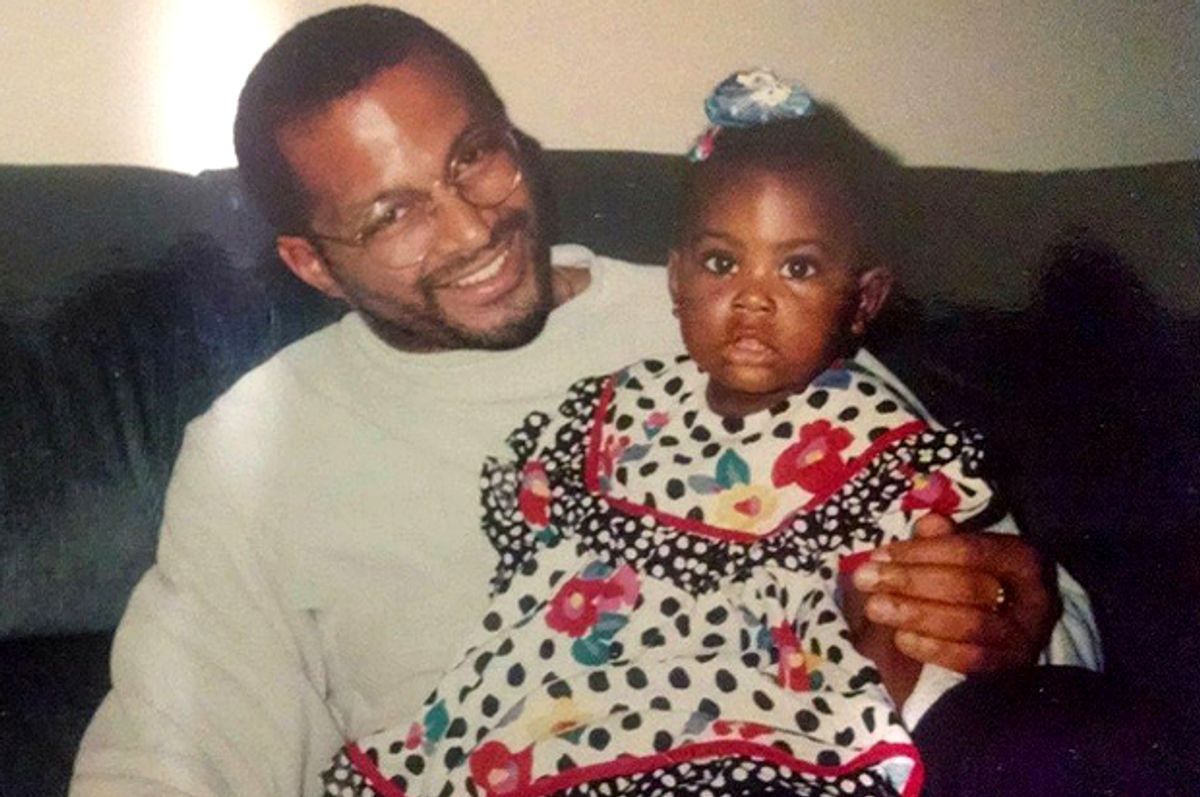

I don’t want to tell you that my cousin’s name was Charles Goodridge, that he was 53, or anything else to humanize him because then you might think that other victims are less human than he was. They aren’t.

I don’t want to tell you that he was a college graduate, that he worked in information technology for decades, or anything else to convince you that he was a “productive” member of society. If I did, you might think that other unarmed, nonthreatening black people who die like he did deserve their fate. They don’t.

I don’t want to tell you about the pain that his daughter, his brother or his mother are feeling because that might make you think that my family’s pain is uncommon. It’s not.

According to the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, 313 black people were killed by “police and a small number of security guards and self-appointed vigilantes” in 2012. One every 28 hours. Black families experience this pain every day.

I don’t want to tell you about the police officer who killed my cousin because then you might think that he is the problem. He is a problem, but he is not the problem.

We act like people who commit acts of racial violence are just a few bad apples. But we often fail to identify and fight institutions and policies that empower and encourage these people to systematically overstep boundaries. If a tree keeps producing bad apples, something is wrong with the tree, not just the apples.

I don’t want to tell you about local authorities’ lack of interest in punishing the man who killed my cousin because you might think that punishing him would be justice. It wouldn’t.

A just world would be one in which black people are not more likely to be unemployed, poor, attend underfunded schools, or packed into prisons. A just world would be one in which black people don’t need to worry about being killed for no reason. It will take much more to produce that kind of justice than punishing one man.

I don’t want to tell you that the media ignored my cousin’s killing because that might suggest that the media usually pays attention to black death. They don’t.

Examples of racial violence that receive special attention are usually the most shocking, the ones caught on video, or the ones that spark community outrage. But most cases, like my cousin’s, are barely noticed at all.

I don’t want to tell you that my cousin was killed in Texas because then you might think that black people aren’t dying all over America. We are.

I don’t want to tell you my cousin’s story because I want you to fight, but I want you to fight the right battle.

To be sure, we must fight. Even after high-profile instances of racial violence, criminal charges are often only filed after intense public protest and scrutiny. When we are active and organized, we force the powers that be to do their jobs. Without organized pressure, these incidents can be swept under the rug.

But I don’t want to tell you about my cousin because you might just fight to hold one individual accountable instead of fighting for systemic change. We can’t afford to treat cases like my cousin’s as isolated incidents.

Campaigns for justice in individual cases have been unable to address large-scale, institutional injustices, including injustices within the criminal justice system. The cries of “Justice for Trayvon” got George Zimmerman arrested and prosecuted. But they did not get him convicted and, perhaps most important, they did not transform society in such a way that would protect the hundreds of black people who have been killed in similar ways since Trayvon.

Cases like my cousin’s are significant because they are symbols of broader systemic violence. Mass incarceration, the destruction of the public school system, the widening gap between rich and poor, and many other processes are also killing black people. They are more subtle and gradual than a hail of gunfire, but they are just as deadly.

Too often we get caught up in the individual tragedy and not the environment that created it. I don’t want to tell you about my cousin because I want that to change.

Shares