If you want to see how the world really works, watch a tragedy unfold on Facebook.

What critics say about the social network is oftentimes accurate: It can be nasty and brutish, chaotic and dim, full of terrible information and the rankest expressions of ignorance. This is especially true in the case of tragedies as their full dimensions are just starting to come into focus: Ferguson. Gaza. Sanford. Isla Vista. People share without thinking, then stake untenable positions with the appearance of adamantine resolve, showing little or no compunction about inflaming their friends, family members, co-workers, neighbors, acquaintances and even the completest of strangers. The combustible mixture of social media, ego, politics and pride can turn even minor disputes into epic conflagrations. Basically it's civilization, but in miniature.

There is, however, a flip side to this equation -- another way in which tragedy finds new-media expression -- and it's actually just as revealing.

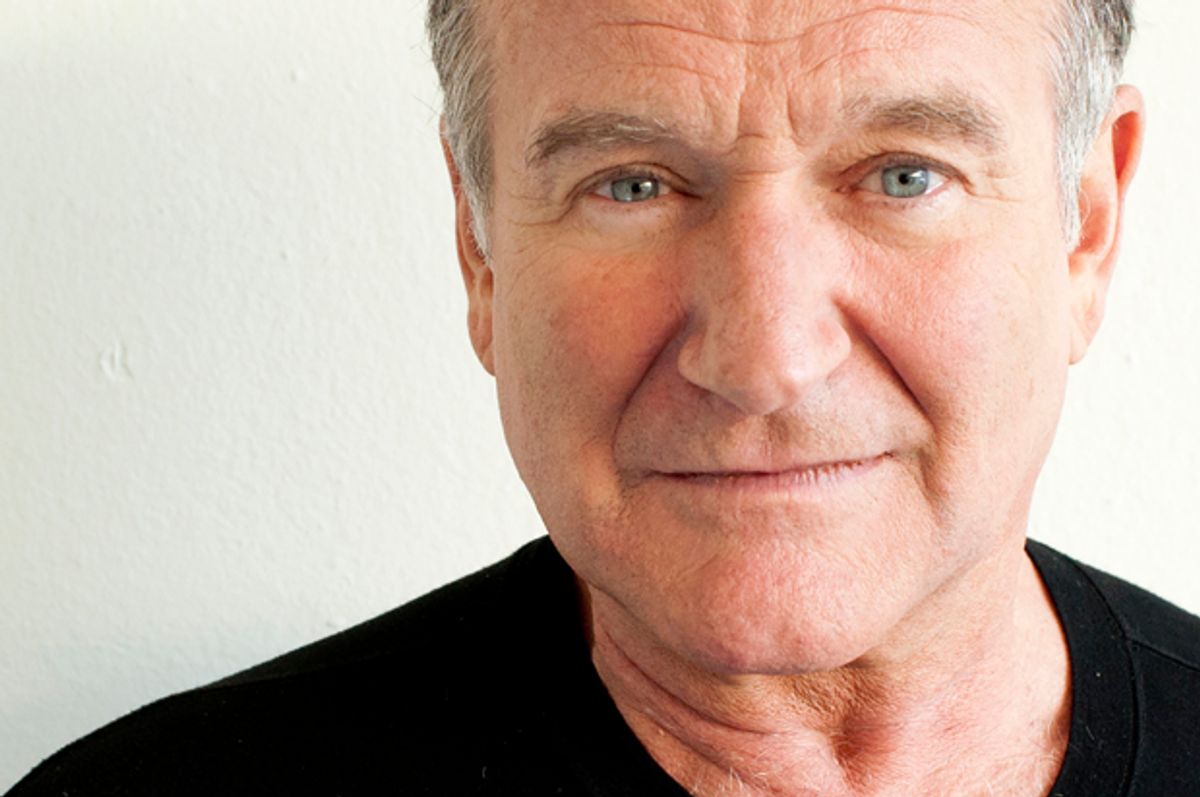

The news last week of Robin Williams' death occasioned a massive outpouring of public grief. Within moments of hearing the terrible news, millions flocked to social media to post their own personal remembrances of the beloved actor. In place of the normal vicissitudes of Facebook and Twitter, a rare consensus was established of the type we rarely ever see -- except when someone famous dies uncontroversially.

It would have been easy to take this all at face value and leave the psychology of these displays unexplored; thankfully, that wasn't the case. For every action on the Internet, there is bound to be a reaction (especially in the media world, where the well-time rebuttal is its own form of cultural capital). And the reaction to the glut of Robin Williams tributes, just like similar reactions after tragedies past, says an awful lot about where our heads are at, collectively -- both by being right, and also by being incredibly wrong.

As tends to happen these days when a famous person passes away, once the rush of memorials reached a certain critical mass last week, a minority consensus began to emerge -- that many, if not most, of those individuals professing heartbreak were not doing so in full earnestness. There was, this argument goes, an element of vulgar performance.

Some critics contended that the displays of mourning were actually lazy and inadequate -- "homogenized grief," as this widely shared Clickhole article put it. Others, like Vanity Fair's Richard Lawson, suggested darker ulterior motives:

[embedtweet id="499401194528575488"]

Politico's Dylan Byers, meanwhile, explained his own frustrations thusly:

At times, it can seem like people are trying to out-sad one another. Allow me to let you know how devastated I am about this person I never met. Allow me to tell you what my favorite films were. Allow me to share my favorite quote. — You have to imagine that the people who are truly grieving over said individual's death do not, in those first minutes, think to take to their Twitter accounts. The stream of personal remembrances reminds you of social media's true raison d'être, and throws it into sharp relief: Every post, every tweet, every click is ultimately about you.

On the one hand, there are plenty of obvious reasons why Williams' death hits hard. He was a special performer. More than that, the circumstances of his death understandably strike a chord for people who have experienced in one way or another the struggles of clinical depression. But I will admit that on some level, there's an appeal to Byers' contentions nonetheless: There is something of the rote and derivative in much of the mourning we've seen.

Honest question: How much could "Dead Poet's Society" really have changed your life, Internet? As much as plain-old empathy could explain the outpouring of grief over Williams last week, it doesn't totally explain why people have been trying to stake ownership of his work in the process.

So for what it's worth, I think Byers is partly right: It is about us, and it always has been, every time we take to social media to grieve a beloved figure. But his hypothesis is also incomplete. Left unmentioned is the biggest question of all:

Why, exactly, are we making it about us?

An earlier attempt at answering this question was made in a 2011 Washington Post article by Monica Hesse. At the time of its writing, several prominent figures -- Donna Summer, Maurice Sendak, Beastie Boy Adam Yauch, among others -- had all just died in quick succession, resulting in an unusually intense period of Internet shiva-sitting.

Hesse interviewed experimental psychologist Spee Kosloff, who identified the resulting memorials as the manifestation of a phenomenon called "Basking in Reflected Glory," or BIRG:

“Celebrities are symbols,” Kosloff says. Symbols of fame, wealth, uniqueness, good hair. “By our association with them, we can BIRG and gain a feeling of cosmic specialness.” When they die, the specialness disappears, so we cling however we can — reminding everyone that we identified with them, understood their writing, listened to the B-side more than all the other Twidiots out there. “It’s inflating your own personal tie to the thing that makes you exceptional.”

There is a certain amount of logic here. And it explains all the trying to take credit for appreciating Williams' work. But Byers' and Hesse's arguments smack a little too strongly of condescension, and their mutual insinuation -- that the memorials are just acts of emotional opportunism -- is a claim that rings especially false.

Dr. Charles Figley is an associate dean at Tulane University, and an expert in disaster mental health affiliated with the American Psychological Association. When I asked Figley about the charges of selfishness, he acknowledged the influence of our egos in the grieving process, but was unconvinced that the calculation was as cynical as Hesse and Byers suggest.

What we're really trying to do by staking ownership in the departed isn't just bolster our esteem. We're trying to solve a problem. In one sense, it's the same problem we're trying to solve when we're coaxed into those aforementioned conflagrations with people who disagree with us on matters of ideology or politics or art, contradicting the things we feel to our cores.

That problem -- which may seem obvious, but always seems to go unexamined in periods of mourning -- is our overwhelming and underexplored anxiety. "That's the whole thing about grief," Figley explained. "It's really a masking of our own fear of reality."

The simple answer: "It's about our fear of death."

* * *

In his Washington Post interview, Spee Kosloff identified the symbolic power of celebrities, and the dissonance that arises when they die, as a central factor in such grief. But once we arrive at the conclusion that it's our fear of death that motivates the creation of those symbols, it's hard not to talk about one guy in particular: cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker.

In 1973, Becker published his most famous work, "The Denial of Death." The book was heralded upon its release as a landmark text, and won Becker the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction. While it still commands respect even today -- comedian Marc Maron is a notable proponent -- the book actually made its most explicit cultural footprint a few years after its original publication, when a nebbishy Woody Allen lookalike, foisting "The Denial of Death" on his reluctant new girlfriend, Annie, expounded his Becker-informed and death-obsessed philosophy:

"Life," he said, "is divided up into the horrible and the miserable."

That philosophy is actually a major focus of "The Denial of Death," which contains as its primary insight this searing idea: that the refusal to accept our mortality -- a fundamental but nearly invisible pathology, baked right into the human condition -- is the literal cause of all evil in the world.

While you can pick bones with Becker's unapologetically bleak worldview (or also with my massively simplified version of such), it's hard to deny him the basics. A cursory look at the world around us gives the very strong impression of a civilization in the thrall of death-panic. And anyone who's ever attempted to intuit the (essentially unintuitable) depths of mortality can probably find merit in this key Becker passage:

This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression—and with all this yet to die.

Our first line of defense against the specter of mortality is to straight-up pretend it doesn't exist. And when that doesn't work -- because how could it? -- we go to more elaborate lengths to ease our trembling psyches. In particular, Becker contends, we fashion "hero systems" for ourselves, and fill them with heroic avatars -- famous people for one, but also ideas, like religion or nationalism -- which you might recognize as those "symbols" that Kosloff was talking about earlier.

Because of the exceptional qualities we've invested in these heroes and ideologies, they seem to defy the very idea of death. But this impulse to invest heroic, nearly deific properties in our leaders and social structures is a double-edged sword, Becker argues. While they might salve our creeping sense of existential dread, they can also lead to all sorts of calamitous problems: inequality, prejudice, violence -- even war. (See: nationalism.)

The degree to which this is true is beside the point for our purposes. Look around and you'll see plenty of anecdotal data to support the idea that our worldviews are informed by a yearning to outstrip our material circumstances. Viewed in that context, it's not hard to see that what inspires our attraction to celebrities -- like the singular comedic talent of someone like Robin Williams, or the credulity-straining acrobatics of professional athletes -- actually comes from the same place as our attraction to something like ideology. Both promise, Becker argues, a sense of reality that transcends the limits of death.

What we saw then last week in the mourning of Williams isn't a phenomenon unique to social media at all. It actually spans all of history. While you might be able to explain away the pyramids as a dynastic vanity project, it's harder to account for those portions of the historical record that document widespread grief at the passing of a king or a president. These emotions have been a linchpin of state power from the time of Caesar -- if much expedited in the Westphalian era by the introduction of mass communication.

This grief is as old as civilization, buried in the dense coils of our recursive minds.

No, Robin Williams wasn't a king. But he did command respect, and adoration, and even love from his fans. More important, he's always been there, if not center-stage then milling around the periphery of our cultural consciousness for the better part of four decades. At his heights he was one of our most celebrated cultural heroes. For millennials, as my colleague Dan D'Addario pointed out last week, he occupied a place in the pop cultural pantheon. His once-automatic presence in our lives makes his absence now incongruous with our sense of the world.

That dissonance is felt any time a person dies. When it's someone we knew personally, it's easy to ignore the dread. There is, after all, a perfectly rational explanation for our sorrow, and one that isn't so difficult to broach. But when we didn't know the person -- when it's Robin Williams, for example -- we're left grasping for a palatable explanation for the sickness we feel: It's because we loved his movies. It's because they touched us deeply. It's because he meant so much to us. He changed our lives.

Never mind if that's actually the case.

Public grief has always been a clumsy thing -- hackneyed and sentimental maybe, or unartfully expressed, sometimes even giving the impression of selfishness. But ultimately, it's visceral and sincere , if not often entirely honest.

We're all terrified of death, but no one wants or knows how to talk about it. That terror bubbles to the surface at moments like these, after a national tragedy, or the death of a celebrity; but it's almost always sublimated into a form -- what some might call "homogenized grief" -- that's more manageable, less queasy-making, easier than the truth to articulate and explain away. We try to rationalize our feelings through the safety of boilerplate lamentations, because the alternative -- to accept that we're scared shitless by the fact of our contingent nature, that we too will someday expire -- is too to hard to internalize, much less accept.

"Try this experiment," Dr. Figley suggests. "As you talk to someone, shift the subject to death and watch the loss of eye contact. Like any subject that is rarely discussed in depth, it is highly variable depending on the level of trust when discussed." So, for once, let's be honest and trust each other.

I'll begin:

Something I don't like to admit about myself, except in the company of very close and trusted relations, is that over the past few years I have become increasingly obsessed with the prospect of death, and regularly consumed by the terror of it.

As the influence of my parents' Catholicism has ebbed over time and drifted into the resignation of a mostly unspoken atheism, the gravity of that change has slowly come into focus: Someday I will be dead, and my subjective self lost forever. That same fact holds true for all of us, and eventually for the prospect for any life, anywhere. Over time, the universe will eventually rend itself apart, piece by piece, one final prolonged act of atomic torsion borne out over the course of eons. When all is said and done, we won't just be gone; any trace of us will as well.

But we're still here now. We still need to live with one another. And we're leaving our greatest anxieties unacknowledged, only revealing them under duress, or in the anodyne remembrances of people we never knew, but whose absence we nonetheless feel silently shattered by.

Honesty about our death-obsessed station in life means more than just understanding on an intellectual level why it might be. It means giving words to it, letting it breathe, relinquishing the control we think we have over the idea when it's sequestered in the back of our brains.

"It is the disguise of panic that makes us live in ugliness," Ernest Becker wrote in his book, "and not the natural animal wallowing."

So let's talk.

Shares