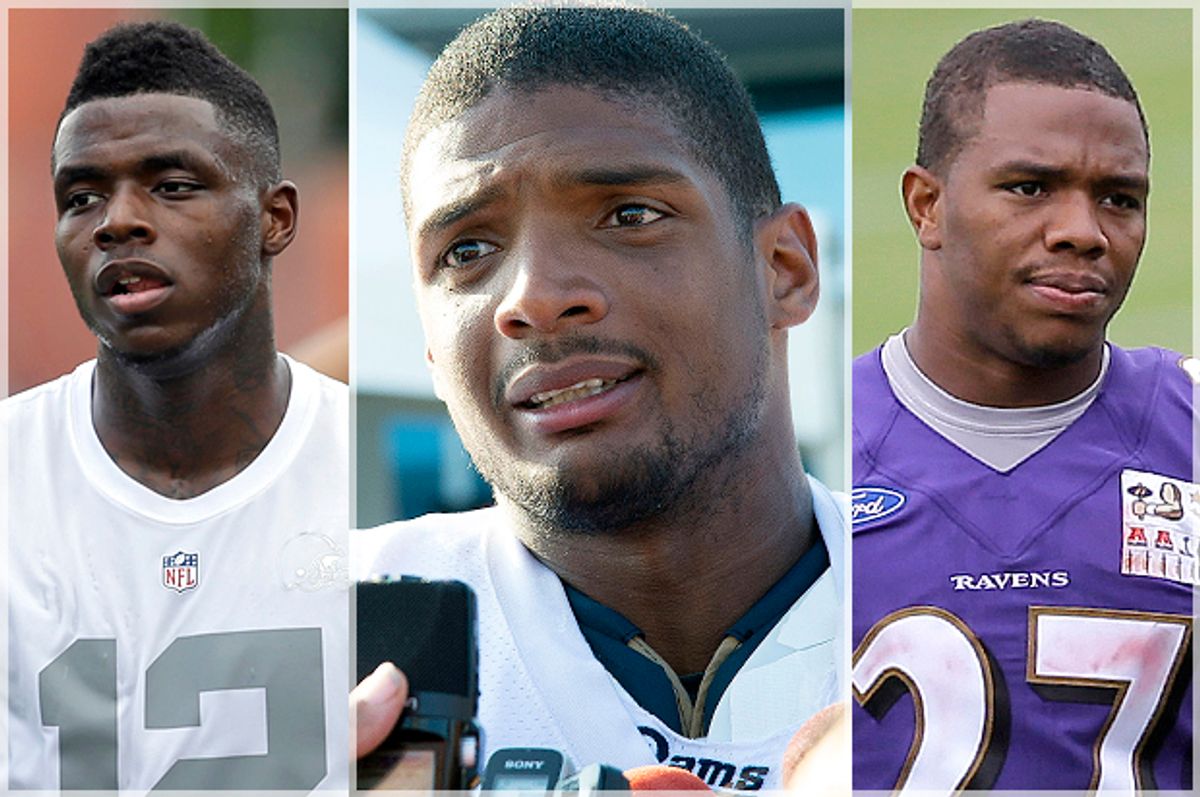

On Wednesday, the NFL upheld Cleveland Browns wide receiver Josh Gordon's full-year suspension, benching him for the entire 2014 season and possibly the 2015 training camp because of a failed drug test. He appealed. It didn't work. And now Gordon is out for 16 games because he smoked pot (or was around someone who smoked pot). Compare this to the two-game suspension Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice received after he allegedly assaulted his partner so viciously that she was knocked unconscious. Compare it to the five-game suspension Tennessee Titans linebacker Albert Haynesworth received after he stomped on another player's unhelmeted head and scraped his cleats across the man's face. Compare the NFL's long-standing comfort with all manner of violence to its brow-furrowing about whether an openly gay player would be a "distraction" on the field.

Then ask yourself if the NFL has a morality problem.

"The NFL's attitudes about drugs, gender and sexuality haven't caught up with the realities of America in 2014," Steve Almond, essayist and author of "Against Football," told Salon. "So they have a morality, it's just a morality that's pre-1950s and possibly going back to the 1850s when it comes to gender roles."

Marijuana is now legal in two states and decriminalized in several others. Cultural attitudes about pot as a recreational drug are shifting, and so is the landscape around its use in medicine. But the NFL's collective bargaining agreement, which determines the kind of punishments meted out for drug use, is as punitive as ever. In the wake of the votes that legalized pot in Washington and Colorado, NFL spokesman Greg Aiello made it clear that the NFL's position wasn't changing. “The NFL’s policy is collectively bargained and will continue to apply in the same manner it has for decades," he told USA Today. "Marijuana remains prohibited under the NFL substance abuse program."

Beyond recreational pot use being a pretty normal part of life for many Americans, plenty of players use marijuana as a safer, less addictive alternative to painkillers and alcohol. "These guys are in pain an incredible amount of the time," Almond said of players' use of pot to self-medicate. "This game requires them to constantly be injured. In order to keep their jobs, they have to mask those injuries. Usually with insane amounts of drugs -- some obtained legally, and others, undoubtedly, obtained illegally."

"Drugs have become a major P.R. issue for the NFL," Jessica Luther, a journalist and sports writer currently working on a book about college football and sexual assault, told Salon. "If and when the NFL does get around to doing something about domestic violence, it will be because of the bad P.R. it received around Ray Rice." Luther's words would turn out to be prescient. Less than 24 hours after we spoke, the NFL announced that the penalties for domestic violence had been steepened to a minimum of six games for a first offense and banishment over a second offense.

Now it's a fair question about whether a six-game suspension will bring more justice when the greater message from the league has been one of permissiveness around violence against women, but NFL commissioner Roger Goodell's letter also included a number of new policies aimed at preventing violence, rather than just punishing it. This is, perhaps, a more transformative move than just becoming more punitive about domestic violence offenses. After the release of the video of what appears to be Rice dragging his partner's unconscious body out of an elevator, Ravens coach John Harbaugh said he hadn't seen anything that would make him think the team's running back wouldn't return to the field. Imposing a six-game suspension on players may not correct that kind of thinking among league officials, but proactive education and other preventative measures, new priorities according to the letter, just might. But all of this, of course, depends on how seriously the NFL takes its new commitments.

Clearly, the bigger question is one of league culture. What the NFL will tolerate, and what it will not. What will change moving forward, and what won't. When Michael Sam was drafted by the St. Louis Rams, some NFL executives spoke (on condition of anonymity, naturally) of how his presence in the locker room would be disruptive. Earlier this week, ESPN reported on the defensive end's showering habits as though it was legitimate news. Contrast this handwringing about an out player's bathing routine to its history of permissiveness and silence around violence against women, and the NFL's bizarre moral calculus becomes clear.

"To think Sam is disruptive while Rice is not is the direct result of a whole lot of men being in charge of a whole lot of men," Luther said of the league's priorities. It's a problem she believes can be resolved, at least in part, by sustained pressure from fans -- and bringing more women into the NFL's ranks. "I can't imagine that the Ravens' social media campaign defending Ray Rice would have looked the same if there had been women involved."

Almond also sees change as coming from outside the NFL: "If you are disgusted by the abject hypocrisy of suspending a guy for a year because he smoked some pot when another guy gets two games after he allegedly knocked his then-fiancée unconscious, then don't give it your money." Or protest loudly, it seems. Goodell made good on his promise to take action on domestic and sexual violence only after fans and the public demanded change.

The NFL will only move where we're willing to push it. Both Luther and Almond agree these problems are bigger than just the NFL. Its warped view of drug use, its tolerance for homophobia and violence against women isn't some aberration -- it's us, basically. "These are broader American pathologies," Almond said. "This is America being ass-backwards; the NFL is just a particularly flagrant example of it."

Shares