Bruce Levenson, the controlling owner of the Atlanta Hawks basketball franchise, has announced plans to sell his interest in the team after self-reporting an email from 2012 in which he characterized Hawks games as “too black,” and lamented that black fans had “scared away the whites.” He wanted the Hawks to figure out a way to create an environment more comfortable and conducive to white participants, since white participants, particularly the “35-55 white males” have more of an economic base to support the franchise.

Reading Levenson’s email is a study in racial contradictions and a clear example of our need for more sophisticated frameworks for thinking about racism in the 21st century. When I read Levenson’s public statement and his choice to self-report his email before being exposed, his comments seemed to have a certain level of integrity and forethought. He characterized his own ramblings in the email as “inflammatory nonsense” and acknowledged that “as a leader,” his role is to “challenge” rather than “validate or accommodate” racial “biases or preconceptions.” Having now read his email, I think it provides us an opportunity to have an honest set of conversations about the way that racial demographics impact business.

In other words, I don’t think Levenson is a rabid racist. He is no Donald Sterling. In fact, he seems well aware of the operations of racial bias and the ways that these biases inform perceptions of Atlanta Hawks events as being “too black.”

For instance, he writes, “My theory is that the black crowd scared away the whites and there are simply not enough affluent black fans to build a significant season ticket base. Please don’t get me wrong. There was nothing threatening going on in the arena back then. I never felt uncomfortable, but I think southern whites simply were not comfortable being in an arena or at a bar where they were in the minority. On fan sites I would read comments about how dangerous it is around Philips yet in our 9 years, I don’t know of a mugging or even a pick pocket incident. This was just racist garbage. When I hear some people saying the arena is in the wrong place I think it is code for there are too many blacks at the games.”

He even acknowledges that the lack of revenue generated by black fans on auxiliary merchandise at games is because “black fans don’t have the spendable income.” I think it is fair to say that many black people do have less disposable income than the average white male, aged 35-55.

When I read these words, I see a businessman attempting a conversation with colleagues to make sense of the cultural demographics shaping Hawks basketball. To be clear, the desire that Levenson expresses for Hawks games to be more white, his assertions that the “kiss cam is too black” and the music needs to be “familiar to a 40 year old white guy if that’s our season tix demo” is all troubling. What does it mean for something to be “too black”? Moreover, what does it mean to advocate for an erasure of activities at the games that appeal to a large and paying African-American fan base, in order to be more accommodating to potential white patrons? We still live in a world where the logic of integration seems impossible. In order to make space for white patrons, black patrons will experience a reduction of their participation in fun crowd activities like being featured on the kiss cam or being chosen for shooting contests. In this regard, it is whiteness, and the inability of whiteness to coexist alongside blackness, that is the problem.

Though Levenson seems aware of the racism of this kind of stance at some level, his attempt to diversify the Atlanta Hawks’ fan base falls victim to the very kinds of critiques of racism that he himself makes. He recognizes and characterizes as racist arguments from white people about Philips Arena being dangerous. He recognizes that the invocation of these ideas of threat are “code for too many blacks at the games.” However, what he wants are more white people to attend games, so he concedes that the sporting events are too black. It makes far more sense to expect that because Atlanta is a majority black city, the racial demographics of fans at its also majority black NBA team’s games will be majority black. Instead, Levenson aspires to a world more similar to a place like Washington, D.C., where he notes that “even DC with its affluent black community never has more than 15pct black audience.” To me, that is a place for questions not aspirations.

That Levenson has a fairly high level of clarity about the way many white people encode racist demands in non-racial language is deeply insightful, and that makes his solution incredibly disappointing. But his solution is a result of misframing the blackness of Atlanta Hawks events as the problem.

Unfortunately, I don’t think there is much to be gained by having Levenson sell his share of the Hawks. Because we continue to be deeply dishonest about race, it is easy to make Levenson a sacrificial lamb in a morality play in which every person who tries to speak forthrightly about race is automatically racist. In this case, calling out Levenson’s problematic racial assumptions and creating programming and solutions to diversify his demographics without blaming or penalizing black fans is a more appropriate course of action.

But an unfortunate and perverse consequence of Donald Sterling’s massive profits from the sale of the L.A. Clippers is that admitting one’s racism is profitable. Thus white men profit from saying and doing racist things, while organizations like the NBA get to claim that they are taking strong stances against racism in the league. But ferreting out individual racists will never solve the problem of systemic racism. It simply makes everyone feel better.

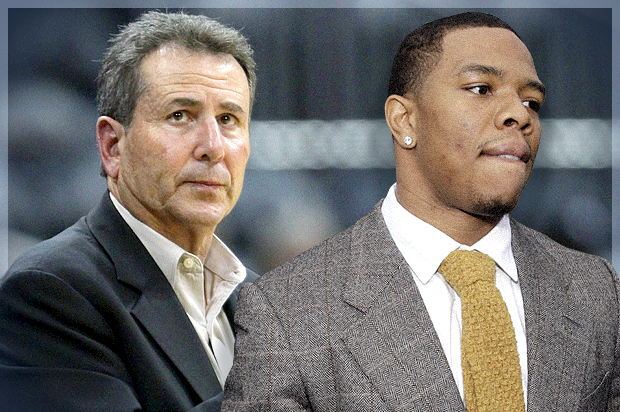

Similarly problematic thinking is evident in the Baltimore Ravens’ decision to terminate Ray Rice’s contract and the NFL’s decision to suspend him indefinitely after TMZ leaked video of his vicious attack on now-wife Janay Rice Palmer yesterday. First, the NFL is no stranger to domestic violence disputes. A recent memorable incident was the murder-suicide of Kansas City Chiefs player Jovan Belcher against his partner Kasandra Perkins in late 2012. Second, the fact that Rice received only a two-game suspension until this video surfaced suggests that the league is more concerned with the optics of Ray Rice knocking Janay Palmer unconscious than addressing the ways that the hypermasculinity of sport perpetuates a culture of violence toward women. By taking such a hard-line, if belated, stand against Rice’s actions, the NFL now appears responsive to the problem of domestic violence, although it has made no promises to implement any kind of consistent anti-violence training for NFL players. It has simply ferreted out Ray Rice as an ultimate offender and benched him until further notice. This strategy won’t make Janay Palmer’s life safer and it won’t help the current partners of players who are being abused in secret.

We should be concerned about living in a culture where we routinely disbelieve victims of racism, sexism or domestic violence unless there is video or audio evidence. When we acknowledge the pervasiveness of violence, and of racism and sexism, we will be more responsive to victims and less committed to the kind of dishonesty that greets “isolated” incident after “isolated” incident with shock and surprise.

In the case of the Hawks, however, Levenson will not ultimately lose, and the Atlanta Hawks will not ultimately gain. But our national ability to have productive conversations about the difference between racially problematic attitudes and practices and rabid racism of the sort that demands our highest censure and response will continue to falter.