Travel south along Route 69 out of Kansas City for about forty miles and you will reach LaCygne Lake, an otherwise scenic reservoir overshadowed by the coal-fired Kansas City Power & Light electrical power plant that sits on its eastern shore. From there, if you head west along Route 152, you will soon arrive in LaCygne proper, “the City of the Swan on the Marais des Cygnes.” A city in name only, LaCygne is home to just 1,200 people, many of whom work at the nearby power plant. Most of those who do not work for KCP&L work the land — this is farm country. Sparse herds of livestock graze across swaths of land sectioned off by rickety wooden fences, and small barns and farmhouses stand alone against the vast, empty sky.

Travel south along Route 69 out of Kansas City for about forty miles and you will reach LaCygne Lake, an otherwise scenic reservoir overshadowed by the coal-fired Kansas City Power & Light electrical power plant that sits on its eastern shore. From there, if you head west along Route 152, you will soon arrive in LaCygne proper, “the City of the Swan on the Marais des Cygnes.” A city in name only, LaCygne is home to just 1,200 people, many of whom work at the nearby power plant. Most of those who do not work for KCP&L work the land — this is farm country. Sparse herds of livestock graze across swaths of land sectioned off by rickety wooden fences, and small barns and farmhouses stand alone against the vast, empty sky.

Not all of LaCygne’s residents are farmers, and not all of them can afford farmhouses. Dilapidated trailers and mobile homes are a common sight in this part of rural Kansas. Many of them sit in isolation amid acres of unused, desolate scrubland. On June 2, 2000, Kansas law enforcement officials executed a search warrant on one such trailer belonging to John Edward Robinson of Olathe. During the course of this search, police discovered the bodies of Izabela Lewicka and Suzette Trouten, both of which were stuffed inside 85-pound chemical drums stacked outside the derelict trailer.

Shortly after the discovery of Lewicka and Trouten’s remains, police searched Robinson’s Olathe home, and two garages he had been renting at a storage facility in Raymore, Missouri, a short distance from the Kansas/Missouri state line. At the garages, law enforcement officials discovered the body of Beverly Bonner, along with the remains of Sheila Faith and her fifteen-year-old daughter, Debbie. All three bodies were found crammed into chemical barrels similar to those found at Robinson’s abandoned trailer in LaCygne. Robinson had covered the cement floor of the garage with cat litter to absorb the fluids slowly leaking from the drums.

Medical examiners later determined that all five women had been killed by blows to the head with a hammer or another blunt instrument. Although Robinson was eventually implicated in the murders of three additional women — Paula Godfrey, Lisa Stasi and Catherine Clampitt — their bodies have yet to be found.

Robinson later came to be known as “the Internet’s first serial killer,” as police believe he began targeting and vetting his potential victims online as early as 1993. However, Robinson is perhaps better known as “the Slavemaster,” his online handle and the moniker quickly bestowed upon him by the media shortly after his arrest. Robinson frequented BDSM bulletin boards to find his victims, and manipulated them under the pretense of dominant/submissive relationships. Before she disappeared in 1999, Izabela Lewicka signed a 115-item contract with Robinson as his submissive, granting Robinson absolute power over not only her body, but also her bank accounts. Around the time of Lewicka’s disappearance, Robinson convinced Trouten, who also self-identified as a submissive, to quit her job as a nurse and move from her native Michigan to Kansas so that she and Robinson could travel the world together. She was never seen alive again.

Robinson was sentenced to death for the murders of Lewicka and Trouten in 2002. Today, he is awaiting execution in El Dorado Correctional Facility, a maximum security prison thirty miles northeast of Wichita. Most of the evidence seized during the searches of Robinson’s home and rented storage garages remains in the possession of Kansas and Missouri law enforcement officials — but not all of it.

For just $65, you can purchase the original seventeen-page lab report conducted by the Kansas City Police Department detailing the findings of the contents of Robinson’s storage garages, the same report used by Robinson’s defense attorneys during his trial. The original search warrant for Robinson’s home at 36 Monterey Lane in Olathe is available for $125. For $150, you can buy a set of forty-six high-resolution digital crime scene photographs taken by investigators at Robinson’s land in LaCygne — images that were never released to the media and depict the decomposing bodies of Izabela Lewicka and Suzette Trouten in graphic detail. And, for $1,000, you can purchase the Santa Claus costume that Robinson wore to children’s parties, scouting events and holiday family gatherings, an essential prop in the carefully practiced small-town family man façade that Robinson maintained for years before his crimes were revealed to the world.

The personal effects of serial killers — often referred to as “murderabilia,” a term coined by Andy Kahan, director of the Crime Victims Office for the City of Houston — are prized by collectors. As with many collectibles, these items are considered more valuable, and thus more desirable, depending on their rarity and the profile of their former owners. Items that once belonged to the household names of serial killing — the Bundys and the Dahmers and the Gacys — are to murderabilia enthusiasts what Inverted Jenny postage stamps are to stamp collectors. Locks of hair, fingernail clippings, even scrapings of skin from killers’ feet have all been sold to hobbyists eager to possess their own grisly trophies. However, the murderabilia market is hardly limited to the biological. Many of the most valuable items on the market are those that serve as a record of the thoughts and feelings of notorious killers, such as letters, suicide notes, even greetings cards. Robinson penned many letters during his trial and subsequent imprisonment, including five individual suicide letters — one to each of his four children and another to his ex-wife Nancy, who divorced him after forty-one years of marriage in 2005 citing “irreconcilable differences.” Each of these suicide letters is available for purchase at a discounted price of $80.

Eric Holler is the proprietor of Serialkillersink.net, one of the best-known and most successful murderabilia outlets on the Internet, and the site from which many of Robinson’s personal effects are available. Holler, who for a time went by the pseudonym “Eric Gein” in homage to renowned killer Ed Gein, spent years corresponding with incarcerated killers and slowly amassed a considerable collection of their personal effects.

“Back in ’96 or ’97, I started writing Richard Ramirez, who was the infamous ‘Night Stalker,’” Holler says. “He responded to me right away, and he approached me to become his art dealer, to sell his art for him. I started writing other guys, and they would send me artwork and craft items. They would go to the prison barber shop to get their hair cut, and send me locks of their hair. This was the ‘90s, when eBay was all the rage, so I started putting these items up on eBay. They sold really quick and really well, and I was making good money at it real fast.”

Despite the almost overnight success of Holler’s online enterprise, changes to eBay’s internal policies soon interfered with his burgeoning business. In 2001, eBay succumbed to pressure to ban serial killer memorabilia from the site after a two-year campaign by Kahan and his supporters — a decision that Holler says had unintended consequences.

“The only thing that did was force guys like myself — and there’s a couple other guys around the country who do the same thing — it forced us to go and get our own websites,” Holler says. “That, in effect, caused this industry to gain a lot of momentum and, you know, not become mainstream, but it became more than just listings on eBay. We had our own sites. The industry took off because eBay outlawed these types of items.”

Avid collectors of murderabilia often gravitate toward mementos from a specific killer, much in the same way that record collectors search for rare LPs released by specific bands. Many of the most dedicated serial killer enthusiasts can tell you just about everything there is to know about their favorite murderers: birthday, astrological sign, family history, how they chose their prey, even minute forensic details of their crimes. However, few know what it is like to look evil in the eye. This is something that Dr. Steven Egger knows all too well.

Egger is one of the world’s most renowned criminologists. In addition to being the author of several books on serial murder, Egger has extensive experience in law enforcement, having worked as both a homicide detective and a consultant for police forces around the world. During his lengthy career, Egger worked on some of the country’s most high-profile cases, including the manhunt for Henry Lee Lucas in 1983 — the murderer who inspired John McNaughton’s 1986 film Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer — and the case of Gary Ridgway, better known as Seattle’s necrophiliac Green River Killer.

“I got together with Henry through the Texas Rangers,” Egger says. “I assisted them in tracking Henry and Ottis Toole, Henry’s transvestite partner, across the country from Texas all the way to Florida. I probably spent between thirty and forty hours with Lucas, all told.”

In Egger’s experience, serial killers tend to share many common pathologies, including childhood abuse — experiences that Egger believes set Lucas on the path to murder long before he claimed the life of his first victim.

“He was the perfect product of what some psychiatrists have said it takes to produce a serial killer,” Egger says. “You know, exposure to true crime and true detective magazines, pornography around the house, his mother living promiscuously. She forced him to watch her have sex with her johns — she was a prostitute — and he just grew up to hate women. To him, all women were prostitutes, including his mother.”

While the pathologies of serial killers are relatively easy for Egger and other criminologists to identify, if not understand, the public’s morbid fascination with these murderers is another matter. I asked Egger why such heinous acts, and those who perpetrate them, occupy such a darkly alluring position in American culture.

“Basically, people don’t understand the motive,” Egger says. “That’s one of the things that excites them. The problem is we don’t spend enough time worrying about the victims. We spend so much time making antiheroes of the killers that we forget that these people who were killed were somebody’s husband or somebody’s son or somebody’s daughter, somebody’s wife. Public media, whether you’re talking about PBS or NBC or Fox News or any of the networks, tend to spend more time talking about the killer than they do about the victims. They might list the victims, but they don’t talk about the victimology.”

The ways in which the mainstream media frames serial killings does more than dehumanize the victims. The level of exposure devoted to the killings themselves often results in the perpetuation of negative perceptions of already marginalized groups, such as sex workers, the mentally ill, and those with sexual appetites deemed unusual or deviant, and greater social divergence between mainstream society and those living at its edges.

“I remember in the Gary Ridgway case — the Green River Killer, up in Seattle — where they did some man-on-the-street interviews, and one of the people that was being interviewed told the newscaster that the people who were killed had it coming because of what they did, because they were prostitutes — forgetting about the fact that they were human beings,” Egger says.

With the exception of certain technicalities, the acquisition and sale of murderabilia is not prohibited by law. Eight states — Alaska, California, Florida, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, Texas and Utah — forbid the sale of convicts’ personal effects if they directly profit from the sale of their belongings, under what have become known as “Son of Sam” statutes. However, families of killers’ victims can benefit from the sale of such items under specific exemptions to these laws, a clause that allowed the United States Marshals Service to auction off the former belongings of Ted Kaczynski, better known as the Unabomber, in 2011. The online auction of Kaczynski’s personal effects, including his shoes, hand tools, books, hunting arrows and a portable Corona typewriter, raised almost $233,000, which was dispersed to the families of those who died during Kaczynski’s seventeen-year letter bombing campaign that began in 1978.

Although the “Son of Sam” statutes may seem problematic for someone in Holler’s line of work, he told me that when it comes to individually bought and sold items, such as those sold through his site, law enforcement officials don’t tend to be as motivated to pursue legal action.

“The thing about those ‘Son of Sam’ statutes is that, honestly, they’re geared toward movies and book deals,” Holler explained. “You know, huge amounts of money. That started because David Berkowitz — the Son of Sam — was going to write a book.”

Holler was quick to point out that he does not pay killers for their belongings. However, he added that sometimes, the line between the personal and the professional becomes blurred. What happens when serial killers like Ramirez become more than just a livelihood?

“When these guys send me artwork and craft items, I do not pay them outright for their items — but I do help them when they need help,” Holler told me. “My opponents, of course, attack that. I’m not going to deny that I help these guys when they need help, because they are what I do for a living. They are, in effect, paying my bills. I make no qualms that I will help these guys when they need money. Say, for instance, Ramirez. He passed away, he died last year. I made alot of money off him over the years, from his artwork. I mean, he’s one of the most notorious, infamous serial killers of modern history, but I would help Ramirez with money. I would send him money when he needed it. The thing is, I’m not the only one doing that. You know, these guys — as crazy as it sounds — have followings. These guys have people that write them. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I know that people help these guys out.”

Attempts to pass an outright ban on the sale of murderabilia have failed repeatedly. Republican Senator “Big Bad John” Cornyn of Texas, one of former President George W. Bush’s most trusted cronies, has tried and failed twice to pass his Stop the Sale of Murderabilia Act, which he reintroduced to the Senate again last year with the support of Democratic Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Holler has a dim view of such legislation.

“I think it’s bullshit,” Holler says. “I mean, I have the First Amendment. I’m an American citizen — we live in America. We have the First Amendment to protect us. That’s what makes this country great. We can voice our opinions. My opponents like to blow it up; to paint a picture that the entire country is against quote-unquote ‘murderabilia,’ and that’s just not true. Those bills get shot down and don’t even make it to the floor because they have no support. I think that it’s great to be opposed to something, it’s great to be able to voice your opinion, but if murderabilia was outlawed or banned, what’s next? Adult entertainment? Interracial relationships? Firearms? Where would the line be drawn?”

Egger isn’t persuaded by claims that collectors of murderabilia are preserving artifacts of historical and cultural significance. To him, murderabilia is little more than a macabre pastime that dishonors the memory of serial killers’ victims and undermines the work of crime victim advocates. Despite the legality of the murderabilia industry, Egger cannot fathom what drives people to collect serial killers’ belongings.

“I think it’s extremely unethical and very distasteful,” Egger says. “I don’t know why anybody would want to have the hair of Henry Lee Lucas, or the dirt from John Wayne Gacy’s crawlspace where he buried his victims. These people make themselves out to be so-called collectors of the unique and unusual, but all they’re really doing is reliving the killings. I think they’re living in another reality. They don’t realize that we’re talking about real people’s deaths. It’s very difficult for these people to have any empathy for the victim, because the victim is just a number, just as the victim is to the killer. To some extent, the killer is anesthetizing the public to his own acts.”

Although the appeal of possessing the personal effects of notorious killers may be distasteful to some, true crime collectibles have become extraordinarily popular. Collectors are not limited to any one particular demographic, and Holler told me that his clientele is more diverse than one might think.

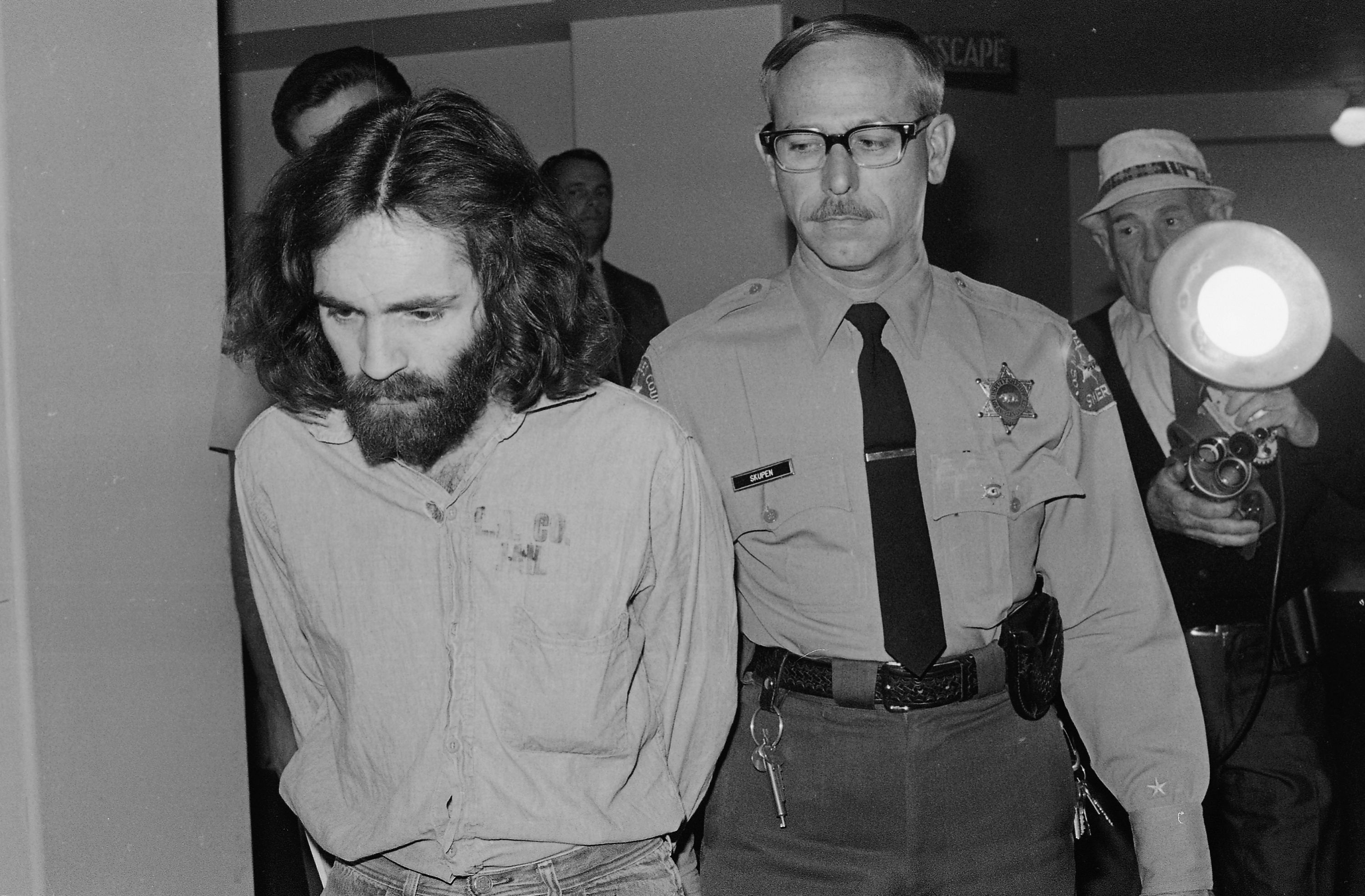

“My customer base is worldwide, and it’s vast,” Holler says. “Of course, I sell to your average twentysomething-year-old college student who’s buying a piece to put on his wall for a conversation piece. On the other hand, I sell to psychologists who buy school shooter letters from me, because they study these letters to gain a better understanding of these shooters. There’s a professor who buys from me that teaches criminal law, he buys these items to help teach classes. Men and women in our military make up a big chunk of my clientele. The old stereotype that only crazy people want a Charles Manson signature or a Charles Manson letter or whatever? That’s outdated.”

While many Americans can agree on the serious ethical dilemma of murderers profiting from their crimes at what some believe is the expense of the victims’ families’ grief, the principles of free market capitalism are sacrosanct. As long as there is public demand for these trophies, entrepreneurs like Holler will continue to supply that demand. Despite vehement vocal opposition to the murderabilia industry, it seems likely that the moral outrage of the John Cornyns and Andy Kahans across the nation will ultimately fall on deaf ears. For now, business is booming for Holler and his competitors, and it shows no signs of slowing down any time soon.

“The formula I’ve used for the past seventeen years or so has worked,” Holler says. “I’m just going to keep doing what I’m doing. I have customers who’ve bought from me for fifteen years, and every other day, I’m gaining new customers. I’ve been approached by various production studios, and there is talk of a reality series. Nothing has been signed, but there is a chance that a reality series pilot will be shot and shopped around the networks. They seem to be homing in on the murderabilia market. What I’m doing appears to be a hot property.”