It's nearly impossible to dislike Caitlin Moran's first novel, "How to Build a Girl." Moran herself is so relentlessly likable, cranking out a superhuman stream of columns and articles for British newspapers, as well as television appearances, interviews, tweets and the bestselling essay collection, "How to Be a Woman." She's witty, brassy, audacious, bawdy -- a true daughter of Chaucer's Wife of Bath -- and generally seems to have her head screwed on right. Her thoughts on just about any topic are well worth hearing.

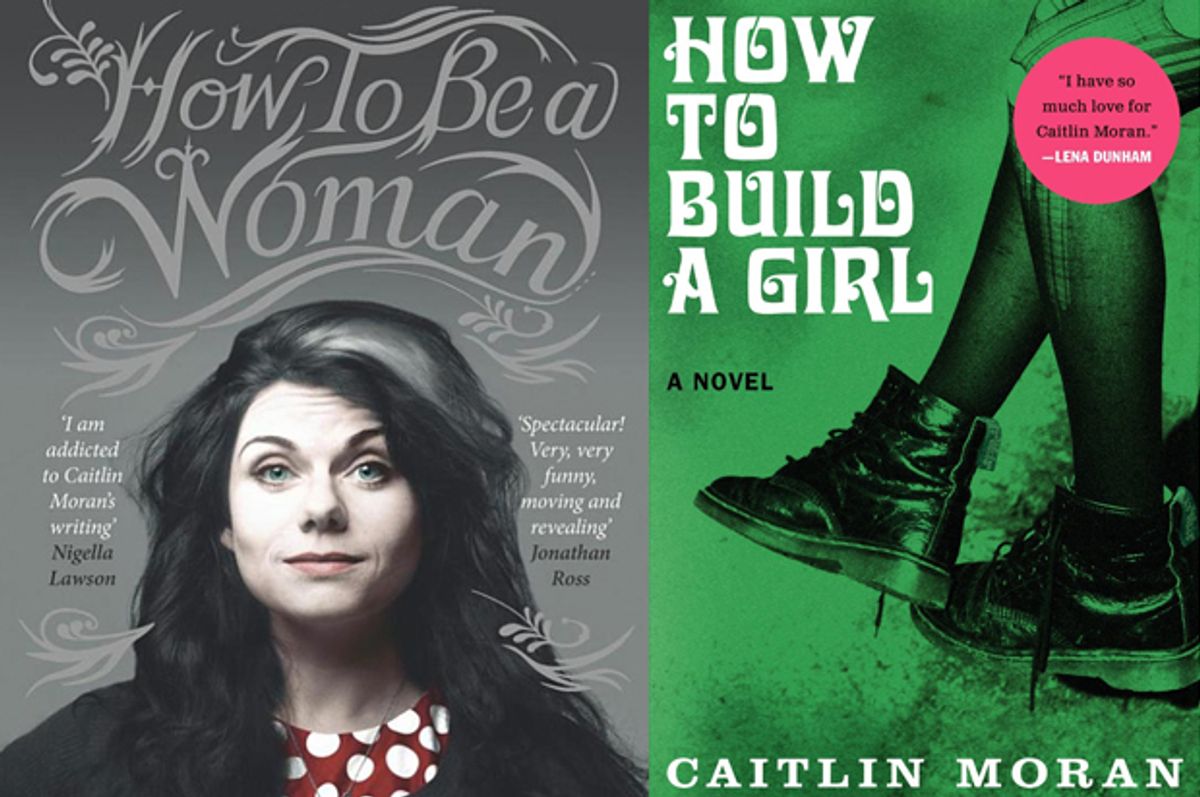

But truth be told, there's not much reason for "How to Build a Girl" to exist. Its similarity to "How to Be a Woman" extends a good way beyond its title. "Woman" is a work of autobiographical nonfiction, not exactly a memoir or life story, but a series of pieces considering various issues of young womanhood: body image, the tyranny of contemporary grooming standards, workplace sexism, pornography, the wedding industrial complex, abortion, motherhood, etc. Moran considers herself a humorist, and she approaches all of these concerns with a brisk, upbeat, profane and often very funny voice. "How to Be a Woman" is less a self-help book than a series of rallying cries designed to help Moran's readers prevent themselves from being driven nuts by the countless paradoxes and dilemmas that arise from living in a female body during the 21st century.

Moran is very, very good at this. For example, instead of meandering through such slippery, abstract concepts as "objectification," her critique of both porn and strip clubs has more to do with what she (accurately) perceives as the near-absence of female desire and pleasure in both. In her opinion, what's bad about a generation of children learning about sex from Internet porn is how seldom they will encounter "something that shows sex as something that two people do together, rather than a thing that just happens to a woman when she has to make rent. Something in which -- to put it simply -- everyone comes." Because Moran writes so frankly about her own teenage masturbatory adventures, in which she scavenged turn-ons from such unlikely sources as "An American Werewolf in London" (or, really, any Jenny Agutter vehicle), she's able to present a counterimage of positive sexuality that has some life to it.

But "How to Build a Girl" is not an essay or memoir but a novel, a work of fiction, albeit one that hews pretty closely to what Moran has revealed about her own life. Like Moran, Johanna Morrigan, the narrator of "Girl," has grown up in a housing project in the decrepit West Midlands industrial town of Wolverhampton. She comes from a big family (four siblings to Moran's seven), with a musician father on disability, an unsteady supply of food on the table and no full-length mirrors (because the whole family would rather not know). Moran has a surly-but-loyal younger sister who adores George Orwell; Johanna has a surly-but-loyal older brother who adores George Orwell. Both girls sleep in the beds their grandmothers died on. Both suffered through a fat and fairly clueless pubescence, seething with big but inchoate lusts and aspirations. Both leave school young and launch precocious careers as rock critics for one of England's fierce, haughty pop-music papers.

Although "How to Build a Girl" comes with a disclaimer announcing that Johanna's "family, colleagues, the people she meets and her experiences are not my family, the people I met or my experiences," this is pretty hard to credit. No doubt much of "Girl" is invented, but given the dozens of obvious parallels between Moran's life and Johanna's, it's impossible to tell which and this encourages the impression that the book is extensively autobiographical. This may not bother some of its readers, however. It's a strange feature of contemporary literature that readers expect memoirs to be scrupulously factual while at the same time seem to want novels to be only barely fictional. (Just listen to most interviews with fiction writers and see how often the questions tack toward a version of "Did this really happen to you?")

We've also got an unsung tradition of celebrity-written pseudo-novels. People like Nicole Richie (who published "The Truth About Diamonds," about "a rock royalty princess and a card-carrying member of Hollywood's inner circle"), Lauren Conrad ("Sweet Little Lies," about "the average girl next door" who gets her own reality show) and Snookie ("The Shore Thing," about Jersey party girl who "becomes a local celebrity overnight") produce "novels" whose main attraction is not their deft storytelling but the dish they supposedly deliver on the lives of the inexplicably famous. Labeling these books as fiction provides the authors with plausible deniability, and presumably the people who buy them believe they're getting the sort of quality dirt that no one would dare publish as nonfiction.

Moran isn't doing that -- she's got way too much intelligence and talent to pull such a stunt. But her brilliant career nevertheless speaks to the contemporary reader's desire for the unvarnished truth, rather than made-up stories about imaginary people who don't realize they're illustrating some aspect of the human condition. So why write a novel at all? The best stuff in "How to Build a Girl" is the same as the best stuff in "How to Be a Woman": the attitude, the fearless confessional honesty, the Moran persona itself, with its big heart and unabashed appetite for all of life's pleasures. She's a teller, not a shower, and her penchant for editorializing and exhorting is never absent for long from the pages of "How to Build a Girl."

By contrast, the novelistic elements in this book are slight. It's appealing that Moran sets up the expectation of a Bridget Jones-like story of a gawky girl with an embarrassing family who gets hung up on Mr. Wrong. Then, instead of making Johanna's development as a character hinge on a dawning appreciation of the right guy, Moran has the narrative turn on a revelation about her heroine's work. The self Johanna must be true to first is her writing self. This theme also gives Moran the chance to vamp on and debunk a certain school of British rock criticism, a sort of clever drivel that revels in virtuoso eviscerations of mediocre bands. Her older male colleagues encourage the impressionable Johanna to write things like "Oh, God -- why has this cockatoo-haired cunt been allowed out of his cage to make a second album?"

Eventually, she wises up, and Moran delivers a stellar page and a half on the poisonous effects of cynicism and its subterranean connection to fear. Even better is the whole of Chapter 24: "You rip it up and start again," goes one passage. "That is the work of your teenage years -- to build up and tear down and build up again, over and over, endlessly, like a speeded up film of cities during boom times and wars. ... You are midwife to yourself, and will give birth to yourself, over and over, in dark rooms, alone." The last paragraph is even better:

And later, over a glass of wine -- because you drink wine now, because you are grown -- you will marvel over what you did. Marvel that, at the time, you kept so many secrets. Tried to keep the secret of yourself. Tried to metamorphose in the dark. The loud, drunken, fucking, eyeliner-smeared, laughing, cutting, panicking, unbearably present secret of yourself. When really you were about as secret as the moon. And as luminous, under all those clothes.

This is marvelous, the perfect balance of adult perspective and a living empathy with the radiant confusion of youth. It's the kind of advice that every smart, compassionate person wants to convey to a kid, particularly a girl, on the cusp of adolescence, if only we could articulate it. However, it's just not fiction.

And when those opinionated, essayistic bits of the novel come, the print almost seems to glow on the page. Here is Moran firing on all cylinders, writing about life and about herself and by extension you and me. Johanna, I don't believe in for a minute except to the extent that she's Caitlin Moran, and I have next to no interest in anything that happens to her that didn't also happen to Caitlin Moran. A novelist, on the other hand, would make you forget that she even exists, so overpowering is the reality of characters.

So while "How to Build a Girl" has its charms, they're diluted ones. We can only speculate about why Moran chose to write a novel. Perhaps, because she loved novels as a girl, she wanted to provide the same experience for other young readers. Perhaps she didn't think she could write as honestly about her own family as she could about a "fictional" one. Or perhaps it's that we still live in an age where a "novel" is a prestigious thing to have written, whereas a book of advice, polemic and memoir like "How to Be a Woman," however vital and necessary and welcome it may be, is not. When it comes to judgments like that, we could all stand to do some growing up.

Shares