Is traditional masculinity — assuming for a moment that we have any idea what that term means — under attack? Some of its defenders certainly feel that way. Over the past year or two, some of the male-centric institutions in American life that have at least partly resisted the incursions of feminism have come under significant cultural pressure: the National Football League, the United States military and even the fraternity party, sacred bonding ritual of future golf-playing insurance executives and other avatars of middle-middle guy-ness. Fairly or not, those environments have become identified with a widespread social problem that is surely not limited to jocks, jarheads and frat boys: the persistence of rape, domestic violence and other crimes against women that are rarely reported and still more rarely prosecuted, and whose perpetrators are too often protected by a code of male silence and secrecy.

If the panicky, defensive identity crisis of America’s declining white majority is a principal driving force in our nation’s bitterly divided political and cultural life (as I discussed here a few weeks ago, in the wake of Ferguson), so is the rearguard defense of masculinity. When Rush Limbaugh complains that nanny-state regulations on conduct are “feminizing” football, or the national leader of an elite fraternity writes an op-ed blaming drunken young women as the real villains in a perceived campus rape epidemic (rather than, say, rapists), it’s hard to say which feels stronger — the cluelessness or the desperation. As with the Caucasian rush to define the cop who shot Michael Brown as simultaneously the hero and victim of that tragic episode, this circling of the wagons around embattled manhood seems both perverse and unnecessary.

Of course the two responses are intimately connected, not least because convincing oneself that men are a persecuted and disenfranchised group requires about the same level of mental gymnastics as explaining away the enormous social, cultural and financial advantages held by white people in American society. If anything should be obvious about this murky situation, I guess it’s obvious that it’s not about facts, but please indulge me while I air out a few. It’s true that men hold only 81 percent of the 535 seats in Congress, and roughly 94 percent of the top executive jobs in the Fortune 1000, and that represents an enormous statistical shift from the days when both those numbers were close to 100 percent. Across all races, all socioeconomic classes and all kinds of employment, men are paid more than women, by an average of more than 25 percent. That disparity has barely shifted in recent decades, but at least employment listings no longer come in two different categories, as my mother can remember from the 1950s: “Help Wanted” and “Help Wanted: Women.”

But the collective male freakout that produces nervous TV gags about “boobs on the ground” in the Middle East, or an Oklahoma Highway Patrol captain advising women not to get pulled over by cops if they don’t want to get raped by them, is not about anything as quantifiable as loss of material advantage. I agree, by the way, that both statements were blunders: The Fox News guy didn’t realize he was coming off as a pig, and the Oklahoma trooper didn’t consciously intend to blame women for the crimes of depraved cops. But that kind of public “misstatement,” by someone who ought to know better, is actually more revealing than all the overtly misogynistic trollery on the Internet. The masculinity backlash is about perception and psychology, specifically the perception that “traditional” gender roles are being undermined and that male-coded zones like the football field and the frat house are being invaded by an alien ideology.

LGBT soldiers serve openly in the military, and same-sex marriage will almost certainly go nationwide within the next few years. Transgender people are more visible and vocal than at any time in recorded history (although we have a long, long way to go on that one). A gay defensive lineman may well get into an NFL game this year — with the Dallas Cowboys, of all teams – and other pro players have come out in basketball and soccer. What comes next? In the paranoid universe of Limbaugh listeners, Obamabot drones from the Feminazi Panopticon will soon be monitoring basement poker games for inappropriate jokes, to be reported to all employers, ex-wives and local school boards for social-media humiliation and reeducation.

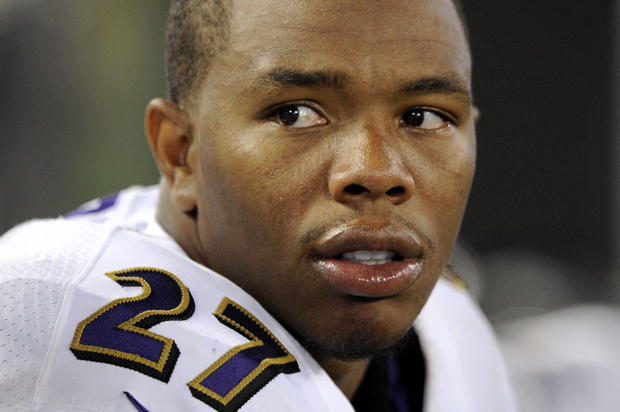

But that kind of parody is a little too easy. It’s more difficult to recognize the genuine cultural split here, and to see that for many men (and more than a few women), this is a subject of genuine pain and bewilderment. It feels as if areas of public life they were raised to venerate as unchanging symbols of American virtue and rectitude are under unfair assault. That’s how I interpret all those Baltimore Ravens fans (some of them female) showing up at the team’s first home game in Ray Rice jerseys, or all those Washington Redskins fans rallying around their team’s patently derogatory nickname. It’s an effort to draw a line in the sand, to resist the high-minded dictates of elite authority, to insist that some things are sacred and that cultural change goes this far and no further. People on the cultural left, with their DIY handicrafts and homegrown tomatoes, have a similar impulse to resist the onrushing force of a political economy built on constant revolution and reinvention, a world, as Karl Marx observed 166 years ago, in which “all fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away … all that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.”

As that may suggest, I feel an instinctive twinge of sympathy for this reaction, with its pathetic-nostalgic yearning for a mythical past of conformity and clear sexual divisions, of handsome boys and pretty girls under the Friday night lights, in an America untroubled by Vietnam or feminism or gay rights or a president with a Muslim-sounding name. I don’t say that my twinge of sympathy is entirely healthy. That imaginary world never really existed, and most people who yearn for it wouldn’t want to live there if it had. At best, it’s a blend of fantasy and collective memory, not unlike the “Morning in America” commercial that got Ronald Reagan elected, pretty much on the premise that he would restore a mythical order lost in the turbulent ’70s.

While the defense of an idealized vision of traditional masculinity is not, in itself, an apology for rape or domestic violence, it slides easily into an attempt to deflect those things, to shove them off the table, to pretend they are minor aberrations better dealt with in silence and darkness. It slides too easily into defending the indefensible, into claiming that a man punching out his fiancée is a “private matter” that is nobody else’s business, that a woman who drinks too much or wears a short skirt is to blame if she gets raped, or that a word once used to tally the killings of Native Americans is now a token of “honor” and “respect.” If anything virtuous and respectable can be redeemed from conventional American masculinity, it has to begin with listening to what other people and the world are telling us, and actually hearing it.

I too was raised by a father who could remember World War II and even the Depression, an immigrant who yearned for and could never achieve that generation’s ideal of undemonstrative, hard-drinking, neatly tailored manhood. As I recently discussed with the actor Viggo Mortensen, who plays an American man of precisely that heritage in the new movie “The Two Faces of January,” there is something praiseworthy and almost irresistible about that model of masculinity, along with much darker qualities. It might be relevant to observe that white men of the “Greatest Generation” disproportionately enjoyed an explosive prosperity that followed America’s ascension to superpower status and the growth of the labor movement. Their mode of confidence and composure rode along with steadily rising incomes and expectations, whereas their sons and grandsons — you and me, buddy — face more straitened circumstances in a vastly different world.

Can the virtues of that lost masculine ideal be redeemed without buying the whole toxic package? That question has no clear answer, and may not for years to come. Those who try to preserve its last self-parodying scraps and vestiges by rescuing the NFL from feminism and political correctness, or by blaming rape and spousal abuse on women’s autonomy — after all, if women left the driving to their fathers and husbands, they wouldn’t be at risk from pervert cops! — are fighting a contemporary version of Pickett’s Charge. It’s a misguided and self-destructive crusade on behalf of something that can’t be attained and wouldn’t be worth fighting for if it could. Very few of the Confederate soldiers who died at Gettysburg personally benefited from slavery. Yet the myth that there was something noble or sacred or romantic about their sacrifice on behalf of a brutal and toxic economic system continues to poison our national discourse, many generations later and into the indefinite future. We can only hope that the ripple effects of the battle for American masculinity don’t take quite so long to subside.