The answer to the question of whether rich people can buy elections is “Sometimes, but not always.” President Obama won reelection despite the massive amounts spent to defeat him by conservative business leaders. He beat back their spending by having a weak opponent who was seen by voters as pro-rich and out of touch. Mitt Romney lacked the personal skills to connect with voters and persuade them that he cared about the middle class.

Clearly, then, money is not the only thing that decides election campaigns. Public opinion, media coverage, campaign strategies, and policy positions matter as well. During a time of rising campaign costs and limited public engagement in the political process, money sets the agenda, affects how the campaign develops, and shapes how particular people and policy problems get defined. It takes skilled candidates, considerable media coverage, and strong organizational efforts to offset the power of great wealth.

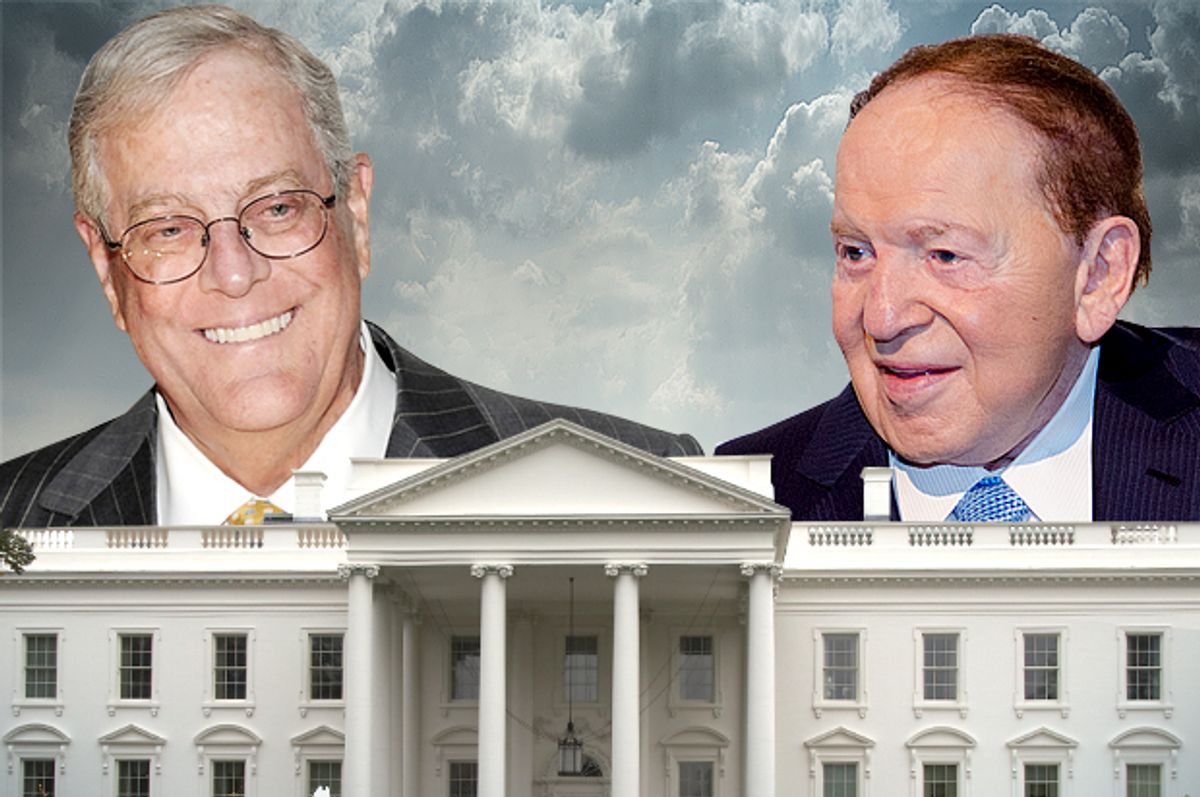

There are no guarantees that future Democratic candidates will replicate Obama’s 2012 electoral success. The conservative financiers involved then regard the money that they spent that year as the initial down payment on a long-term investment, even if it did not immediately pay off. After the general election, Sheldon Adelson announced that he planned to “double” his investment in future races. “I happen to be in a unique business where winning and losing is the basis of the entire business. So I don’t cry when I lose. There’s always a new hand coming up. I know in the long run we’re going to win.” Marc Short, one of the strategists behind the political activities of Charles and David Koch, echoed that thought: “Our members are committed to the long term, not to one individual cycle.”

In preparation for the long-term battle, these billionaires already have altered their campaign approach to maximize the odds of winning. After studying what went wrong with the 2012 campaign, individuals such as Adelson are aiming for a different kind of GOP nominee. According to Adelson’s friend Victor Chaltiel, “he doesn’t want a crazy extremist to be the nominee. He wants someone who has the chance to win the election, who is reasonable in his positions, who has convictions but is not totally crazy.” Meanwhile, Republican National Committee member Shawl Steel said that Adelson has learned from the 2012 defeat: “The candidate will have to have a strong resume—no sudden lightning-new guy—will have to build a formidable fundraising apparatus and really be emotionally tethered to bringing in middle-class Latinos, Asian Pacifics, Jews and blacks like never before.”

Understanding the importance of the top conservative billionaires, GOP strategist and former White House press secretary Ari Fleischer said that one of the most important elements in the 2016 presidential campaign would be who would win the “Sheldon Primary.” Referring to the super-wealthy benefactor, Fleischer noted that “anybody running for the Republican nomination would want to have Sheldon at his side.” The same is true for Charles and David Koch. With their abundant resources, grassroots network, and willingness to spend to influence elections, their role in the GOP is of utmost importance. And like Adelson, they have sought to learn from 2012 and develop new electoral strategies. From their perspective, it is crucial to adapt to the political environment and alter public outreach strategies. James Davis of Freedom Partners, a Koch-financed group, said donors must test and refine their message: “Being in the field and testing during the slower periods, and in smaller areas, allows you to refine strategy and tactics so that you can make the larger investments with confidence.”

For the 2014 midterm elections, Americans for Prosperity (AFP) is focusing on field operations and broadcasting ads that employ moving personal stories to deliver policy messages. Central to their approach is the idea that Obamacare is a failure and is hurting ordinary patients. “Too often, we did kind of broader statistical ads or messages, and we decided that we needed to start telling the story of how the liberals’ policies, whether it’s the administration or Congress, are practically impacting the lives of Americans every day,” explained Tim Phillips, the president of AFP. Media expert Elizabeth Wilner of Kantar Media/CMAG noted that those kinds of ads have a greater likelihood of electoral success. “Ads that tell stories are more compelling than ads that don’t,” she said. “And ads that use sympathetic figures are more compelling, generally, than those that don’t.”

With ads that have greater impact, a stronger field operation, and better candidates, conservative billionaires are likely to have greater success in the future. Worried about that possibility, Democrats have countered with a “running against the billionaires” strategy. This is a tactic that was used successfully by Barack Obama in his re-election bid. He tied his GOP opponent Mitt Romney to billionaires such as Sheldon Adelson and the Koch brothers, who were spending hundreds of millions against him. Obama appealed to basic fairness and argued that a candidate backed by the mega rich would not fight for the middle class and help ordinary people.

Senate majority leader Harry Reid (D-Nevada) has copied this approach for the 2014 elections. In a series of speeches on the Senate floor, he bemoaned the unfairness of tycoons and the millions that they are spending to defeat vulnerable Democrats in key swing states. Reid decried the radical agenda “that benefits billionaires at the expense of the middle class.” Continuing, he said that “the oil baron Koch brothers are very good at protecting and growing their prodigious future and fortune. There’s nothing un-American about that. But what is un-American is when shadowy billionaires pour unlimited money into our democracy to rig the system to benefit themselves and the wealthiest one percent.”

Democratic senators under attack by Americans for Prosperity ads costing millions of dollars responded with their own ads directly targeting the Koch brothers. One spot broadcast by Alaska

Democratic senator Mark Begich complained about a local oil refinery shut down by Koch Industries: “They come into town, buy our refinery, and just run it into the ground, leaving a mess. A lot of Alaskans are losing jobs, and I’m definitely concerned about the drinking water. I don’t go down and tell them what to do; I expect them not to come up to Alaska and tell us what to do.”

Upset with these personal attacks, Charles Koch penned an article in the Wall Street Journal entitled “I’m Fighting to Restore a Free Society,” in which he decried “collectivists [who] engage character assassination.” He said that his companies employ 60,000 Americans and that his workers have won “over 700 awards for environmental, health, and safety excellence.” Continuing his self-defense, he said that “far from trying to rig the system, I have spent decades opposing cronyism and all political favors, including mandates, subsidies, and protective tariffs—even when we benefit from them. I believe that cronyism is nothing more than welfare for the rich and powerful and should be abolished.”

Irritated that Reid was focusing on the Kochs, Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) said that he “wondered why he left out billionaire Tom Steyer, who plans to spend as much as $100 million pushing the issue of climate change in the 2014 election and appears positioned to rival the deep-pocketed Koch brothers.”

Democrats face interesting strategic decisions with respect to billionaires. For more populist-leaning candidates, the preferred approach is to attack billionaires, complain about unfairness, and criticize the lack of transparency in their electioneering activities. Other Democrats, though, have chosen a different tack. They have embraced liberal billionaires rather than running against billionaires as a general class. Their thinking is that “if you can’t beat them, you should join them.”

An example of that alternative comes from Democrats loosely aligned with Hillary Clinton. Thinking ahead to a possible presidential campaign in 2016, her super PAC, Ready for Hillary, has signed up George Soros as co-chair of its national finance council. In contrast to his aloofness from Obama in 2012, Soros agreed to assist the group laying the groundwork for her campaign three full years before the election. Michael Vachon, the political director for\ the billionaire, explained Soros’s early action by saying that “his support for Ready for Hillary is an extension of his long-held belief in the power of grass-roots organizing.” The Clinton super PAC also has received contributions from billionaire Alice Walton, one of the heirs to the Wal-Mart fortune, and Marc Benioff, the billionaire CEO of Salesforce, along with a number of other wealthy individuals. Mrs. Clinton’s family foundation is working with billionaire Tom Steyer on an early childhood development project.

Clinton’s accommodationist approach clearly reflects the pragmatic conclusion that Democrats need abundant resources to fight the conservative billionaires aligned with the Republican Party. In light of recent Supreme Court decisions opening up the big money spigot, Democrats appear to believe that they must join the arms race that now characterizes U.S. campaign finance. However, that approach comes with some pitfalls. In cozying up to billionaires, Clinton and her supporters risk alienating the populist wing of her own party and turning off voters still stewing over the Wall Street interests that they think brought down the American economy during the financial collapse. If she goes too far with this strategy, she risks facing a progressive backlash during the nominating process.

The unresolved political question is how this party division over billionaires plays out. Dividing billionaires into warring factions may be the best hope for Democrats. But that choice means that Democrats should downplay the populist rhetoric and embrace pro-growth policies. They would have to quit talking about raising taxes on the rich and endorse actions that broaden social and economic opportunity.

Even if Democrats run against conservative billionaires, they are likely to embrace moderate and liberal ones in both 2014 and 2016. The 2016 election will be a multibillion dollar battle for the future of America, and Democrats cannot compete without having ultrarich supporters willing to spend tens of millions on their behalf. It matters considerably to democracy as a whole how Democrats resolve this strategic and policy issue. The outcome of future elections depends in good part on whether 2016 becomes the year of conservative billionaires, liberal ones, libertarian tycoons, or a diverse set of billionaires across the political spectrum.

Excerpted from "Billionaires: Reflections on the Upper Crust" by Darrell M. West (Brookings Institution Press, September 2014). Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares