In 1975, facing the prospect of municipal bankruptcy, New York City Mayor Abe Beame moved to lay off nearly 11,000 police officers, firemen and other uniformed personnel — and sparked one of the more bizarre controversies of the city’s history.

The Council for Public Safety, representing 27 labor unions, responded by printing nearly a million copies of a pamphlet called “Welcome to Fear City: A Survival Guide for Visitors to the City of New York.” Beneath a death’s-head cover, the text urged tourists to avoid the streets after 6 p.m., remain in Manhattan, and, emphatically, “never ride the subway for any reason whatsoever.”

Beame called the idea “a gross outrage”; and, in the end, the unions opted for the more moderate hand-out, “If You Haven’t Been Mugged Yet.” The macabre leaflets never saw the street.

The stunt itself may not be especially remarkable. (Just last year, for example, following a spate of deaths on the subway, the city’s Transit Workers Union 100 planned to hand out blood-spattered Metrocards to straphangers.) But if the tactics were textbook, the reaction from the mayor’s office was an expression of real concern, implying that the grim advice might be taken seriously.

How did America become afraid of New York? Sure, the city was dangerous, relative to its recent history — but it wasn’t more dangerous than other American cities of the era. The credit, at least in part, lay with Hollywood. On-location filming in the city tripled during the Lindsay administration, between 1966 and 1974. Doomed Gotham became not just the setting of the era’s great films, but their subject. “As reflected in good movies and bad, serious ones as well as forthrightly foolish,” the critic Vincent Canby wrote in 1976, “New York City has become a metaphor for what looks like the last days of American civilization.”

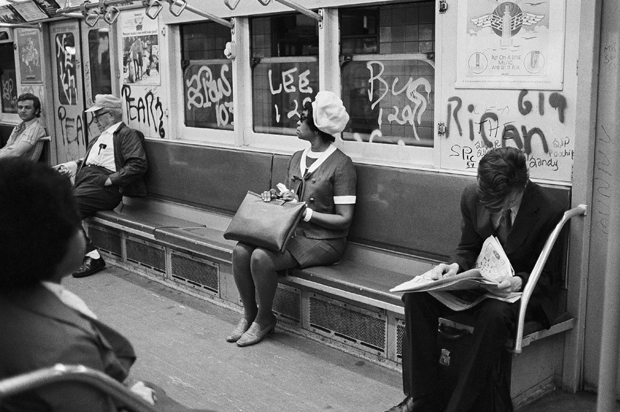

Within the extended metaphor, there was no more potent symbol of danger than the New York City subway.

The year of “Fear City,” for example, saw the release of two Hollywood films about murder and mayhem on the subway, “Death Wish”and “The Taking of Pelham 123.” Three years earlier, “The French Connection,” a drug trafficking thriller with a famous subway chase, became the first R-rated movie to win the Best Picture Oscar. Its poster showed a murder on the familiar covered stairs of a Brooklyn elevated station. Four years later, in “The Warriors,” director Walter Hill transformed the city’s proud transportation system into a deserted and fantastic gangland.

These movies prompted public conversations about reality and cinema. After “Death Wish,” a gruesome vigilante flick in which Charles Bronson’s character murders four muggers on the subway (and six above ground), smashed the house record set by “The Godfather” at an Upper East Side movie theater, the cultural critic John Corry confessed he felt “a tension on the subways now that there never was before.”

When “Pelham” was released, New York Times reviewer Nora Sayre wrote that it had captured the city’s “crisis mentality.” “The hijacking seems like a perfectly probable event for this town,” she wrote. “Perhaps the only element of fantasy is the implication that city’s departments could function so smoothly together.”

Revisit the ’70s subway films, as I have at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s “Retro Metro” series, and these cinematic developments start to seem inevitable — inherent to the subway, rather than a product of the time. Straphangers are helpless, confined and exposed to the madness and violence of their companions. For the lawless, the underground is a playground and a ready-made escape route. The spatial peculiarities of the subway seem designed to host the dark dramas of the age.

Add to that the system’s lack of spatial or temporal context — midnight at a station in Queens looks exactly like morning in Manhattan — and you can see how any subway image seems to have come right from your local station. The subway is every New Yorker’s “second neighborhood.”

In fact, these frightening cinematic tropes were a contemporary innovation. Before “The Incident” and Amari Baraka’s “Dutchman” (two sinister and violent subway films released in 1967), the subway had quite a different reputation. Perhaps there was a “nut in every car,” as Bill Cosby remarked, but not a murderous nut. The general effect was harmless and even amusing. “All the entertainment you want for 15 cents,” he joked in 1963, “I saw a three-act show from West 4th St. to 125th St.”

Look back to the films shot on the subway in previous decades — like “The Crowd,” “Applause,” “Speedy” or “On the Town” (the latter two also showing at BAM this week) — and you see how the same features of the subway setting were manipulated to different ends. The presence of other New Yorkers, far from being frightening, brought comic potential. Being stuck in a car or left behind on a platform opened the door for coincidence or romance. Underground mobility wasn’t a criminal asset, it was a source of adventure.

Granted, New York had changed a lot by 1975, the year Beame dictated that conductors should lock the doors in the rear of late-night trains, crowding passengers together in the front. And yet, representation had gone well beyond reality. A typical day in 1979, the year “The Warriors” came out, saw 20 felony complaints logged in the subway system — a shocking number by today’s standards, but fewer than in most city police precincts. The crime rate on the subway (per 100,000 riders) was 18 times lower than in the city at large (per 100,000 residents). You were safer underground than above.

Those statistics didn’t snuff out the fear. When Bernie Goetz shot four teenagers on a Brooklyn-bound 2 train in 1984, in a situation that bore some similarity to a scene in “Death Wish,” national media had a field day. Time reported the “dread” that New Yorkers felt “descending into the underworld.” The image of the New York City subway, reported the New York Times, was of a “lurid underground kingdom ruled by murderers, rapists and muggers where a subway rider’s life sometimes has less value than a token.”

That the murderous slant of subway cinema might be a public relations issue was not beyond the notice of the Metropolitan Transit Authority. Back in 1967, “Dutchman” director Anthony Harvey had been forced to shoot on replica cars due to the film’s violent content. “The French Connection,” “The Warriors,” and “Pelham” all received permission to use the subway. Hijackings, murders and roller-skate bathroom melees were fine — but the MTA insisted the directors shoot with graffiti-free trains.

Rehab wasn’t easy, even as Ed Koch and Rudy Giuliani wiped the subway of its famously colorful coat. In 1994, the MTA decided it would no longer indulge the imaginations of Hollywood filmmakers. “We don’t look fondly on projects that depict the system as being out of control,” a spokesman said. “We don’t want bullets whizzing around subway cars. We don’t want bloody bodies strewn all over the subway cars.”

“There’s a perception out there,” Governor Mario Cuomo remarked in 1992, “that New York State is New York City and New York City is Manhattan and Manhattan is a subway that murders people every night.”

New Yorkers hadn’t necessarily thought of it that way. When Leslie Harris shot “Just Another Girl on the IRT” that year, she saw the system as representative of the city’s energy. The title was meant to illustrate the gap between straphangers’ perception and reality; the wrongness of the easy judgments invited by travelers’ extended proximity.

These days, even the bad moments aren’t so bad anymore. When Lena Dunham’s character in “Girls” falls asleep on a Coney Island-bound train, her purse is removed so gently she doesn’t even wake up.