After a week spent shifting his position on climate change, Rep. Cory Gardner, the Republican challenging Mark Udall of Colorado for his Senate seat, finally met his match: the yes-or-no question.

In a debate Tuesday night, the Colorado candidate was asked to give a simple, one-word answer to the question of whether "humans are contributing significantly to climate change."

He couldn't do it. Even though, as the debate's monitor explained to him, he'd later get a full minute to explain his answer. Even though the scientific community overwhelmingly agrees that human activity is the main cause of climate change.

"Look, this is an important issue and I don't think you can say yes or no," Gardner plead. He got the first part right.

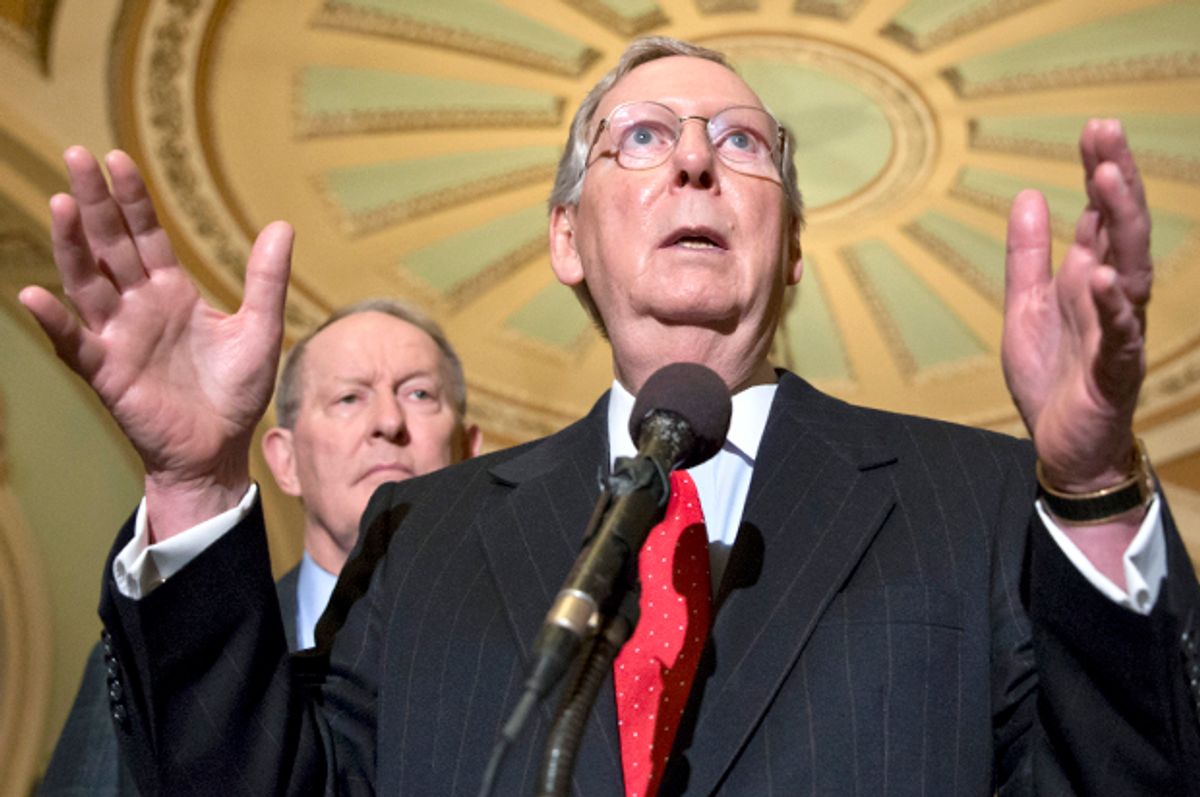

Also this week, over in Kentucky, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell spent an excruciating 14 minutes on a sports radio program, which only got more awkward when host Matt Jones asked him whether or not he believes in global warming.

“What I have said repeatedly is I’m not a scientist," he replied, getting off to an inauspicious start. "But what I can tell you is, even if you thought that was important -- and there are some scientists who do and some scientists who don’t -- but even if you thought that was important, the United States doing this by itself is going to have zero impact."

"Senator, that's a 'yes or no' question," Jones pushed. "Do you believe in global warming?"

"No it isn't. It is not a yes or no question," McConnell snapped. "There are differences of opinion among scientists. My job is to try to protect jobs in Kentucky now, not speculate about science in the future."

In New Hampshire, meanwhile, Senate candidate Scott Brown had some difficulty defining his own stance on climate: Is climate change "absolutely" real and caused by a combination of man-made and natural factors, as he claimed in 2012, not scientifically proven, as he asserted in late August,or, wait, actually, the first one: Monday night, Brown was back to the "real and caused by a combination of factors" stance, which his campaign confirms is his actual position.

Following that?

These pols may not be scientists, but they're not stupid. Gardner himself acknowledged, just a day before the debate, that "there is no doubt that pollution contributes to the climate changing around us." And McConnell ... well, he still denies, against all evidence to the contrary, that the climate is even changing. But if anything, we should probably just call him stubborn.

Privately, Bloomberg recently reported, many Republicans in office do believe that humans are causing climate change -- as do 52 percent of their constituency -- and that something needs to be done. But what these self-contradicting Republicans, so keen to boast of their lack of scientific education, seem to be realizing that when it comes to climate change, there's no safe place to stand.

Things weren't always so complicated. Legend has it, prominent Republicans once readily believed that man-made climate change was happening and, having accepted the science, took the natural next step of supporting climate action. "We stand warned by serious and credible scientists across the world that time is short and the dangers are great," John McCain said during his 2008 presidential campaign. And so, "we need to think straight about the dangers ahead and to meet the problem with all the resources of human ingenuity at our disposal."

Obviously, things have changed. By March of this year, McCain had dialed things way back, telling Time that, while he's still interested in climate change, "I just leave the issue alone because I don’t see a way through it." So much for the power of human ingenuity.

According to Bloomberg, McCain's current position is the one most Republicans have found themselves caught in: believing that not much is going to happen, legislatively, to make a significant difference in greenhouse gas emissions. So they're better off, the thinking goes, keeping the Tea Party happy by bowing out of the debate entirely -- by trying to change the subject, by using their lack of scientific degree to disqualify them from stating an opinion and by hedging, avoiding, at all costs, that yes-or-no question.

But here's the problem for these politicians: 400,000 people marching in the streets of New York say leaders can no longer ignore the issue and hope it goes away. What we're seeing now is politicians confronted with the awkwardness of finding a position on climate that's both politically tenable and yet not entirely mockable. They're damned if they do, damned if they don't: Answer the question with a no, and they'll be slapped with the cold, hard facts, their anti-science stance putting them at risk of alienating moderate and younger voters. But acknowledge that there is a problem, and they're basically making the de-facto admission that something has to be done to solve it.

That's what Gardner was trying to get around in his wordy answer to a simple question. The congressman understands that a "yes" implies a need for action, and as such had to qualify his response with the assertion that climate change, while happening, isn't the big deal the media makes it out to be. It's why McConnell, in the same breath in which he was disavowing the reality of climate change, also argued that any steps the U.S. took to reduce emissions wouldn't have a significant impact.

But those qualifiers, too, fall apart under scrutiny. The "highly conservative" U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found, in its most recent report, that we're already feeling the effects of climate change, and that, barring significant action to reduce emissions, they're only going to get worse. Even in the best-case scenario, the one seized upon by Gardner in Brown, in which humans turn out to have the least possible effect on the climate, we'll still only be able to avoid the most dangerous effects of warming if our extremely good luck is coupled with aggressive steps taken to reduce emissions. A failure to take action on the part of the U.S., regardless of how effective that action turns out to be, is tantamount to throwing in the towel, and allowing us all to continue on a course we might not be able to recover from.

And a defeatist attitude like that does not make for a very electable candidate.

So what's a Republican hoping to stake out a viable position on climate change to do? None of the candidates seem to have figured that out, hence all the stammering, bumbling and self-contradiction every time the issue is raised. Perhaps the answer is simply that there isn't an answer; at least, not one that's both based in reality and tenable for the party as it currently operates. But seeing as how the science is only getting stronger, and the impacts of climate change more and more apparent, the GOP had best get busy working on an answer they can live with. Because the question isn't going away.

Shares