It's been a couple of weeks since the National Review published Kevin D. Williamson's cover story examining everything he does not like about Lena Dunham. Whether or not it was intended as the act of quarantine I interpreted it as, the full piece was locked behind a paywall, effectively separating the people who think Williamson is a credible writer from the rest of the population. The part that was available online dealt exclusively with a chapter in Dunham's book in which she wrote about being sexually assaulted, and Williamson's response was just as vile as you'd expect.

But last week, a right-wing site called Truth Revolt picked up an excerpt of Williamson's piece that hadn't gotten much traction because it was behind the paywall. Then the rest of the Internet picked up the story. Which is where we are now.

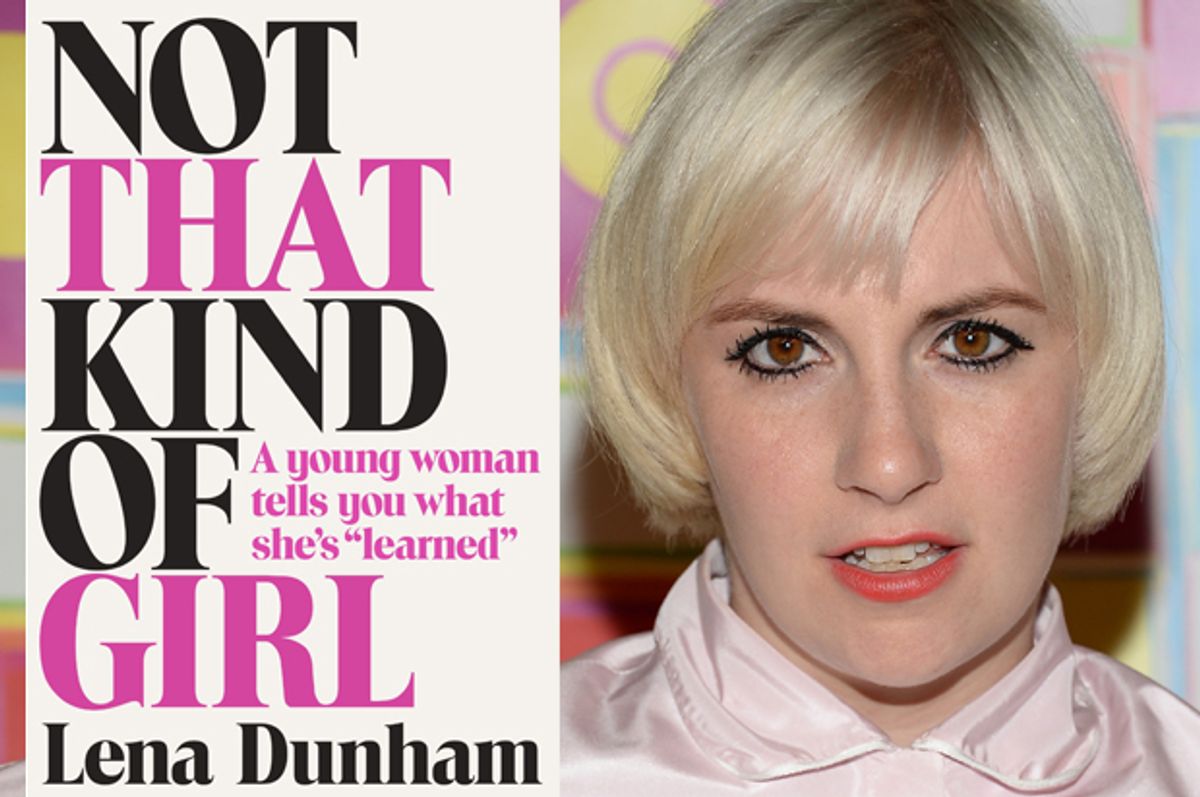

In brief, Williamson used an anecdote in the book in which Dunham, at age 7, looks inside her 1-year-old sister's vagina to add to his case about why he hates her so much. Truth Revolt picked it up and ran with it in a piece titled, "Lena Dunham Describes Sexually Abusing Her Little Sister." Dunham responded by calling the accusation "really fucking upsetting and disgusting."

It's easy to dismiss Williamson and Truth Revolt for being misogynistic, racist and transphobic trashheaps, but the story has also taken on new life among feminists, some who have asked that Dunham be removed as a spokesperson for Planned Parenthood. It seems that Williamson's grossness has incited a conversation, at turns earnest, cynical, messy and terribly ugly, about Dunham's privilege, child-on-child sexual abuse and what constitutes "normal" exploration among children.

A few things here. As much as I do not like reading thinkpieces about feminism and Twitter, I like writing them even less. So I am not going to do that. After reading the book, I did not leave with the impression that Dunham was a predator who was grooming her sister for sexual abuse. I left with the impression that she was a curious, sometimes dark kid with self-identified boundary issues that, as was made clear in the book, she has been working her entire life to address through therapy and in dialogue with members of her own family. Some people feel differently about what was represented in the book based on their own experiences, and that's their right.

People can feel lots of different things about Lena Dunham and her body of work. What I'm not comfortable with, and certainly not under the mantle of supporting victims and building a culture of consent, is for people to create a narrative of victimization and abuse for Grace Dunham that she has never claimed for herself. Doing that gets into some really nasty territory that I find to be profoundly anti-feminist and also undermining of the entire project of letting women be the authors of their own lives.

Which is part of what felt so uncomfortable about the conversation unfolding over the weekend -- just how comfortable some people seemed when speaking on Grace Dunham's behalf. That changed on Monday when she chose to speak out. Addressing both the conversation about what constitutes "normal" behavior for a second grader and the quickness with which people claimed the victim label without her consent, Grace tweeted:

heteronormativity deems certain behaviours harmful, and others "normal"; the state and media are always invested in maintaining that

And then:

As a queer person: i'm committed to people narrating their own experiences, determining for themselves what has and has not been harmful

To push back against a narrative that says Lena Dunham is a remorseless predator is not to say that children cannot sexually abuse other children. It is not to say that white privilege does not protect abusers. It is not to say that the women who have been sharing their own experiences of pain and victimization are wrong to have felt triggered by the excerpts from the book being circulated. It is not to say that Lena Dunham or her body of work is above critique.

But I'm more interested here, in this specific expression of a larger conversation about abuse and accountability, in listening to and respecting the experience of the person this story is really about. And it's not about Lena Dunham or Kevin D. Williamson or anyone else. This is a story about Grace Dunham.

Shares