There comes a moment in Bennett Miller’s film “Foxcatcher” when we see beneath the surface of John Eleuthère du Pont, the hawk-nosed, liver-spotted zillionaire played by Steve Carell, and begin to appreciate just how deeply crazy he is. Heir to one of America’s greatest family fortunes, du Pont has begun to build an elite amateur wrestling team at his rural Pennsylvania estate in the mid-1980s, with Olympic gold medalist Mark Schultz (Channing Tatum) as its centerpiece. Although the relationship between the isolated rich man and the young athlete from a hardscrabble, semi-orphaned background is always tense, things seem to be going well, and du Pont tells Mark he doesn’t want to be addressed as Mr. du Pont anymore. “I consider us friends,” he tells Mark in genial tones, “and most of my good friends call me Eagle. Or Golden Eagle. Or Coach. Or John.”

Even beyond the hilarious narcissism and total lack of self-awareness, the problem here is that John du Pont has no friends. So no one has ever called him “Golden Eagle,” unless they have been paid to do so. He has people who work for him, people he can buy and throw away at need, just as he buys military hardware and helicopters and training facilities and entire wrestling tournaments. At least according to the account in “Foxcatcher” – which was written by E. Max Frye and Dan Futterman, and largely based on Mark Schultz’s memoir – du Pont created tournaments for wrestlers over 50, and then had his opponents paid off to lose to him. (He himself had not wrestled since high school, and wasn’t especially good even then.) But when it comes to personal relationships, he evidently has none. No wife, no girlfriend or boyfriend, no overt sexuality of any kind and no friends. At one point, du Pont tells Mark that when he was 16 he figured out that his mother was paying her chauffeur’s son to be his “best friend.”

“Foxcatcher” is based on the bizarre true-crime story of what happened between du Pont, Mark Schultz and Mark’s charismatic older brother Dave (Mark Ruffalo), who was also a 1984 Olympic gold medalist and later became the “assistant coach” of du Pont’s Team Foxcatcher. (Du Pont was always the head coach, despite his total lack of qualifications.) You can easily Google the details, but many viewers won’t remember the case or won’t want to know. More to the point, “Foxcatcher” is another strange and compelling anthropological drama from Miller, a director with evident expertise at enabling Oscar-worthy star performances. Miller’s three features now assemble themselves into a pattern: a one-word title (“Moneyball,” “Capote”); a tremendous cast, anchored by a big-name actor as an eccentric and/or genius (Philip Seymour Hoffman as Truman Capote, Brad Pitt as Billy Beane and now Carell); and a story about the ambiguous power relationships between American men.

I’d rather not go down the bottomless rabbit hole of Oscar speculation in early November, but let’s acknowledge that it’s there. With at least four of the major best-picture contenders now in the marketplace (this movie, “Birdman,” “The Theory of Everything” and “Interstellar”) and several others beginning to generate word-of-mouth (“The Imitation Game,” “Inherent Vice,” “Into the Woods” and Angelina Jolie’s “Unbroken”), there’s nothing close to a consensus front-runner. That unusual situation may benefit “Foxcatcher,” which will strike some viewers as a cold and clinical exercise but is made with tremendous craft and intelligence and offers the chance to see at least three major Hollywood stars in a new light. Those are all things academy voters love; even without obvious sentimentality or epic sweep, this movie will be a lot of people’s second choice.

“Foxcatcher” is a gripping yarn all the way through, even if we’re not entirely sure what the point is. Carell is so convincing, so unrecognizable and so profoundly chilling as John du Pont that you quickly move through the reaction of “Whoa! That’s Steve Carell with a fake nose!” and out the other side. There’s an element of high-wire walk to Miller’s cinema, a combination of craft and daring that defines its own purpose: He’s going to engage you with a story set in a world you may not know about or care about (in this case, the intersection of amateur sports and big money), and he’s going to give big stars the chance to disappear into a meaty dramatic performance. There can be no doubt about Carell on that front, and, honestly, he could have skipped the fake honker (most outrageous schnozz seen in Hollywood since Nicole Kidman’s in “The Hours”). His blocky, slightly hunched body language, his stolid and obtuse gaze, the expression conveying a certainty that the world will never live up to his exalted expectations – everything about du Pont suggests a guy who can have everything his own way but is never satisfied with it.

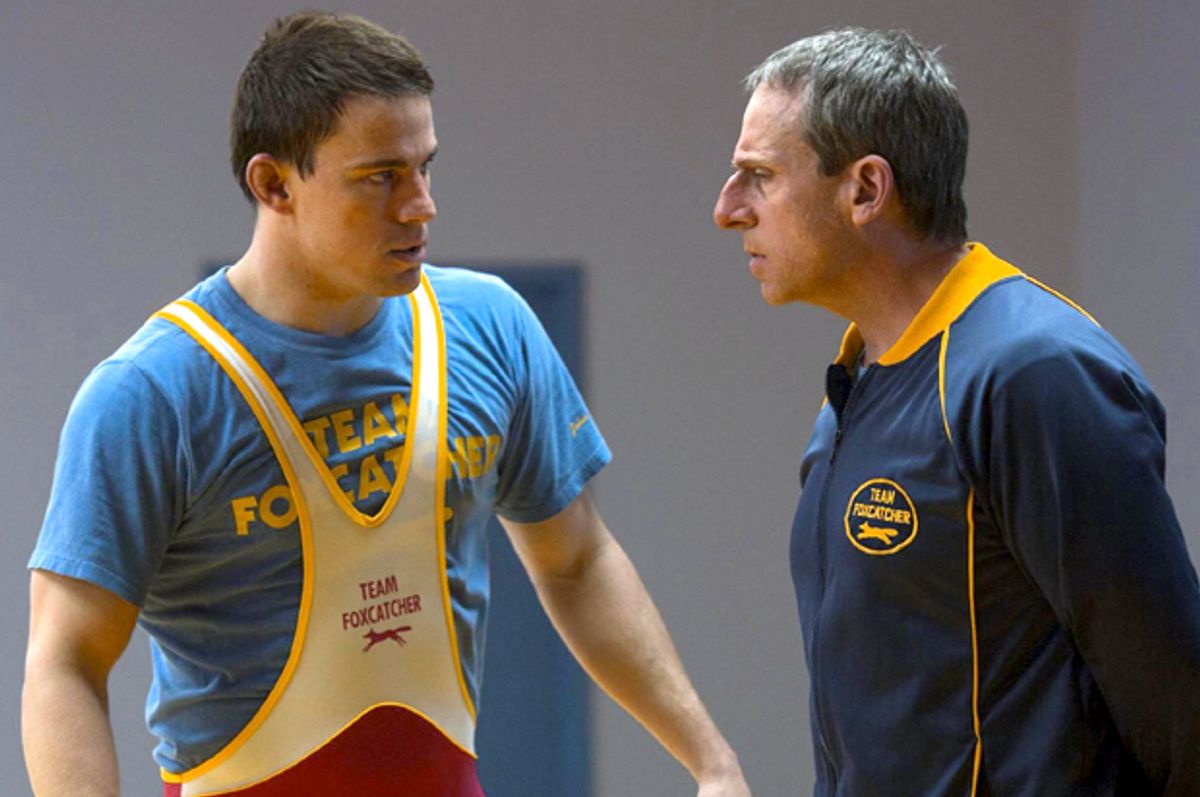

If Carell’s performance is the undoubted centerpiece of “Foxcatcher,” and he’s the probable Oscar nominee in the cast, Channing Tatum’s performance as the nearly monosyllabic Mark Schultz is arguably even more delicate. Tatum excels at playing men who are at home in their bodies but at sea in the social world, and we can feel Mark’s yearning to find a father figure in “the Golden Eagle of American sport,” and his momentary belief that du Pont’s canned Reagan-era patriotism expresses passions he himself cannot articulate. And then there’s Ruffalo, who may give the most startling performance of the three, completely abandoning his loosey-goosey L.A. bohemian look to play Dave Schultz as a deeply competitive but well-adjusted family man, the kind of guy middle American dads want for a son-in-law.

When du Pont first summons Mark to the Gilded Age excess of Foxcatcher Farms, with its neoclassical manse set among rolling acres of southeastern Pennsylvania’s horse country, Mark is scraping out a living as an assistant wrestling coach at a small college, and taking $20 speaking gigs at middle schools. Du Pont’s pitch is resonant and straightforward: The Soviet Union supports its amateur athletes with first-rate training facilities, living quarters and steady sinecures; the United States doesn’t. Fortunately for American sports, the Eagle has landed. This isn’t in the movie, but du Pont’s athletic interests went well beyond wrestling: He also sponsored teams in swimming, track and the modern pentathlon.

Indeed, one could argue that the real John du Pont had a complexity we don’t see in “Foxcatcher.” While his interest in ornithology is mentioned, the movie makes it sound like a hobby. In fact, du Pont had a Ph.D. and was an academic expert on the birds of the Philippines and the South Pacific, who helped identify several new species. Maybe that omission doesn’t much matter; like all “based on a true story” films, “Foxcatcher” streamlines its chronology and compresses and condenses the facts to fit the needs of narrative. But it does provide a hint that Miller and the writers are cheating just slightly in the direction of freak show, and also toward a fable of original sin.

In part, the filmmakers are trying to answer the question that always hovers over “Foxcatcher”: This is a weird and troubling story, all right -- but what’s it really about, and why tell it now? Maybe that question doesn’t require an answer, and I’m sure Miller would say he wants the viewers to answer that for themselves. (Because that’s the only thing a director would ever say.) But there are some hints of moral parable in the emphasis on the sources of the du Pont millions, and on the way du Pont ultimately lures the ascetic Mark Schultz into a life of booze, cocaine and dyed blond hair. There’s no such thing as clean money when you’ve got that much of it, but the du Pont fortune was literally built on death and poison (that is, on war munitions and chemical manufacturing). Was the psychotic saga of the rise and fall of Team Foxcatcher just another crazy American story, or the end-stage expression of some really bad karma?

Shares