Congress is rich. The average net worth in Congress is a bit more than $6 million, while the median net worth is $1 million. To put that in context, $4 million in net worth is enough to put someone in the top 1 percent, and $660,000 is enough to put an individual in the top 10 percent. Meanwhile, the median family wealth for whites is $134,000 and for blacks is $11,000. Emerging political science research suggests that the implications of this class bias are profound and important.

Political scientists have long debated the importance of “descriptive representation” or “reflective democracy.” Reflective democracy means that representatives share salient characteristics with their constituents. Most political scientists now agree that reflective representation leads to better substantive representation: that the interests of constituents are being reflected by legislator choice.

It’s increasingly clear that descriptive representation matters, particularly as related to race and gender. Political Scientists Robert R. Preuhs and Eric Gonzalez Juenke find that black and Hispanic legislators are more responsive to the interests of black and Hispanic constituents than white legislators, after controlling for party. Legislators of color also serve an important veto function — preventing laws from passing that would disproportionately harm communities of color. Daniel Butler and David Broockman find that politicians are more responsive to letters from constituents of the same race. This is confirmed by a study that finds legislators that support voter ID laws are less likely to respond to inquiries from Latino constituents. Further, black legislators are also more likely to hire black staffers. In addition, Economist Ebonya Washington finds that having a daughter makes a congressperson more liberal, particularly on reproductive rights. Some studies suggest that female representatives are more likely to set an agenda around women’s issues.

Given this, should we worry that more than half of all members of the House of Representatives are millionaires? Further, while two-thirds of the population don’t have a college degree, only two House members (Robert Brady of Pennsylvania and Stephen Fincher of Tennessee) and one senator (outgoing Mark Begich of Alaska) lack one.

Nicholas Carnes of Duke University has recently taken up the question of how class affects votes. In a 2012 paper, he finds that “representative from working-class occupations exhibit more liberal economic preferences than other legislators, especially those from profit-oriented professions.” Other research has confirmed this. Christopher Witko and Sally Friedman find that “House members with business backgrounds have closer relationships with business interests… and demonstrate more probusiness roll call voting.”

While descriptive representation of women and people of color has increased dramatically, the descriptive representation of working-class people has remained stubbornly flat (see chart).

As Carnes writes,

If millionaires were a political party, that party would make up roughly 3 percent of American families, but it would have a super-majority in the Senate, a majority in the House, a majority on the Supreme Court and a man in the White House. If working-class Americans were a political party, that party would have made up more than half the country since the start of the 20th century. But legislators from that party (those who last worked in blue-collar jobs before entering politics) would never have held more than 2 percent of the seats in Congress.

Those data end in 1998, but Carnes maintains his own database using similar metrics that picks up again in the mid-2000s. He finds that the line has remained flat, or if anything declined. At the state and local level, the picture isn’t much better. According to the National Council of State Legislators, the share of legislators who worked in business in a non-managerial position (i.e., workers) has declined from 4.4 percent in 1976 to 2.8 percent in 2007.

Carnes defines class by occupation, and although his main regression finds that high-income congresspeople are more economically conservative than other members, the results are not statistically significant and not as strong as the correlation with occupation. However, other studies suggest that certain votes certainly contain an income component. Michael Kraus and Bennett Callaghan find that rich members of the House are more likely to accept high levels of inequality than less rich members. The effect is particularly strong on Democrats (see chart).

In a recent study, political scientist Christian Grose finds that “members of Congress with more money invested in the stock market were more likely to vote to increase the debt limit, presumably in order to avoid a market crash.” John Griffin finds that wealthier legislators were more likely to cosponsor and vote for bills to repeal the estate tax. This held even after controlling for party affiliation, their views on other taxes and their constituent opinions. A Mother Jones investigation finds that the 10 richest members of Congress (a bipartisan group) all voted to extend the Bush tax cuts.

It is therefore clear that we need more workers in office, but what will the impact be for the gains of women and people of color? Carnes finds that we can have our cake and eat it too. Using the Local Elections in America Project (LEAP) database of 18,000 local and county elections in California, he finds that working-class candidates are less likely to be white men that white-collar candidates (see chart).

At the federal level, Carnes finds that between 1999 and 2008,

the average male member of Congress spent about 1 percent of his labor precongressional career in working-class jobs, while the average female member spent about 3. The average white member spent an average of 1 percent of his career in working-class jobs, compared to 3 percent among the average black or Hispanic member and 5 percent among the average Asian member.

It is clear, then, that policies to increase working-class representation in Congress might also increase the representation of women and people of color. But what policies could do so? Carnes tells Salon that in yet unreleased research he finds that publicly financing elections can increase working-class representation.

This isn’t surprising. A study of New York City’s public financing scheme finds that it increased the class and racial diversity of political donors. Carnes also argues that recruiters need to do more to encourage working-class voters to run. In a recent paper with David Broockman, Melody Crowder-Meyer and Christopher Skovron, he finds that “party leaders exhibit some biases against blue-collar workers” which likely prevent many from running. Research on the lack of candidates of color has also found such biases.

Carnes tells Salon that another solution is programs like the AFL-CIO “Labor Candidate School,” which began in New Jersey but now exists in North Carolina, Oregon, Nevada, Maine, New Haven and New York City. The programs, which train politically savvy members to run for office, have a good success rate; 75 percent of those who run after going through the New Jersey program win their races. Carnes tells Salon he’ll be working on an effort in Durham next year. “I believe in the potential of this model so much, I’m going to try it out myself,” he says.

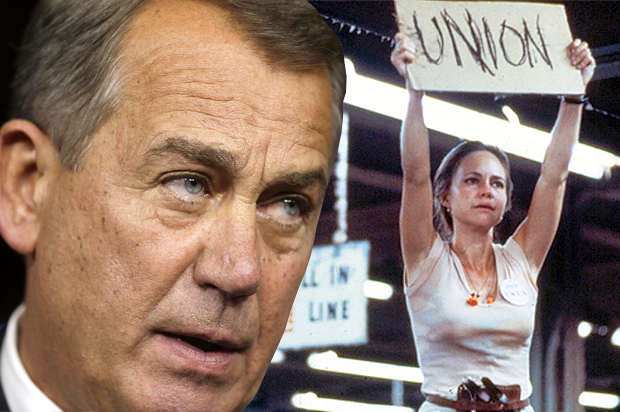

As the Democratic Party increasingly moves to the center to please an elite donor base, the last hope for action on economic inequality might be more blue-collar politicians.