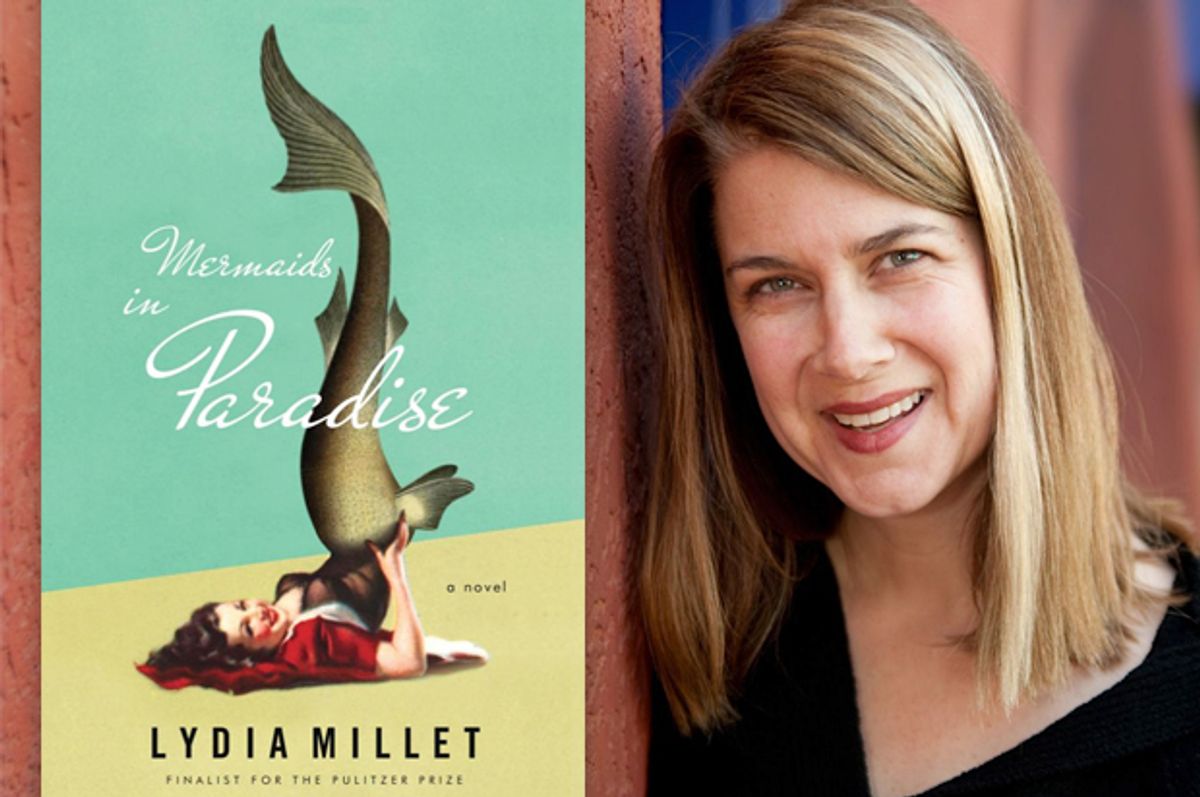

I never expected anyone to write an environmental thriller about mermaids in the comic vein of a modern-day P.G. Wodehouse because, really -- who would? Certainly I wouldn't have picked Lydia Millet, author of a trio of linked short novels about humanity's relationship to the animal kingdom, to have written it. "How the Dead Dream," "Ghost Lights" and "Magnificence" are beautiful, haunted, enigmatic works, leavened with dashes of humor, yes, but nothing likely to make you embarrass yourself, as I did, by laughing out loud in a cafe.

Yet perhaps I shouldn't have been surprised to find Millet's new novel, "Mermaids in Paradise," so funny. I first stumbled across her work in a collection of essays on "Star Wars." Millet's entry, "Becoming Darth Vader," was both a sly exploration of the tragic, erotic allure of a comic-book-style villain and an amusing survey of the various ways Millet has attempted to project her personality into the world, beginning with her girlhood Halloween costume as a "fairy-princess-queen": "Should some insufficiently humble unbeliever say, glancing at the delicate silver-and-gold crown my father had fashioned for me out of a mesh of pipe cleaners and bulbous Christmas ornaments, What are you? A princess? implying, I knew even then, a rank pretender to the throne? I could wave my scepter and scoff: Not just a princess. Also a queen. For obvious reasons, I could not be only a queen; queens were old, and often ugly."

But Millet's three environmental novels have been mostly serious and melancholy, whereas "Mermaids in Paradise" is a romp, albeit a romp with sharp teeth. It's narrated by Deb, a young Southern California businesswoman engaged to a golden retriever of a guy named Chip. The first couple of chapters describe their betrothal and wedding, complete with a bachelorette party at "some kind of Goth, medieval-bloody S&M fetish club" organized by Deb's pathologically ironic best friend Gina. (Gina, despite being tenured, describes herself as a "failed academic," a term she herself deems "redundant.")

Deb herself is on the detached side. She genuinely loves Chip, who while not terribly clever, is cheerful, outgoing and good in bed, all traits she recognizes as alleviating her own mordant temperament. Her career amounts to little more than a knack: "The Stanford MBA was pretty much a sleepwalk through the borough of Lazy Ass."

Fortunately, Deb, like Chip, is in her own way not that difficult to please. She's content, more or less, if she can avoid the more sentimental and "pedophiliac/infantile" excess of wedding tradition: "A shower of any kind seems like a place for brain deficiency -- women squeal during those showers, squeal at the sight of trivial objects. A bridal shower features frilly underwear to make the new wife look more like a prostitute; a baby shower peddles frilly bonnets you drape around a newborn's face to make it look less like a garden gnome." She'd also prefer minimal interaction with her mother-in-law to be: "Chip believes she's cute and funny and should be humored smilingly. Most other humans tend to see her as more of a wrinkled mythological harpy, old, partially digested worms smeared over her clack-clacking beak."

Those first few chapters are some of the funniest in the book (although it's difficult to convey their deadpan wit out of context). But the novel's plot doesn't take off until the newlyweds arrive at a tropical island resort for their honeymoon. The resort functions much like the big country houses in Wodehouse's fiction, as a pot into which a motley assortment of characters get tossed, most of them irksome to the narrator and even the more agreeable ones likely to lure the hero into some farcical scrape. Deb accidentally engages the interest of a foot fetishist and endeavors to keep the gregarious Chip, who has a penchant for extreme sports, from getting mixed up in anything too dangerous. The one fellow guest she likes, a marine biologist named Nancy, enlists the couple and several other volunteers to witness real, live mermaids inhabiting one of the island's reefs.

The plan is to get the mermaids set up with the protected status of an indigenous people, but before the impromptu team can put it in motion, Nancy turns up dead under suspicious circumstances and her video evidence of the discovery vanishes. It soon becomes clear that the multinational company that owns the resort, aided by the island's police force and military ("a whole-owned subsidiary" of the multinational), wants to capture the mermaids and transform the island into a lucrative tourist attraction. Deb and Chip join a tiny group of holdouts (others include a former Navy SEAL a little too eager to deploy his explosives skills, a Japanese TV personality who can muster a digital-media strike force of teenagers, and a pair of neurotic, aging hippies) determined to thwart the takeover.

All sorts of capers and gambits ensue as the ragtag band of rebels tries to outmaneuver the superior forces of ruthless capitalism. Deb is hard-pressed to keep her new husband in one piece, what with "an ex-Navy father figure with a bomb" on board: "From now on, acts of terrorism and violence are a family decision, OK, Chip?" This could be a larkish Carl Hiaasen yarn, but Millet's humor is less broad, more quirky and offbeat; there's a running joke about a resort official Deb particularly resents because she first appeared wearing a long floral dress that makes her look like a Mormon, only to turn up later in shorts, her legs waxed. "It came to me," broods Deb, "that dressing badly could be seen, in a way, as a form of disinformation, a form, almost of psychological weapon."

For all its superficial resemblance to a Hollywood-movie scenario, "Mermaids in Paradise" is really a slapstick variation on Millet's abiding theme: the relationship between human beings and the natural world, especially animals. The way we regard animals is fundamentally unstable; sometimes, in both our stories and our lives, we treat them as persons, of a kind. At other times, we treat them like things. We love our pets as surrogate children, but when it suits us, we blithely eat the flesh of cows and pigs. (Except for those of use who refuse to do either, but still may not hesitate to swat a mosquito.) The mermaids embody that contradiction. Deb and company see them as people, but the multinational wants to herd, pen and exhibit them like zoo animals.

Millet is what's conventionally called a "serious" writer; her work is formally adventurous, literary in style and her short story collection "Love in Infant Monkeys" was short-listed for the 2010 Pulitzer Prize. But unlike a lot of literary writers, she's not afraid to make us laugh. In fact, there are times when you look at the way human beings conduct themselves in this world, and honestly, what else can you do?

Shares