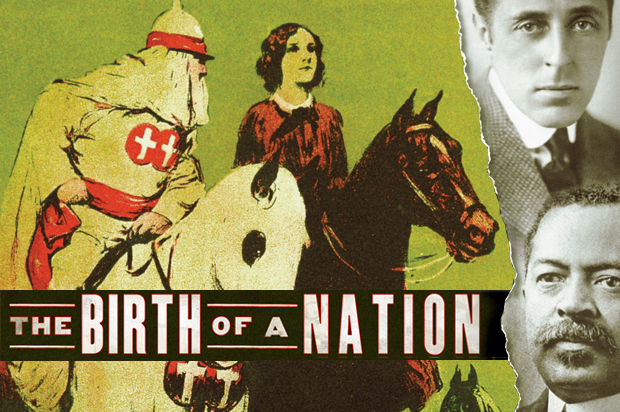

The morning of Saturday, April 17, 1915, the Boston Post published the final installment of a six-part series about the Lincoln assassination, a retelling that served to honor the slain president and his presidency. The last part was titled “Reconstruction—After Lincoln,” The article’s muted tone, its measured history of freed slaves and their political rights, the northern “carpetbaggers,” the public corruption that followed the war’s end, and the rise of the KKK and southerners’ “reclaiming” their states after the withdrawal of federal forces by 1877, was in stark contrast to the passionately pro-South rhetoric and anti-Negro story showcased daily at the Tremont Theatre in the form of D. W. Griffith’s epic The Birth of a Nation. The article concluded, “Marked by more turbulence, more retaliation, more bitterness than Abraham Lincoln would have countenanced, the reconstruction was at last accomplished; 4,000,000 slaves were free; the seceding States had again been brought into their proper practical relations; the Union was secure.”

Meanwhile, around the corner from the Post’s offices, Monroe Trotter was recovering from the previous night’s frantic scramble to put the latest issue of the Guardian to bed. Not surprisingly, the issue hot off the presses that Saturday morning was devoted to the Boston film war. Under the masthead ran the banner headline “Fight Against Birth of Nation Continues.” Stories on the front page and inside the paper rounded up the week’s developments— coverage that included reprinted news stories that had appeared in the daily papers; opposition letters. such as the one J. Mott Hallowell had written after seeing the movie; and reports of the pivot in protest strategy from City Hall to the State House, where Trotter and Boston NAACP officials were hopeful Governor Walsh would join their cause.

Then, around midafternoon, a letter arrived, containing the mayor’s response to the resolution passed Thursday night at the church rally that had called on him, once again, to stop the film. In it, Mayor Curley curtly reminded the editor “there is no way legally” for him do anything, “until such time as the State Legislature changes the existing law,” as well as that he had nonetheless done what he could to help, which was to request that Griffith to modify the movie. For Trotter, it was as if the resolution had been his way of giving the mayor a last chance to do the right thing, as he first had contained his own shock at Curley’s ruling following the hearing and then contained the hissing on Thursday night. But this correspondence reiterating a virtual do-nothing position was a breaking point.

The litany of grievances against the Griffith team was growing, not shortening. All week long, Trotter and other opponents had fielded complaints about illegal discrimination at the box office. Just that morning, his friend William D. Brigham described his experience with the “color line” when he had gone to see the film the night before. Brigham, who was white, watched as the ticket seller told a Negro in line ahead of him that the only seats remaining were the pricey two-dollar seats. Unwilling to pay that much, the Negro turned away and left. But when Brigham stepped up to the ticket window, he was told plenty of the seventy-five-cent seats were still available. In addition, there was the matter of the alleged cuts that Curley kept asserting he had secured and seemed so proud of. To Birth’s opponents, nothing substantive had been altered. Worse, to Trotter, who had seen the movie at the Tremont during the past week, the many objectionable scenes had “been enlarged rather than reduced.” It was as if Griffith was mocking them all—the protesters, the city, Curley—and latter in his reply had seemed to be dodging reality with words signifying nothing. Curley might be willing to play Griffith’s fool, but Monroe Trotter certainly was not.

W. E. B. Du Bois had rightly and enthusiastically noted Boston was the center of the protest action, even if back at NAACP headquarters, at least one key official was discouraged by the way things had gone the first week. “I never believed myself that this thing would be shown in Abolition Boston,” May Childs Nerney said on Saturday, the same day Trotter received Curley’s dismissive response. Further, she was incredulous that The Birth of a Nation was being shown there without any demonstration what-so-ever against it. Nerney, of course, had no way of knowing that within hours of writing a letter with those thoughts, this would change. Word was going around in certain quarters of Boston during the fading light of the early spring day, and around six p.m., the telephone rang in the newsroom of the Boston Globe on Washington Street. The anonymous caller was a “colored woman” (the newspaper never explained how it identified the woman’s race) and who advised the newspaper to hurry and dispatch a reporter over to the Tremont Theatre a few blocks away.

“There might be something interesting happen [sic],” she said.

* * *

It was around 7:15 p.m. and nearly dark when Monroe Trotter walked down Tremont Street to the Tremont Theatre, located across from the Boston Common at its southeast corner and near the Boylston Street intersection. Having been alerted beforehand, reporters from Globe and the other dailies had already arrived, and what they saw was wave upon wave of Negroes joining the civil rights leader as he approached the front of the theater. They came from every direction, and estimates varied, with some reporters putting the gathering of “colored men and women” at about two hundred, while others said the number was closer to five hundred. Either way, journalists agreed that over the next couple of hours, the crowd continued to swell until about two thousand people had turned out. Nearby in the compact Theatre District, movies and stage plays of all kinds were playing at the four other cinemas and the fifteen-odd theaters. Tillie’s Punctured Romance, for example, a comedy featuring Charlie Chaplin, had audiences in stitches at the Bowdoin Square Theatre, while Paramount Picture’s The Eternal City, a melodrama set in Rome, was being shown at the Boston Theatre. But nothing in town compared to the spectacle at the Tremont where, with that night’s performance set to start at 8:10 p.m., the marquee lights in front were ablaze. In making his approach to the theater, nothing appeared out of the ordinary to Trotter. Even the sight of uniformed Boston police officers was not a surprise; since the film’s opening the past weekend, the theater had paid for a special detail of up to ten officers.

In fact, though, preparations for the current screening were very different. The Boston police and Tremont manager Schoeffel had both received information that trouble was brewing. Police superintendent Michael H. Crowley never disclosed his source’s identity but said that during midafternoon, a reliable informant had warned of about a possible disturbance, and so he immediately ordered the day shift from the district station around the corner on Lagrange Street to stay on for special night duty, as well as summoned officers from nearby stations to assist them. Schoeffel said another theater manager had called him with word of a plot “arranged by a certain gang of colored men to raid the theatre and destroy the film.” At 4:30 p.m., Crowley had laid out for Schoeffel the beefed-up security plan he had devised, assigning more than sixty policemen to take up seats inside, dressed in plainclothes, with another complement of one hundred uniformed officers out of sight and on standby at the nearby station, ready for action.

By the time seven o’clock approached, or just before Trotter arrived at the theatre, Crowley’s forces were in place. Some occupied the entire first row of seats in front of the orchestra pit. Their assignment was to block anyone from reaching the movie screen. Others guarded the operating booth, with a few from that contingent responsible for protecting the wire leading from the booth into the cellar.

The remaining plainclothes officers were scattered in the first and second balconies, the gallery’s reserved section, and in the front lobby. Trotter detected none of this—all he saw was the typical detail of ten or so patrolmen milling about.

Then, with the arrival of what one reporter described as a “large body of colored men led by William Monroe Trotter,” Schoeffel did two things. The first was to make a quick telephone call to notify Crowley. The second was to order suspension of ticket sales for that night’s show. The only tickets to be issued from the box office, said the manager, were to patrons who had reserved them in advance. The goal was to impose a lockdown of sorts in the lobby; yet despite the order, box office employees continued selling tickets—and they did so discriminately. Mrs. Mary E. Moore, a Negro housewife from the Roxbury neighborhood, was rebuffed and then watched in disbelief as the white woman next in line purchased a ticket. Another white woman who had witnessed the disparity stepped forward and bought two tickets. She turned and handed one of hers to Moore. When People’s Baptist Church pastor Puller tried to buy a ticket, he was told, “Nothing doing.” By now Trotter and his followers had piled into the lobby, ignoring calls that they show their tickets. Crowley also appeared on foot from the station just minutes away, accompanied by a police captain, and saw the lobby was jammed to capacity. Outside, too, the crowd continued to grow—comprising mostly film protesters, Crowley said later, but also including curiosity seekers eager to observe the commotion. Immediately the superintendent called the police station. “Get ’em all down here,” he barked. People in the lobby continued to clamor for tickets. In reply, theater employees announced the show was sold out, that “the ticket rack was clean and they could not even sell any more stand-up admissions.” But Trotter and everyone else saw this was a canard, as white patrons were still being ushered inside.

Surrounded by supporters, the Guardian editor began pressing forward to reach the ticket window. Although far outnumbered, the police on hand ordered everyone out. “We won’t leave,” Trotter said. “We demand our rights to buy tickets.” Schoeffel said later that he heard Trotter yelling that if the movie could not be suppressed through legal means, it would be shut down by force. Police accounts said it was a man standing near Trotter who next shouted, “If we don’t get justice from the white man we will take the law into our own hands.” For his part, Trotter was determined to confront the ticket seller, arguing that if the show was sold out, then why not post a sign outside saying so. “I demand my rights,” he said, holding up a half-dollar and insisting the box office employee sell him a ticket. “You are selling to white people,” he roared.

Around 7:30 p.m., police reserves arrived from around the corner—more than a hundred men “on hand in a twinkling,” as one reporter wrote, and the action accelerated quickly. Crowley ordered the officers to clear out the lobby, and that was when the pushing and shoving began. Police, targeting Trotter as a ringleader, tried to move in on him, but supporters, many of whom were women, had encircled him as his bodyguard. The lobby was suddenly a thick, rocking mass of protesters and policemen, jockeying elbow to elbow. Amid all of the noise and confusion, the officers were having difficulty getting to Trotter. Dennis Harrington, dressed in plainclothes and appearing to be a civilian, wiggled his way close to Trotter and tried to seize him. When Trotter pulled away and would not budge, Harrington slugged him in the jaw. The assault stunned Trotter and seemed to freeze those around him in place, creating a kind of pause that other officers exploited to rush in and grab hold of him.

Boston Police sergeant Martin King and a second officer wrestled with Trotter, who struggled to hold his ground but was no match for his larger, stronger opponents. The editor demanded that police arrest the man who had punched him but was told they would not—because he was a policeman, too.

Outside, Trotter saw not only hundreds of protesters all around but also cordons of police—the majority of nearly two hundred officers now on the scene were lining the sidewalks to keep them clear. Most protesters were assembled on Boston Common across Tremont Street, contained behind a wall of police to prevent anyone from getting near the theater. Trotter could hear shouts of support along with angry denunciations of the police and the film, but he also heard scattered racial epithets and cries of “N—er.” Although the protesters never broke through the police line en masse, for the next several hours they hung around, defying officers’ attempts to make them move on. The time immediately following Trotter’s arrest was tense, turbulent, and seemingly on the verge of a race riot. At one point someone in the Boston Common crowd threw a projectile that barely missed hitting an officer, but when police rushed over they could not tell who had done it. When a newspaper photographer took a picture, the camera’s sudden pop and flash of light was mistaken for gunfire, and women screamed.

* * *

Held tightly by his captors, Trotter saw not only the one police cordon across the street but another that snaked around the corner intersection toward the district police station on Lagrange Street. Two officers had fallen in behind as a rear guard for the cluster pulling him along. Because they were stronger and taller, he had trouble keeping up, and he was being partly pushed and partly dragged down the street past the two lines of armed guards on each curb. Trotter squirmed and complained, “If you let me go, I’ll go along.” Despite the large show of force, several of his supporters broke through the line and ran ahead toward the police station.

With Trotter’s arrest police had secured the lobby, and they barred anyone, including the press, from entering from that point on. The film, even with all the disruption outside, was able to begin basically on schedule. But some protesters had made it inside the darkened theater, either entering as ticketholders beforehand or slipping past police during the commotion. Their shouts and complaints were heard periodically throughout the screening, especially after the start of the film’s second part, Griffith’s rendering of Reconstruction that was chock-full of racist content. One protester was a twenty-six-year-old Boston man named Charles P. Ray, who had smuggled in eggs and four small boxes containing “odiferous bombs.” Seated in about the tenth row, he managed to toss a few of his stink bombs while remaining undetected by the plainclothes police seated among the audience. But no real protest action made much headway during the screening, due to the suffocating police presence.

When the movie ended around eleven p.m., however, another round of trouble ensued. In addition to altercations between protesters and police, the night’s large-scaled demonstration also featured an occasional shouting match between groups of Negroes and whites, although no arrests resulted from confrontations occurring before and during the film’s screening. Instead, around 11:30 p.m., or more than four hours after the protest began, the scene at the theater started winding down, as the crowd thinned and headed home. In all, eleven people—ten Negroes and one white—were arrested, and most observers and reporters heaped kudos on police for smothering a situation seemingly primed for spontaneous combustion. “With all the makings for a real race riot at hand serious trouble was averted, and at last the crowd died away,” said the Boston Globe.

Nearly missed, however, was an outburst of true bloodletting— perhaps because of its later timing and its location away from the theater. Around midnight, or thirty minutes after everything had died down, three Negro men who had left the Theatre District and were walking home to Roxbury clashed with a group of white men who were also at the protest. Police responded quickly to reports of a brawl in progress, but not before the Negro men, each carrying a razor, had wounded four white men. The injured were taken by ambulance to Boston City Hospital, where they received stitches for lacerations on their neck and treatment for abrasions on their head and body. The Negroes were jailed on charges of assault with knives, and, when searched, one was found to be carrying a loaded, .38 caliber pistol in his pocket. Only two of the seven daily newspapers managed to learn about the bloodshed in time to include a brief sidebar story in their Sunday morning edition.

“Race Riot in the South End,” was the Boston Post’s headline. The article continued, “Two hundred police officers battled the crowds in the lobby and on the streets, before and after the show.” “As a racial demonstration probably nothing like it has been seen in Boston since the Civil War,” reported the Boston Globe in its front-page story.

Excerpted from “The Birth of a Nation: How a Legendary Filmmaker and a Crusading Editor Reignited America’s Civil War” by Dick Lehr. Published by PublicAffairs, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright 2014 by Dick Lehr. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.