For better and for worse, the civil rights movement is at the forefront of American culture right now. And after the non-indictment of Darren Wilson for the killing of Michael Brown predictably (and, perhaps for Wilson's supporters, conveniently) inspired riots in Ferguson and elsewhere in the U.S., the question of when disobedience is justifiable — and what form of disobedience is justifiable — became relevant in a way it hadn't been for years, or even decades. No less a figure than President Obama reportedly touched on the issue during a recent meeting with young, minority activists.

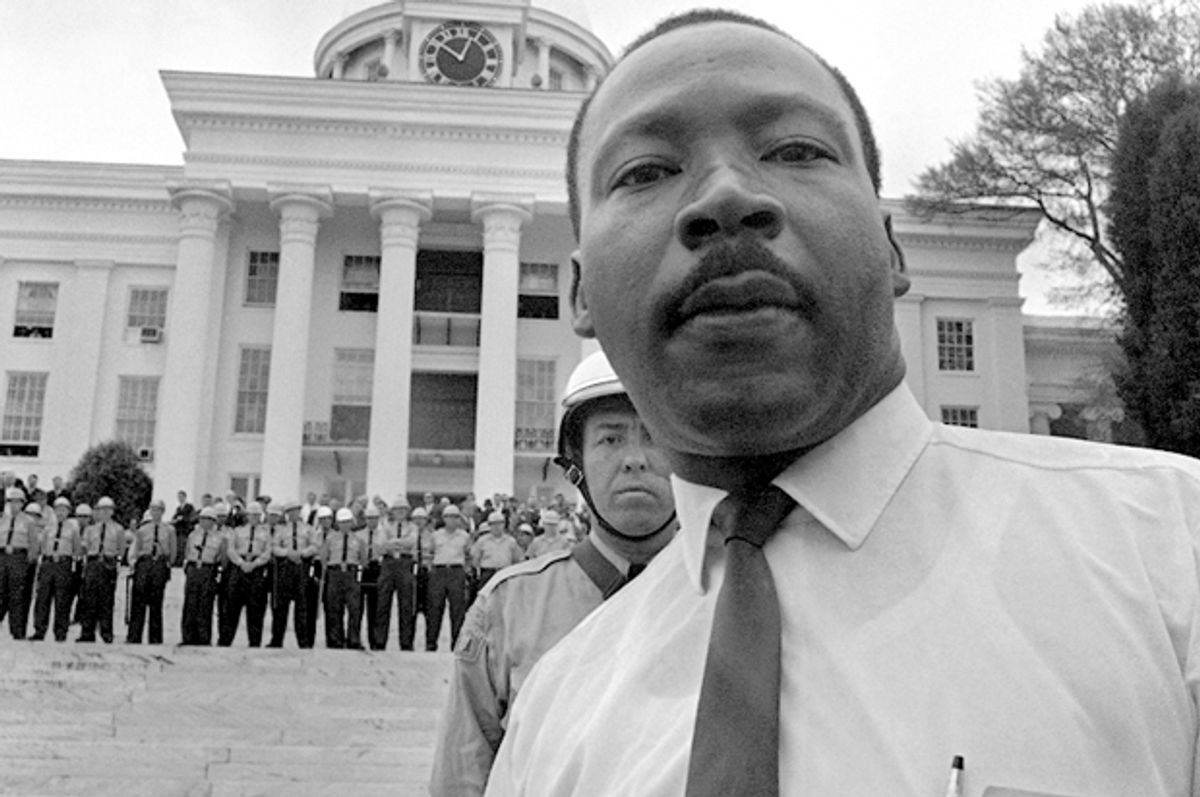

So with King's legacy being claimed by both protesters in Ferguson as well as their critics, we wanted to speak with Stanford historian Clayborne Carson, who runs the university's Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute and who in 1985 was entrusted by Coretta Scott King to publish and edit the reverend's papers. We talked about King's legacy, the role he played in the broader movement for human rights and what many people misunderstand about nonviolence. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

How do you feel about the connection a lot of people are drawing between what’s happening right now in Ferguson and the civil rights movement? Is that a useful frame? Or is it too pat?

I think it’s always useful to have a larger historical frame in which to put what’s going on at the moment. For me, the framework is the gradual movement toward universal human rights. I think of it basically as three stages: We have these great international movements to first abolish slavery, then the movements for equal citizenship rights, which culminated in the 1960s, and now we’re in another stage. It’s quite clear, as it was to MLK at the time, that the civil rights acts of the mid-1960s were a wonderful victory but they were not sufficient, that they were not going to solve the problems of black Americans any more than ending slavery solved those problems.

So King knew that the job wasn't finished. The mainstream narrative of the civil rights movement tends to imply the opposite — that the civil rights bills passed in the '60s represented a more permanent victory.

I think one of the aspects of King’s leadership and Malcolm X’s leadership is that they both were skeptical about civil rights reform. Malcolm X as a black nationalist — well, of course he’s skeptical that the country that had oppressed us would somehow free us from that oppression. King, I think, just felt that it had to move toward broader goals, which he outlined in 1964 as his Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged. Those people are the movement — and I consider myself one of those. We didn’t stop what we were doing because the Voting Rights Act was passed or the ‘64 Civil Rights Act was passed; I think most of us understood that it was going to take more radical changes to really free us from oppression.

Right — changes that haven't happened.

We’re still answering King’s final question, and that is, “Where do we go from here?” I see the last 50 years as an attempt to answer that. I think when you look at so many of today’s problems, they all relate to our sense of disappointment that even 50 years after the passage of civil rights legislation, we’re still not secure in our life, liberty and pursuit of happiness. We still face some real challenges, which, for me, were unexpected, but I think if King were around he’d say, “Well, I warned you.”

If he were alive and active today, how do you think Dr. King would respond to the property damage and looting in Ferguson — especially as it’s depicted in the press? There have been some attempts to contrast what's happening now with what King did in the '60s — how would he feel about his legacy being used that way?

I think he would resent the way in which he is used as a symbol to reduce the anger that people feel. I think he would always make the argument that nonviolent resistance is better than violent resistance. To me, that seems obvious; if the person or institutions who are oppressing you are more powerful than you are, using violence will not get the result that you want. You have to use some other means. That’s one of the innovations of the 19th and 20th centuries, that people who are oppressed used their imagination and creativity to develop a set of tactics and strategies that succeeded in overcoming the most powerful forces in the world.

Gandhi went up against the British Empire at its height; King was working in the most powerful country of his time; Nelson Mandela was acting in the most powerful African nation. I’m using these people as symbols; obviously, they represented mass movements, but in each of these cases there’s no way the mass movement could have overcome the source of the oppression [with violence]. South Africa had atomic weapons and so did the United States; there’s just no way that violence can do anything more than be an expressive tool. It can’t be instrumental, it can’t really be effective except in rare circumstances, where governments have lost their legitimacy among the masses of the people in the country. What happens with violence is that it strengthens their legitimacy. If you use violence, it just means that governments become more powerful — because now they have an excuse.

Your point about the strength of the government reminds me of something the Atlantic's Ta-Nehisi Coates tweeted, which is that those telling protesters to be more like King aren't really acknowledging what King's life was like. After all, this is a guy that the government surveilled, threatened, harassed, brutalized —

— And who organized, at the end of his life, what I would consider the most radical Occupy movement of the 20th century. When you think back on all the criticisms of the Occupy movement, none of them propose anything as radical as what King proposed in 1968, of going and occupying the National Mall. I think those who argue that the protesters in Ferguson should be more like King — be careful what you wish for. If all the people there in Ferguson had King's vision, and, more importantly, if people everywhere had his vision of not only a more peaceful and just America but a more peaceful and just world ... Well, first of all, that’s a radical vision; but it’s also a disruptive vision, because we’re not going to get to that peaceful, just world by working within the system. The system is what perpetuates an unjust world, and a lot of what we identify as the system is going to have to be fundamentally changed in order to achieve any kind of just world.

Obviously, one of the things I hope is that people actually read King; not just the “I Have a Dream” speech but all of his writings and speeches and sermons, even. They would hopefully come to a new understanding that he was a radical. He was someone who tried to identify the root of the problems confronting us and tried to envision a world that is quite different from the one we have. I think that would make King more of an attractive guide for people who are discontented. King gave his life to try to make life better for those who were less fortunate; he saw that as his mission in life. He was a social gospel minister, and so I think the idea of a King who was a martyr for the cause of social justice and peace in the world needs to be put forward as a kind of leader worth following today. He has a lot to say about how we should deal with our problems in the present.

It is frustrating when you see King used as an argument for complacency, essentially. You realize that that’s just a misunderstanding of the person I’ve spent the last three decades studying.

It seems to me that the difference between violence and disorder gets elided sometimes, with one of the results being an impression that Dr. King's protests were somehow orderly and not disruptive.

I think most of the problem comes from the use of the term “nonviolence.” Most practitioners of nonviolence have raised questions about the categorization of the term, because it says what you cannot do but it doesn’t say what you can do. I always combine the term “nonviolence” with “nonviolent resistance” and you’re resisting injustice. Someone who says that they’re practicing nonviolence by simply not engaging in resistance to injustice … it’s a false use of the term, and it doesn’t reflect the legacy of MLK or Gandhi or Nelson Mandela. It’s just an excuse for inaction.

If you actually practice nonviolence, the time to do it is before it gets to the Ferguson stage. That’s almost the last stage of it, when the injustice has already angered people to the point that some of them do lash out in violence, because they haven’t been shown the effectiveness of nonviolence. People who believe in nonviolence have to demonstrate its effectiveness on a continuing basis; they can’t wait until a situation is completely out of [control] and then recommend nonviolence. People haven’t been shown that nonviolence is effective, and that’s a continuing lesson.

So what's the better way to engage in nonviolent resistance?

I think to practice nonviolence you have to think about what is the ultimate goal. What is it trying to achieve? And that goal should be something that is worth fighting for, that is worth mobilizing people for, that’s worth starting a movement for.

One of the differences between now and previous movements — getting rid of slavery was something where you could mobilize people around the world. You could make the argument that this is immoral and it should be abolished ... The same thing happened with the Jim Crow system and with various kinds of racial discrimination, and with colonialism. We were able to overcome the Jim Crow system; we were able to overcome colonialism; and part of what made those movements effective is that there was a clear goal. It might be difficult to achieve and it might take decades to do it ... I think of someone like W.E.B. Du Bois, who was born after the end of the Civil War and died on the eve of the March on Washington. He lived 90-something years and never saw the great victory.

I think that’s why it’s so important to have in mind this goal of universal human rights. Again, it might take 50 or 100 years to get there — but it's something we’re fighting for. It’s something that helps us clarify why there is systematic injustice in the world and what it would take to eliminate a lot of that.

Shares