Jealousy, common at work, has an unexpectedly close relationship to creation. Like family jealousy, this is not much admitted to, even by the sufferers themselves, but it appears and reappears in mythological stories. Perhaps it’s through these that the human anxiety surrounding this uncomfortable emotion is best enunciated.

A lesser-known story concerning Daedalus, the mechanical engineer and inventor who created the wings for his overambitious son, Icarus, is instructive. In his Metamorphoses Ovid describes how, after Icarus’s death, Daedalus took on his sister’s son, Perdix, as an apprentice. The boy was as good an inventor as Daedalus. In no time at all he’d devised the world’s first saw and the first pair of compasses. This was too much for his uncle:

‘In jealous rage his master hurled him down / Headlong from Pallas’ sacred citadel’. Daedalus tries to do for Perdix what Icarus did for himself, because he did not follow his father’s advice. Both boys fall because, in the eyes of Daedalus, they overstretch themselves. Neither, in different ways, heeds the superiority he insists on when it comes to invention. ‘Master inventor’ was the position that Daedalus jealously guarded. Luckily (or unluckily) for Perdix, Pallas catches him and transforms him into a partridge (perdix in Latin). As Ovid says, ‘this bird never lifts itself aloft, / . . . dreading heights for they recall / The memory of that old fearful fall.’

Daedalus and Perdix are locked in an intergenerational jealous battle between teacher and pupil, as are Athena and Arachne. Ovid’s Metamorphoses is again the source of this chilly tale. The goddess Athena taught Arachne spinning and weaving. Arachne became very good at it, so good that ‘often to watch her the nymphs would leave their own vineyards on Tmolus’ slopes, and the water nymphs of Pactolus would leave their waters’. She denied the goddess Athena had had anything to do with it, and ‘took offence at the idea of such a teacher’. Athena was furious that a mere mortal should presume to deny a god her dues. Bold Arachne simply challenged Athena to a contest in weaving. The offended deity gave Arachne a second chance, disguising herself as an old crone and advising her to ‘seek all the fame you will among mortal men for handling wool; but yield in place to the goddess’. Arachne responded arrogantly: ‘Why doesn’t your goddess come herself? Why does she avoid a contest with me?’ Athena threw off her disguise at once and the contest began. Athena’s tapestry depicted the power of the Olympian gods and the punishments suffered by human beings who were arrogant enough to challenge them. Arachne, soon to earn just such a fate, chose to create a tapestry prophetically depicting the suffering of humans at the hands of jealous gods – including Europa being deceived by Athena’s father, Jupiter, who, disguised as a white bull, abducted her and raped her, which can be seen in the background on the right of Rubens’ painting. Who won? Ovid tells us that ‘Not Pallas, nor Jealousy itself [Livor, in the Latin, accompanies Athena] could find flaw in that work’ by Arachne. ‘The golden- haired goddess was indignant at her success, and rent the embroidered web with its heavenly crimes; and, as she held a shuttle of Cytorian boxwood, three times and again she struck Idmonian Arachne’s head.’ Arachne couldn’t take this beating, and slipped a noose around her neck, but Athena took pity on her, after a fashion, and transformed her into a spider. ‘Still from this she ever spins a thread; and now, as a spider, she exercises her old- time weaver- art.’

Some have claimed that Arachne is Ovid and that this story is a fable about the difficulties he experienced in his own creative life. What the story does show is that the older, established generation can be just as jealous as the younger newcomers. Jealousy cuts both ways, and it is centred on both the position as ‘the creator’ and the act of creativity.

There are many examples of this kind of intergenerational clash between creators. One example of the younger lashing out at the older concerns Michelangelo and Leonardo, who felt ‘an intense dislike for each other’, according to Vasari, their biographer. The only evidence we have to go on is an altercation in the street. Leonardo beckoned Michelangelo over to explain a passage in Dante. He is supposed to have replied, ‘No, explain it yourself, horse-modeller that you are, who, unable to cast a statue in bronze, were forced to give up the attempt in shame’, then he turned his back on them and walked off. ‘Leonardo remained silent and blushed at these words.’ Was Michelangelo’s abuse of the world’s greatest genius motivated by jealousy? Leonardo crafted an equestrian statue for the Duke of Milan in clay but never cast it in bronze. It was meant to be the largest equestrian statue in the world. When Michelangelo went big – there are few artistic projects bigger than the Sistine Chapel ceiling – he made sure he finished the job.

Going the other way, an example of an older creator jealously protecting his position is the legendary antagonism between Salieri and Mozart. In the 1780s Salieri was the more established in Vienna and apparently he and the Italian cabals obstructed Mozart obtaining certain posts or staging certain operas. Salieri is even rumoured to have tried to poison Mozart. Alexander Wheelock Thayer puts the rivalry down to Mozart being overlooked in favour of Salieri to be Princess Elizabeth of Württemberg’s music teacher. It seems that after Mozart had made a name for himself in Vienna, the two men supported each other’s work, but that didn’t stop plays, operas and films dramatizing Salieri’s insane jealousy.

But there is also a sense in which creative jealousy could be beneficial – or at least necessary. Harold Bloom’s The Anxiety of Influence (1973) argues that there exists between outstanding writers of different generations a profound but fructifying jealousy. Great writers, according to Bloom, sense a strong relation to tradition and their forerunners’ works and engage in a strong misreading, or a creative reinterpretation – a killing and a superseding, as it were – of that original material. It’s a kind of literary Oedipus complex. Bloom describes it as ‘a profound act of reading that is a kind of falling in love with a literary work’. The greats – Shakespeare, for instance – ‘will not allow you to bury him, or escape him, or replace him . . . The largest truth of literary influence is that it is an irresistible anxiety’. The anxiety comes from not knowing whether you can be better than those great predecessors. Whether you agree with Bloom or not – and many writers would disagree, jealously guarding the idea of the unique imagination, the importance of their own development, or uncomfortable with the idea of labouring under this hierarchical canonising impulse – the theory is a powerful enunciation of the importance of jealousy in literary creation.

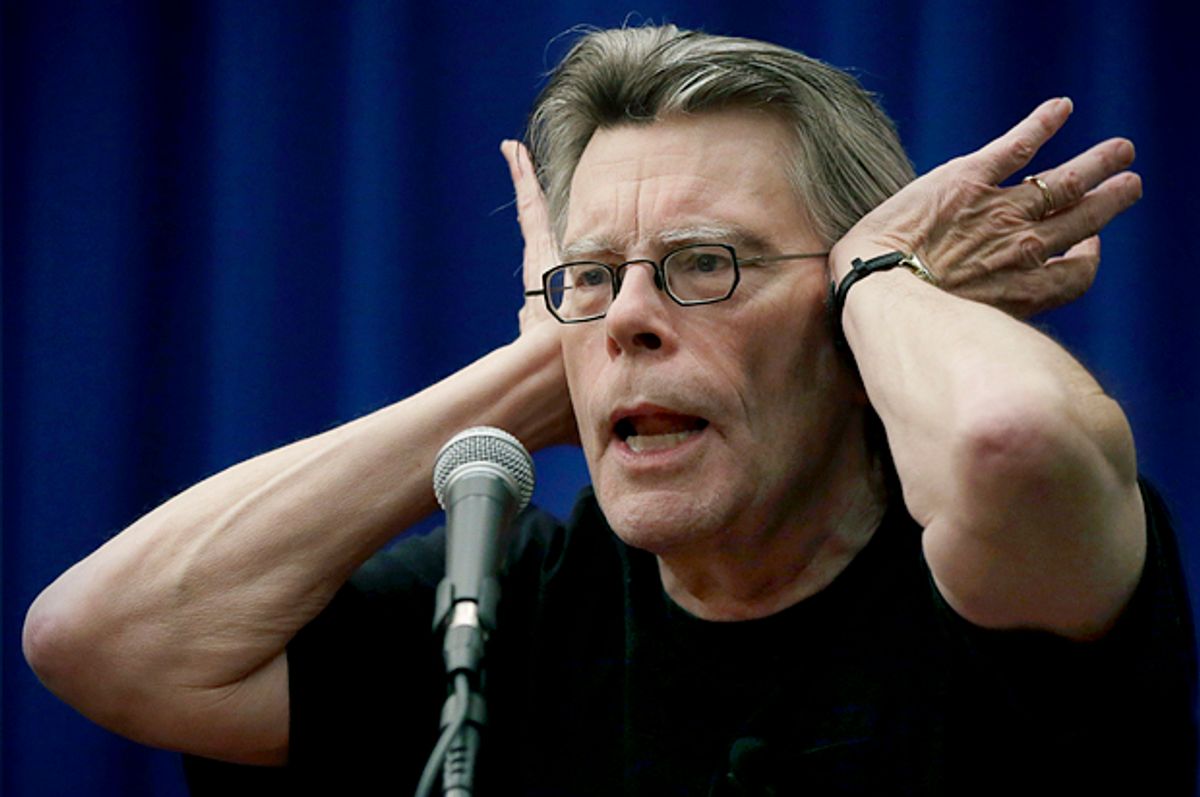

Creative jealousy occurs when an artist identifies closely with his work. Stephen King’s 1987 novel, Misery, shows that jealousy does not only occur between rival artists. This is a book about the jealousy of the audience. King’s book is inspired by John Fowles’ The Collector (and acknowledges the debt by referring to ‘John Fowles’ first novel’, and using a quotation from it as an epigraph). There is a house-bound captive in both books, though, like a good Bloomian, King misreads, accentuating not Fowles’ class jealousy and the uneven distribution of wealth in society, but the jealous triangle formed by a writer, his work and its readers, and the violent consequences of trying to break out of it.

Paul Sheldon is a successful popular novelist who has made his name with a series of books featuring a character called Misery Chastain. Sheldon resents the demands of his readership who insist he repeat the same old themes, themes that he has become very tired of. He kills Misery off, and his readers hate it. He has destroyed a valued relationship they had with their favourite character, and he whom until that point had been their favourite novelist. Paul himself is also jealous – of writers who have artistic freedom, who are able to change topic and theme with each book. He recognises that ‘he was Paul Sheldon, who wrote novels of two kinds, good ones and best sellers’, but hankers after an escape from this claustrophobic pigeonholing. (It is said that King derived the idea of Paul’s predicament from his own readers’ reaction to his book The Eyes of the Dragon. They wanted him to get back to the horror stories.)

When Misery begins Paul has just finished his latest book, Fast Cars, ‘a contemporary novel about a car thief ’. He crashes his car in the snowy Colorado Rockies. It is a premonition of what’s to come. He’s rescued by Annie Wilkes, his Number One fan, as she incessantly tells him, who feels bitter about the demise of Misery Chastain. There is a flash of jealousy on Annie’s part towards Misery’s demise. She wants Sheldon to write Misery back to life and she won’t free him from her basement until the task is complete. Paul eventually tries to escape from his basement scriptorium, and discovers that Annie is a murderer. To put an end to his wandering Annie chops his foot off with an axe. The amputation appears to focus Paul’s mind on the task. But Paul gets his revenge. He finishes Misery’s Return and tricks Annie into thinking he’s set fire to the manuscript. As Annie rushes to save the burning novel, he coshes her with his typewriter and she falls, hitting her head on the mantelpiece. He inserts the burning manuscript into her mouth, page by page. If ever there were a symbol of the jealous author striking back at his audience, that’s it. Eventually rescued by a second posse of police, Paul gives his publisher a saved copy of Misery’s Return. It might have been titled Arachne’s Revenge.

Disproportionate fan fury is not new. The New Yorker recently drew a comparison between Stephen King’s Misery and the video-game Mass Effect 3, the ending of which was so disappointing for its legions of fans that the game studio agreed to revise it. ‘It’s a staggering victory for the series’ most zealous enthusiasts,’ said the New Yorker, ‘and that, unfortunately, is the problem. As long as gaming’s “core fans” hold such sway over major game studios, art will never have a chance.’ Fandom communities’ boards are full of angry complaints about the current directors or writers of long- running TV programmes and how they are ‘ruining’ it. Like Paul Sheldon, the creator is getting in the way of the audience’s jealous relationship with the work.

Other times, it’s more personal. An audience’s sense of jealous ownership seems to be more and more a natural part of celebrity these days. Not only has the internet made it much easier for fans of, well, just about anything or anybody to come together as a group, it also breeds an intense and false sense of intimacy through interfaces like Twitter, Instagram and other apparently direct channels to the stars. Many fans now feel a sense of entitlement, or ‘fantitlement’, as christened a few years ago by Wil Wheaton, the actor who played Wesley Crusher in Star Trek: The Next Generation. This is the conviction of fans that their passion and dedication to a person grants them particular rights and privileges. Wil describes being mobbed by around fifteen fans who, instead of meeting him at the Comicon convention in 2011, had camped outside his hotel. He was surrounded, split from his friends and family, and understandably terrified. His friend pulled him out. ‘This is when the mob lost its shit. They yelled at me like I had done something wrong. They called me names, and they booed at me. (Seriously). A woman stormed up next to me and said, “If you don’t sign these things for me, I’m going to tell Twitter what an asshole you really are.” ’ As Wil says, ‘It isn’t about our work, or about saying “thank you” or “high- five!” or anything about that. It’s about entitlement and being crazy’. These superfans are certain their efforts should be rewarded and reciprocated, that their love creates an obligation on the object of their attention. It is like they are in a deeply jealous relationship with someone who doesn’t even know their name.

* * *

It might seem as though jealousy is taking over our modern lives. Are humans more jealous than ever before? It’s fair to say that the banking sector has been the workplace we’ve all had our eyes on over the last few years. Some commentators have pinned the glee over the collapse of greedy corporations like Lehman Bros, the on-going frustration about bonuses and inequality, and the tiny shifts in legislation that suggest a desire to start redressing the imbalance, as evidence of mass public jealousy. This particularly worries the conservative plutocracy in the US, which said for years that envy and jealousy don’t work in American politics, that its citizens admire the rich rather than begrudge them their fortunes and success. Now commentators are warning about ‘a national shift toward envy’, which, argued Arthur C. Brooks, president of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, ‘would be toxic for American culture’. If Americans are envious, God help the world. There is no doubt real and valid populist anger about fat cats, bank bailouts, tax avoidance schemes, big bonuses, shoddy self- serving management, and so on, but this is specific resentment. Labelling this sort of widespread feeling ‘envy’ or ‘jealousy’ robs it of its power, and exculpates the labeller: ‘What’s handy about making accusations of envy or jealousy is that it doesn’t have to reflect badly on you, the accuser. Hey, it can’t be helped if people are resentful – your success is your own and why should there be apologies for making something of yourself?

Thus, victimhood becomes the whine du jour of the superrich’, argues Michael Winship. ‘It goes well with everything.’ The public’s anger about such facts cannot be dismissed as a jealous anger. It is common sense.

Excerpted from "Jealousy" by Peter Toohey. Published by Yale University Press. Copyright 2014 Yale University Press. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares