During a recent appearance on "Meet the Press," former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani inspired days of criticism by telling fellow guest and Georgetown professor Michael Eric Dyson that his focus on police brutality was misguided. "We are talking about the significant exception," Giuliani said, referring to white police officers killing black people. "Ninety-three percent of blacks are killed by other blacks." Giuliani then went further, telling Dyson, "Why don’t [black people] cut [crime] down so so many white police officers don’t have to be in black areas?"

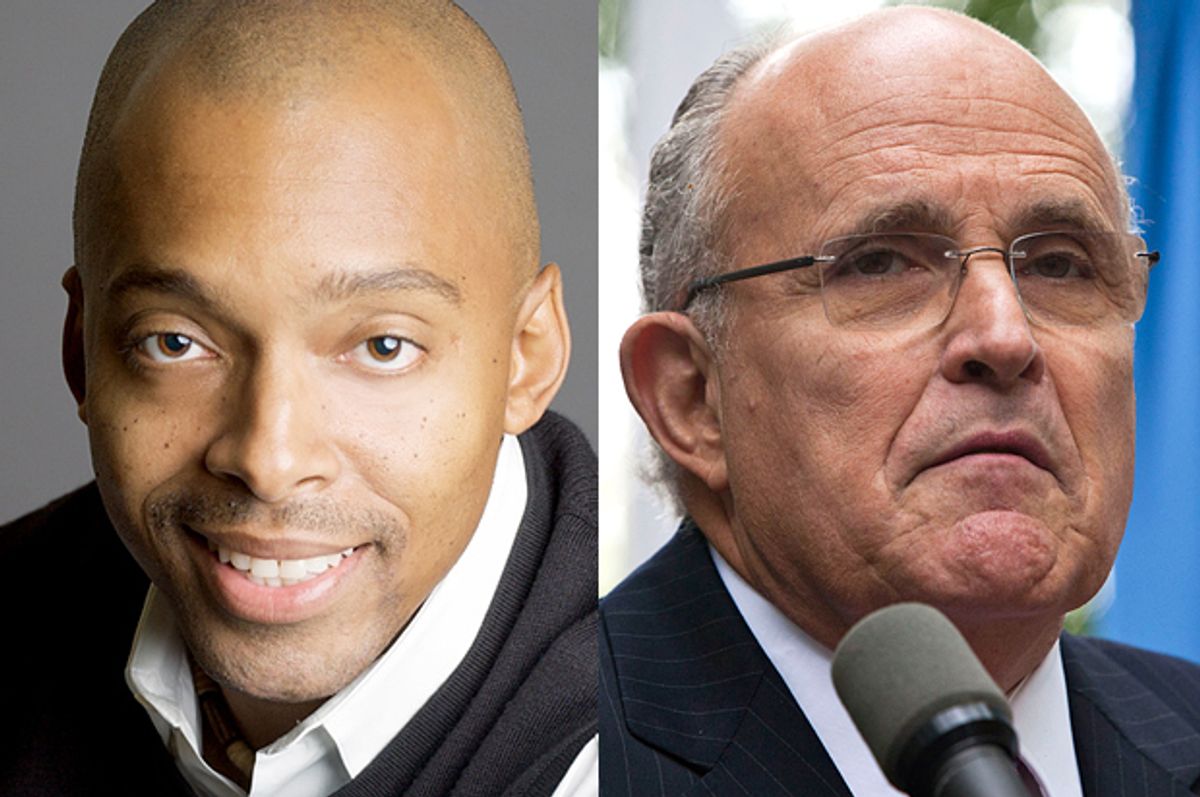

Except for Giuliani die-hards or unreconstructed racists (far from mutually exclusive), most people recognized the ex-mayor's comments as insensitive — at best. But while there's been criticism of Giuliani's use of crime statistics, especially his failure to note a similar figure is true for white killings, there's been less focus on whether these statistics themselves are as objective and reliable as we believe. With that in mind, Salon recently spoke on the phone with Dr. Khalil G. Muhammad, the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and author of "The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime and the Making of Modern Urban America," a widely praised study of the history of how racism and criminology have mixed.

Along with discussing the creation of crime statistics, we also touched on Giuliani's worldview as well as why the #blacklivesmatter movement is reason for nearly unprecedented optimism when it comes to combatting racism in U.S. society. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

Right after the decision not to indict came down for Garner, I got into an argument with a conservative friend who disagreed with the Staten Island grand jury's decision, but also agreed with the decision of the grand jury in Ferguson to exonerate Darren Wilson. I felt like that was a bit incoherent, because I considered them two parts of the same story. He disagreed and said it'd be better to view them in isolation. Do you agree with him?

No, I don't, though I'm not surprised [to hear he felt that way]. Part of what makes these patterns problematic is the isolation of instances of abuse as evidence of a single bad actor ... If we only see them as individual instances, then we are incapable of asking the much tougher question of whether it's a systemic problem as opposed to an individual problem. We're also incapable of having the kind of political debate about what is necessary to change this system.

Another argument I've heard from some conservatives, most prominently former New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, is that focusing on how police treat black people is a mistake, and that the real problem is "black-on-black" crime. He cited some statistics showing that, when a black American is killed, it's usually by another black American. Is that figure, and the use of these kind of race-based crime statistics in general, as straightforward as it sounds?

Racial crime statistics have a unique history that is tied to ... saying that black people's position in society is not a reflection of social or cultural forces, but a reflection of African-American behavior and cultural patterns. The crime statistics themselves were defined from the very beginning as a proxy for black people's humanity and their capacity to participate fully, or to be first-class citizens, in the United States of America.

That is their origin, that was the function and purpose of them; and, more interestingly, it was not unique to African-Americans in the late 19th century, when crime statistics became a useful measure of how particular groups were faring.

No? Did they used to break down different categories of people we now call "white," too?

Once upon a time, at the end of the 19th century, you could look at local arrest data and answer the question, how many Italians committed armed robbery last quarter? How many Irish committed burglary? How many Russians — many of whom were understood to be of the Jewish faith — were involved in bank robberies? You could do that in New York and Chicago and all of these places prior to the Progressive Era's attempt to reverse the way crime statistics were being used.

What happened during the Progressive Era that led to a change?

In the midst of a response to the massive inequality and poverty, underground economies and everyday crime and violence in overwhelmingly white working-class and European immigrant communities, liberals and progressives began to argue for structural responses to those indices of poverty and crime. What they argued was that the humanity of those people could not be measured in crime statistics but that social inequality could be. Crime statistics were symptomatic of inequality and structural disadvantage, of police violence and corruption as well as economic inequality, rather than the other way around. That culminated in the eventual erasure of white, ethnically focused crime statistics ...

When the federal government, by 1930, established the uniform crime reporting standards, which came to be known as the Uniform Crime Reports ... [it] moved from a category of foreign-born crime tracking to categories of white, foreign-born, Mexican, Indian, Negro, and other. Those other categories were not demographically significant and the primary comparison was between the white, the foreign-born and what was called the Negro. Soon thereafter, foreign-born disappeared, and ... all you're left with is a white-versus-black standard for measuring deviance and criminality in America.

So a system that the authorities eventually stopped applying to white people, because they thought it was unscientific and reflected more on economic and social factors than ethnic or racial ones, was kept in place for African-Americans.

Keeping track of black crime statistics is an artifact of a eugenics movement in American history, when we ranked races based on their fitness. To this day, essentially, the only group to never disappear into a normalized category were black people ... We have not moved past the way we use crime statistics for non-whites as evidence of non-whites having pathological behavioral patterns in America. It remains as true today as it was when this became the most significant measure of tracking these groups, in the late-19th and early-20th century.

And that's the foundation or framework that Giuliani is using when he starts talking about "black-on-black" crime and lecturing black people to get their house in order, as it were?

Right. The argument is also a 21st-century segregationist claim. What do I mean by that? No community ravaged by interpersonal violence at any point in our history ... [was healed] without the support of state actors — elected officials, representatives of the criminal justice system, etc. — as well as private interests, like chambers of commerce and philanthropic communities ... It's only in the context of African-American crime and violence that there's a notion that this is something black people have to fix for themselves before other people can help them, when, in fact, they don't have the same political or economic currency, or the connections, to leverage a moral argument that compels people to care about black children in ways they intrinsically care about white ones ...

We tell [African-American communities] to fix their own problems and yet, although they are the most in need, [they're given] the fewest resources. No group in American history has ever solved the problems that plague the African-American community, in terms of poverty and crime and violence, on their own. It's an absolute fact. When the poverty and crime in those white immigrant communities spilled out onto American streets and threatened the respectable communities of outsiders? All hands on deck. The response was a collaboration and coordination and decriminalization. To borrow a very common trope in our moment: When those communities were white, the problems were too significant to neglect, and the people in these communities were too significant to jail. The problems were too big to jail.

So what does it mean when Giuliani and others hold black people to a different standard? When they argue that there's a problem within African-American communities that only African-Americans can fix?

When Giuliani is raising those questions, he's essentially saying everything's fine in the nation-state except as it pertains to black people, rather than seeing black people as a barometer for something very sick in our society ... Someone today like Giuliani or Ray Kelly or [the Wall Street Journal's] Jason Riley — for these individual commentators, there is no critique of American society. For them, the evidence of criminality is not evidence of the greatest economic disparity the nation has ever witnessed ... For them, those realities of economic inequality today don't translate to black people in ways that we have empathy and understanding for (in terms of the challenges poor people face and the stigma we attach to poor people). You just have to be poor in this country to be presumptively suspect; and to be poor and black is to be presumptively criminal.

When the governor of Vermont is talking about the scourges of heroin and meth that have taken over impoverished working-class communities, by contrast, he's not saying we have a scourge of white-on-white crime and violence, or a scourge of white-on-white drug abuse. He's not asking what's wrong with white people. He's saying there's something wrong in the state — there's something wrong in our communities — that we all need to work together to fix. It works just the opposite in New York or Chicago or Philadelphia.

It seems to me like it goes further, too. In his debate with Dyson and during subsequent media appearances, he's not only argued that African-American communities should worry about their own problems instead of white cops killing their children, he's argued that the cops wouldn't even be there if black people weren't so violent — as if police misconduct was kind of their own fault.

I wrote a piece for the Nation and I quote a wealthy white suffragist in a conversation with the leading anti-lynching activist in the world at the time, a woman named Ida B. Wells. She was a journalist from Memphis and she moved to Chicago and was doing grass-roots organizing around issues of black poverty and anti-police and anti-lynching violence. Wells is having a conversation with a wealthy white suffragist about a recent riot in Atlanta that resulted in 30 black people being killed, hundreds injured, and no whites arrested. It was a pogrom.

So when Ida B. Wells is talking to the suffragist about the terrible things that had happened in the midst of the Atlanta race riot — Du Bois wrote famously about walking in the ashes of the Atlanta race riot of 1906, walking by a store and seeing body parts of African-Americans on display — the suffragist says to her, "The best way to end the scourge of lynching and race riots is to drive the criminals out from among you." And then she says something like, "Just last year here in Chicago, 10 percent of all crimes were committed by colored people; and they're only 3 percent of the population."

That's not her saying that black-on-black crime excuses police violence and vigilante white violence against black America, but that's essentially what she means. If it's true in ... the Jim Crow period, how can we be so comfortable that the same motivation doesn't underlie the practice now? That's the argument that many [#blacklivesmatter] protesters are making ... We have not, in fact, left this period behind on the issue of the capacity to murder in the name of fear of black people. Whether you are an individual white person or whether you are an individual representative of the state, it is just as legitimate today to say, "I was afraid!" It's as true today as it was in that period.

Yet despite all of these double-standards that are so entrenched in our society and state — even to the point that our way of tabulating crime is born in part from white supremacy — I saw that you recently wrote you were optimistic about the future. Why?

I'm optimistic because I think more people than at any time in my short life are open to these conversations and are willing to listen. I don't just mean the young people who have taken to the streets, whether they are white or black or Latino or Asian (because they're all represented in those protests and demonstrations). I mean that at every level that I'm participating in these conversations, people are willing to listen in ways that they have not been willing to listen in a generation.

I also think it has become painfully clear that, as my colleague [and Salon writer] Brittney Cooper says, respectability will not save us. In other words, people are beginning to recognize that this is not about being buttoned-up and having one's belt buckled tight. There is a fundamental cancer in the ways in which it is acceptable to express violence in response to one's fear of black people, from George Zimmerman to Darren Wilson. More and more people across more and more demographic categories are beginning to say that that's not acceptable.

Shares