Until a year ago we lived in south St. Louis on what might be called with some understatement a rough street. Pennsylvania Avenue is one of the high-crime “state” streets that lie a few miles south of downtown, a hot spot with an enhanced police presence where whites (and some African-Americans) tend to steer clear, even when slumming.

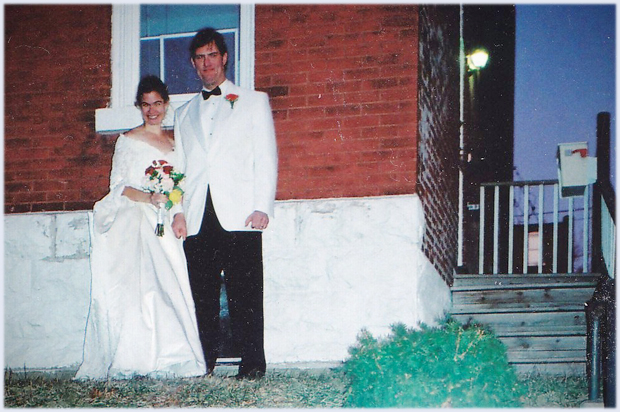

The presence of a seemingly middle-class white couple on our street was more than a mere oddity. Many nights my pickup was followed home by a suspicious police officer, his curiosity piqued by the sight of a middle-aged white guy cruising through the Gravois Park neighborhood. It was assumed any whites in that area were there for one purpose only – and it wasn’t to visit grandma. Down block after boarded-up block of red brick homes the patrol car tailed our pickup, creeping down our back alley before coming to rest behind our house, the spotlight trained on the wife and me as we carried our box of half-eaten Chicago-style to the house, trying to act casual, just a typical couple home from dinner. Nothing to see here!

We totally got the cops’ skepticism. The buildings on our block were a mix of brick, turn-of-the-century, four-flat worker houses and single-family homes, most owned by absentee slumlords. On our block alone lingered the blackened shells of five burned-out buildings. As in most poor areas, the locals were highly transient, their average residency being about six months. Families moved in, quickly fell behind on their rent, and slipped away under the cover of darkness, on to the next rental unit.

Before I moved in, my wife had tried various means to improve the quality of life of our block. She and a neighbor started a block newsletter, but this died after an issue or two due to lack of interest. She attended neighborhood association meetings, but these meetings proved more frustrating than helpful.

Among the many things I had to get used to when I moved in with my wife to our home on Pennsylvania Ave. were the frequent eruptions of gunfire, which often commenced shortly after dinnertime and continued sporadically until early morning. Our initial response to the gunfire was to call 9-1-1. “Shots fired on the 3600 block of Nebraska” became a familiar echo in our home.

These phone calls were the exception.

A case-hardened social worker with the Department of Family Services, my wife opposed calling police on the neighbors (gunshots, domestic violence proved exceptions), preferring to personally address antisocial behavior. Often she would throw on her clothes and march outside at 2 a.m. and ask a street full of teens or twenty-somethings to turn down their car stereo. I would follow anxiously outside to make sure she was safe, whining that such confrontations were too dangerous. Sometimes the street kids obliged, other times they called her a “white bitch” and told her it was “their street.” The idea seemed to be if we weren’t willing to adapt to their late-night street culture, we should sell our home and move elsewhere. The middle-class suburbs, perhaps. That option was pretty much a non-starter. Even if we wanted to, selling the house could take years, and, besides, there were other residents on the street, who, like us, had to get up early for work, but were too afraid to confront the noisemakers. We were speaking for these people, too. The silent minority.

My wife’s personal touch would even extend to drug dealers. Without warning, she would sometimes walk past an SUV in which a drug deal was obviously going down and shout “Not on our street!”, no doubt startling buyer and seller with her brashness. Again I begged her to refrain. It all seemed like an excellent way to get a bullet in the face.

Our block slowly became more livable once the midnight street parties moved indoors or to other streets. But drug dealing continued to be a major problem. Even if you called the cops, as the various “How to Rid your Street of Drug Dealers” stories advised, the drug deal was often wrapped up, the participants long gone, by time the cops arrived.

The stories also warned that getting rid of dealers was about an easy as getting rid of cockroaches in a New York City apartment. It was going to take some strategic thinking. It would require serious risks. But after a year of living on Pennsylvania and witnessing my wife’s example, I was ready to take some risks. And I had a plan.

I had read somewhere about the Broken Windows Theory of policing, and it sounded tailor-made for our situation. The theory, in short, held that disorder and crime go hand in hand, so you begin by tackling the disorder. So if a city, a neighborhood, perhaps even one resident on a block, adopted zero tolerance for small crimes — like kids smoking weed in front of their apartment building, a common enough occurrence on our block — the effect would be a reduction in more serious crimes, like drug peddling. Practically speaking, if word got out on the block that “someone” was calling the cops over every little joint, every open container, the drug pushers would find more hospitable streets. It seemed worth a try.

My wife gave her blessing. It was settled. From then on, whenever I saw one of my neighbors or their friends using drugs — even smoking weed — on their stoop or in their car I would immediately call the cops.

***

One of our neighbors, a young African-American kid in his late teens or early twenties, spent most days and nights hanging out on his stoop smoking weed with his buddies. We’d warned him about getting high on his grandfather’s stoop. His reply, in effect, was that it was his yard, so he could do what he pleased. We (somewhat lamely) explained that what he was doing was a crime and it sent a signal to drug dealers that such crimes, and illegal drugs in particular, were tolerated on our street. He shook his head and laughed.

So the next time I noticed him smoking weed outside I called the cops. I felt guilty about it, and a little frightened, but at that point there was no going back. It was the drug dealers or us — and this kid was seemingly on the side of the drug dealers. Three cruisers responded immediately, all flashing gumballs and blu-whup siren blasts. You’d think someone had just shot the governor. Naturally the kid was safely indoors when the cops arrived. Only his senile grandfather remained out front, staring unseeingly at the cops.

The next afternoon the kid confronted me in my front yard, asked why I called the cops. I repeated my lame sermon about the message public drug use sent, feeling like the nerdiest hipster ever.

He just shook his head and muttered something about getting even with me.

About this time a local musician and his wife and infant daughter moved into the abandoned house next door. They had purchased the house for $15,000 and spent a few months thoroughly rehabbing the place. On nearby Cherokee Street they opened a whiskey bar. We quickly became friends. Cherokee Street was fast becoming a hipster hub, and it wouldn’t be long – we hoped — before more artists and musicians and alternative shop owners moved into the neighborhood, perhaps creating a nice mix of artists and, well, normal poor people.

Indie music artists, though, are known to smoke a little weed from time to time. You could see my dilemma. Suppose the new neighbors took to smoking weed on their deck?

“Ask them not to,” my wife said. Then, presumably, if they continued, I’d have to call the cops. Anything short of that would peg me as a phony, unethical, racist bastard. Pretty much the worst scum on Earth.

Fortunately it never came up. The neighbors didn’t do drugs. Not that I noticed, anyway.

But still. It forced me to reevaluate the whole Broken Windows strategy.

And there was more reevaluating to come.

There was no denying the quality of life improved on our street. Yes, the trash still piled up in the yards and on the sidewalks and curbs and gutters. There was still occasional gunfire, burglaries, drug deals, but they were less frequent. The street and back alley were relatively calm at night. It might simply have been that the new neighbors who circulated in and out were better behaved, or had fewer teenage children. It might have been that more and more houses got boarded up so there were fewer renters. Or, yes, it could have been our strict willingness to call the cops over small, quality-of-life crimes.

But at what cost?

Broken Windows Theory, everyone agrees, sounds great on paper, but often left out of the equation are the unintended consequences.

As numerous commentators pointed out after the 2014 death of Eric Garner, who died of a heart attack while being brutally arrested for selling single cigarettes on a Staten Island street: “broken windows leads to broken heads.”

Or worse.

Some law enforcement experts say constant stops for minor violations — quality-of-life crimes — tend to make those arrested flip out in a way more serious crimes do not. Not surprisingly the constant indignities cause some to lose their temper. That’s because stops for bullshit ordinance violations feel like harassment. These detainments feel unjustifiable in a way a stop for a serious crime doesn’t. And, in fact, they often are unjustifiable. It’s these confrontations that often escalate dramatically into more serious situations, such as resisting arrest or felony assault of a peace officer.

***

Recently we left the inner city and moved to the St. Louis suburbs to be near my wife’s family. Actually just a few blocks from Ferguson, Missouri, where Broken Windows was very much in the news at the time.

In Ferguson, the cops were notorious for their hot-spot policing of the few poor, minority neighborhoods and for profiling black drivers. It’s a familiar story. The white kid with the baggie of coke in his jacket is stopped in one of the area’s notorious speed traps, but let go without a search. A black driver, who is 66 times more likely to be stopped in North St. Louis County, is similarly pulled over, but his vehicle is searched and – jackpot! – a joint is found. The white driver goes home. The black driver goes to jail. It was this daily form of harassment that led to the profound discontent and feeling of disrespect that underpinned the recent protests. I found myself agreeing with the Ferguson protesters over black residents’ unequal treatment by the cops.

Thus, I found myself questioning Broken Windows.

Had we been wrong to adopt this zero-tolerance policy toward petty crimes? Had our actions only served to anger an already embittered underclass, just so we could go to the work in the morning without falling asleep at our desks? Were we contributing to the problem of low-level African-American drug offenders getting locked up in our nation’s overcrowded prisons? Would we have called the cops on our hipster neighbor friends if they were getting stoned on their back porch? Could our frequent calls to police have led to the next Michael Brown or Eric Garner-like incident?

My wife, who is far more broad-minded than I, reminded me that our anti-crime efforts did seem to get the drug dealers off our street. And that was the main thing.

It is a reminder that actions often have both good and bad consequences and that there are no easy, pat solutions to the age-old problems of race, crime and economics, and anyone who thinks there are is fooling himself.