"Serial" is one of those projects I’ve admired from a distance, catching up on episodes in my spare time while cowering at the prospect of the amount of thought I’d have to put into it to match the erudition of its most obsessive fans.

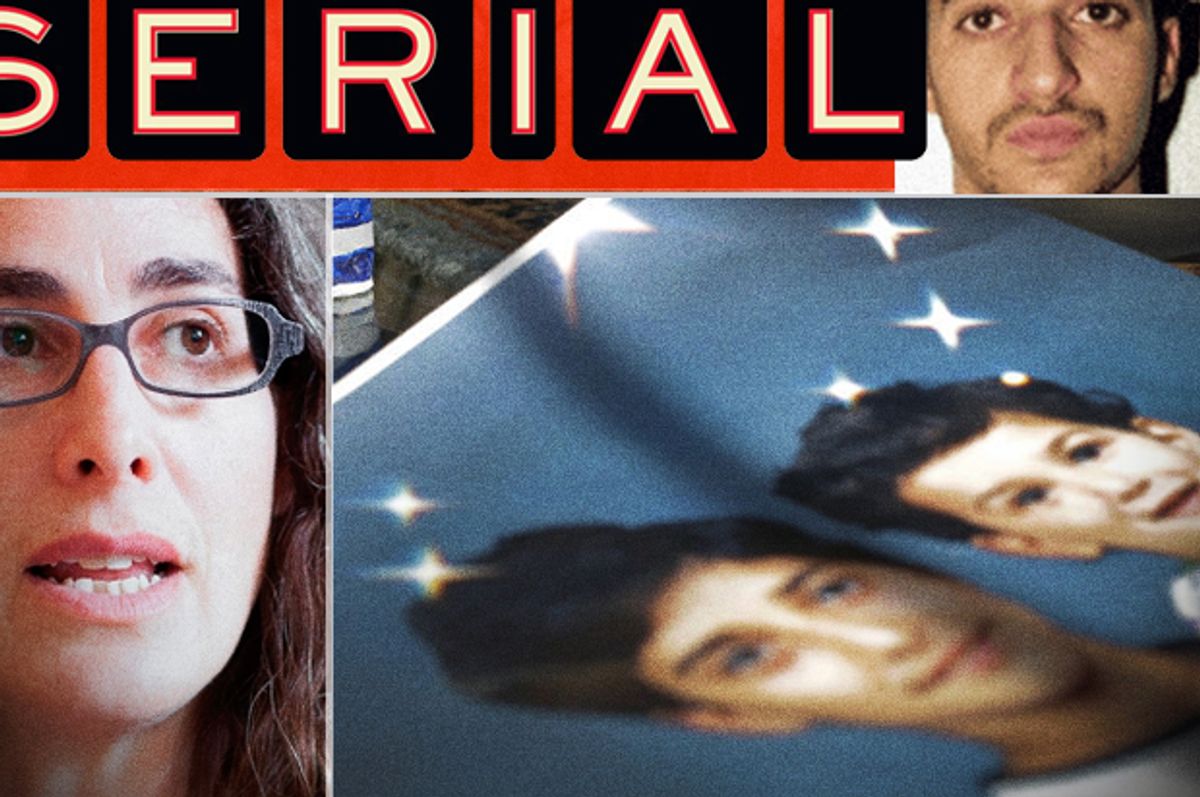

I’m fascinated if only because it’s so weird that a journalist doing a radio story about a 15-year-old cold case--the alleged murder of high school senior Hae-Min Lee by ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed—has become the headline-making news that it has. Other people, much more invested than I am in the story, have done reams of analysis--both analysis of the crime that forms the central plot of the story, and analysis of the problems with the ways the story has been told--that I can’t hope to match.

But here’s what struck me about "Serial," as we hit the closing chapter of one of the most unlikely media success stories of our age:

The cold case in "Serial" is not, as cold cases go, particularly complex. It’s particularly shocking because it involves the worst possible crime, a murder, but compared to, say, your average investigation into financial misconduct at a mid-size company, the case is simplicity itself.

The crime is clearly defined (nobody disagrees on the definition of murder or that Hae-Min Lee was murdered). The number of actors is small--even if you cast the widest possible net the number of people involved is fewer than 10. The question of fact is highly limited in scope--can Adnan Syed account for his whereabouts in the two hours from 2:30 to 4:30 p.m. on Jan. 13, 1999?

And yet even this relatively simple question has produced reams and reams of speculation. An extremely active subreddit with people throwing theories, claims, counterclaims at each other nearly constantly. Long analytical think pieces from very smart people calling other very smart people gullible fools.

And this is something that happened only 15 years ago, in the modern era, in a world of email and mobile phones. Even after an exhaustive investigation that went far deeper than the police did and being self-admittedly “obsessed” with this case, Sarah Koenig can’t even construct one consistent timeline for the rest of the day minus those problematic missing two hours, much less make a definitive statement of what Syed was doing in those two hours.

No witness’ story actually aligns with the story told by any other witness. The two people at the center of this case--Syed and his accuser, Jay--contradict themselves repeatedly when asked to account for the events of that day.

People have said that we’re so much more connected today, that if this murder happened in 2014 rather than in 1999 it’d be solved very quickly. Imagine if Hae-Min Lee had a Twitter account and we could read her last few tweets from before she died. Imagine if Adnan Syed had had a smartphone with an active GPS that could be tracked. Imagine if we could use the MAC address of Adnan’s smartphone to see if it’d automatically logged in to the public library’s Wi-Fi network when Asia McClain said she saw him there.

But information derived from technology is never that unambiguous, as Koenig’s struggles with cell tower tracking reveals. As someone who’s seen friends creepily stalked by amateur Internet sleuths, I can testify to people’s ability to “put pieces together” to get amazingly incorrect results based on evidence they think is unshakable, sometimes with tragic results. When I try to track my own movements for the past few days through my Twitter feed I find that I’m not able to do so, because a combination of discretion and laziness means my feed isn’t actually a very accurate reflection of my moment-to-moment activity at all. And even if someone were able to pull my GPS data, my phone (which admittedly has been through an unusual degree of abuse) as of this morning still somehow thought I was in Manhattan.

Some fans have criticized the 12th and final episode of "Serial" for anticlimax, showing a critical lack of self-awareness in doing so. (If Koenig had found miraculous evidence exonerating Syed, do you think Syed would’ve patiently waited in prison for Koenig to finish her podcast?)

Indeed, if "Serial" were a work of fiction, Koenig would be coming under tons of fire for cheating the audience--for not even having an ambiguous ending that hinges on a single defining question forcing us to choose between two possible narratives, but having no ending at all and no clear narrative of what actually happened regardless of whom you believe.

And that’s the reality of the world: Stories don’t usually add up. Every narrative has inconvenient evidence that appears to contradict it--every single one, including the completely true ones. It’s not that eyewitness testimonies and memories can be “distorted” by bias, it’s that every recollection of memory is basically our brains making up stories we tell to ourselves to explain the few scraps of information we actually perceive.

That’s the lesson of Kurosawa’s "Rashomon," to which "Serial" has often been compared, which imitators of the “Rashomon Plot” tend to forget--in real life, no omniscient narrator gives you the “real” story afterward.

It’s that feeling of just not knowing that we, as viewers who demand “resolution” in stories, are uncomfortable with. And therein lies the problem.

As I alluded to up top the extremely uncomfortable thing about "Serial" is hearing people discuss horrible things that happened to real people--a young woman dead, a young man imprisoned, families and communities torn apart--as though they’d been made up by Vince Gilligan or Matthew Weiner for their entertainment. (Hae-Min Lee’s brother made this exact complaint about the podcast on Reddit.)

It deeply sucks to get your dirty laundry trawled through by strangers on the Internet. It sucks to have people look at a photo of you and decide that you seem “sociopathic” or not based solely on your face (something that I have some personal familiarity with).

It sucks to have your words dissected by amateur lawyers who think everyone needs to hear their opinion, like the people who decided they didn’t like me and should therefore look into whether I should go to prison for admitting in an interview once that I’d known people I was pretty sure were guilty of sexual assault but didn’t report it to the cops.

So I’m familiar with how much that kind of thing sucks, even if on a much smaller level than when it’s a case of murder. And I’m troubled by how quickly in this day and age Internet-based scrutiny crosses the line into dangerous intrusive actions in the real world, like when a Redditor tracked down Jay and drove by his house--and Koenig ended up doing the same thing (which she admitted was a “dick move”) and confronting Jay without his consent to an interview.

But you know what’s suckier than all of those things? It sucks that they’re necessary. If nothing else, "Serial" should destroy any blind faith you may have held that the U.S. justice system “gets it right.”

Whether you think Syed is guilty or not, nearly everyone who’s watched Koenig’s investigation agrees that it revealed a deeply screwed-up trial with a huge number of improprieties by police and prosecution and a badly botched defense. And there’s no particular reason to think this case is unique.

Yes, the outrage machine of social media is a dangerous tiger to ride. But if not for that outrage machine, the deaths of Mike Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice--the stories that are now dominating our headlines and our conversations--would likely have gone ignored by a legal system deeply biased in favor of law enforcement and a media that, bluntly, generally doesn’t seem to think of the deaths of young black men as “news.”

Look at the other big news story this year that won’t go away, prominent celebrities accused of sexual assault and rape. Look at the sheer volume of accusations, and the quickness with which people seize on “inconsistencies” and “contradictions” in the stories of accusers in order to dismiss them. Look at the UVA case right now, where we got the same massive volume of contradicting anecdotes, claims and counterclaims in a few days that Koenig generated after a year of reporting.

The inconvenient thing about murder is it leaves a corpse, an obvious glaring piece of evidence that makes it impossible to walk away.

If not for the “outrage machine,” the legal system would’ve probably kept on doing what it typically does with issues of police brutality, with issues of “he-said-she-said” rape accusations against powerful men and with difficult cases in general--ignoring them.

It may well be that, despite all the problems with the trial, the jury got the right answer anyway and Syed is guilty of murdering Lee. It may well be that the worst detractors of the Rolling Stone UVA story are right and that no sexual assault of any kind happened to “Jackie” and her account was completely falsified (unlikely as that seems).

None of that means it was wrong for the questions to be asked. As uncomfortable and upset as "Serial’s" breakout success has made Lee’s family, the Syed family has been clear that despite how unlikely it is Adnan Syed will ever be released from prison, the simple fact that someone is asking the questions that were never asked is bringing them closure; it “brought [them] all back together."

I try to take everything I hear with several grains of salt. To her credit, Koenig does too throughout the run of "Serial," including questioning her own “obsession” with this one case and whether she’s giving it too much weight simply because “it’s the one that landed in my lap.” But the big lesson in "Serial" should be that just because the authorities didn’t ask a question doesn’t mean the question wasn’t worth asking. Just because the authorities think something is settled doesn’t mean it is. And people who keep banging the drum of “Go to the authorities! It’s irresponsible to take these things to the public!” (like, say, Aaron Sorkin) need to rethink what they're saying.

It’s easy to see why people want “going to the authorities” to be a final, ultimate answer, why people put so much weight on verdicts obtained in court. We want to be able to walk away feeling that the issue has been resolved and the world restored to rights. But of course there is no “right answer”--if you take the message of “beyond a reasonable doubt” as it’s meant to be taken, you understand that the world is filled with wrongs that can’t and won’t ever be proven in a court of law but still really did happen. That when two exes after a breakup both accuse the other one of being the “abusive, crazy” one you’ll probably never be able to piece together “the truth” by playing detective on Facebook and Twitter no matter how hard you try. That when someone confides in you that they were sexually assaulted by someone they dated but they’ll never be able to prove it to the cops, the chances are pretty good that they’re right.

And that you’ll always have to live your life with that same doubt that Koenig says she has to live with, when looking into Adnan Syed’s big brown eyes--that the world is filled with ambiguity and that you will never be able to prove whether the people you hang out with might or might not be horrible people and you may just have to live with the doubt that they might be. That’s a far, far darker message than Hollywood usually gives us--even "True Detective" catches the bad guy at the end. But it's one we have to live with.

Shares