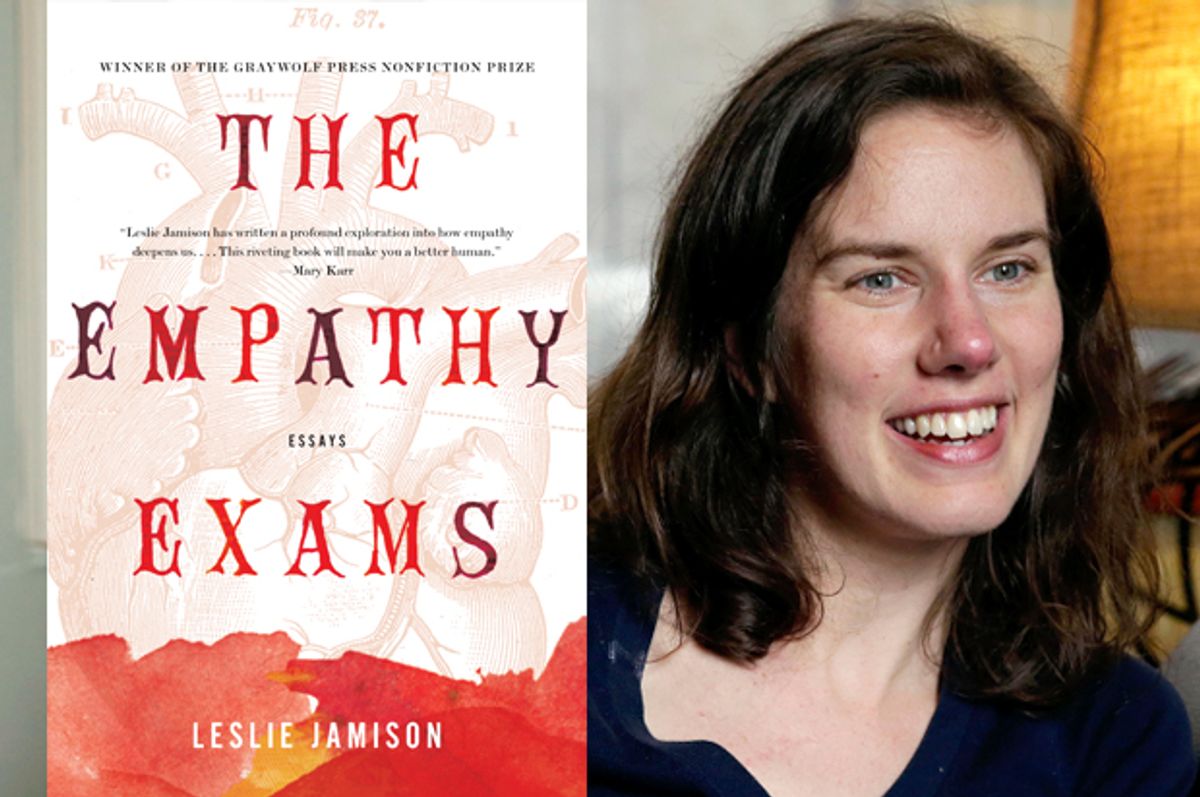

Leslie Jamison's "The Empathy Exams" came out from Graywolf Press to much acclaim, and people bought and read and discussed her brilliant essay collection with such rare gusto that it landed on the New York Times best-seller list. She has a remarkable ability to take other people’s stories alongside her own and present necessary narratives that stay with the reader long after finishing the book.

As part of Salon's series of year-end conversations with some of the most essential nonfiction voices of 2014, we spoke both over the phone and then by email about everything from Ebola to selfies to tattoos.

Your collection is in so many ways about pain, about how we face and discuss and experience illness and pain. So I'm curious about a story that broke after your book was published: How do you think our country is handling Ebola victims and the medical workers who have traveled overseas?

I was doing an event in Chicago a few days after Craig Spencer was diagnosed with Ebola — after returning from his work for Doctors Without Borders -- and all of New York was going crazy and the Internet was publishing maps of where he’d gone bowling in Williamsburg and where he’d eaten a snack and which subway lines he’d ridden. Somebody asked me whether I felt like Americans were showing enough empathy about Ebola. It was something I’d already thought about in relation to the uproar over Spencer -- how sometimes fear can be the enemy of empathy.

If this man were going through something similar in a faraway place -- i.e., he’d been doing important medical work and had gotten diagnosed with a potentially fatal illness -- people might have respected his bravery. But in this case, many people’s primary reactions had to do with their own proximity to danger. It was striking to me how that sense of fear -- a kind of communal panic -- seemed to trump feeling empathy for him, much less respecting him for the choices he’d made. One of the things we need to push back against in order to access feelings of empathy and understanding can be various kinds of self-concern, fear being one of those.

That said, to be totally honest and tell on myself, I was also checking which subway lines he’d been riding: had I ridden those lines? I know I’m not immune from the infectious quality of communal fear. I also think our response to Ebola illuminates something abiding and unfortunate — that we have a harder time caring about suffering when it’s far away.

There was an outpouring of outrage and pain over the events, and grand jury decisions, in Ferguson and here in New York City with Eric Garner. What’s the role of the writer when it comes to documenting these critically important stories of social injustice?

I think Ferguson is a really important illumination of the different roles that individuals and collective groups can play in responding to social injustice. There’s something absolutely amazing to me about the breadth and depth and expansiveness of the collective action that’s happening in response to Ferguson. Almost every day in New York, I feel like I’ve been in contact with some sort of march. But the police are out a lot more too. I walk by certain corners and they are just six policemen deep. There’s a sense of menace in that heightened presence. But I do think that there’s a power and an articulation that happens with a sheer number of bodies on the street, speaking out.

That’s the kind of work that no single writer can do, because it depends on having that many bodies and that kind of collectivity. But it’s also been a real solace to me to have writers I respect -- Roxane Gay is coming to mind — offering commentary and reactions to what’s been going on, how we might think about these high-profile events in relation to our everyday lives. "Citizen," by Claudia Rankine, was also a really important book for me this year in helping me think through how racial tensions and injustice show up everywhere — not just headline news but ways that are less visible, easier to ignore. So what is the role of the writer in relation to these events? To offer a voice questioning the way that things are being handled. To offer a voice calling attention to the ways people have suffered and the ways that they’re still suffering. The work of the writer has always been about making the invisible visible.

On a much lighter and more personal note: I’m interested in your thoughts on selfies, especially because you write about the body in such vivid detail in some of your essays and so much of your book incorporates other people’s stories alongside your own. The selfie in a lot of ways is kind of akin to a personal essay. Is there room for self-examination in a non-narcissistic way without bringing oneself into the context of the larger world?

The idea of being able to represent yourself in a photograph rather than being represented by somebody else; I think there’s a whole realm of possibility in that. And I don’t think there’s anything intrinsically narcissistic or self-involved in the idea of self-representation. It’s like the Internet — I’m not for it or against it. The question is: How can it be used in an interesting way? When I see selfies that seem directed toward commodifying the self as a sex object or something like that, it’s less that I feel like they are self-involved and narcissistic and more that they seem like missed opportunities. It seems like certain societal expectations or pressures are just being regurgitated by somebody who has internalized those pressures so much that they’re representing themselves through their lens. But I think selfies get interesting when people do them in surprising ways, or use them to surprising effect -- make you feel like you’re sharing a private moment with somebody even though you’re not there and you know it’s an illusion — that it’s a private moment. It’s artifice and access at once. That’s where the selfie can be a really cool thing.

Definitely. If you could change one thing about the literary world, what would it be?

I would want the literary world to curate more actively the voices of people who don’t have power or money or access to literary prestige. How can we create an environment where these stories are heard? It’s not an easy question to answer, but it’s an important imperative. Some examples come to mind; there are plenty more out there: I mentor for the PEN Prison Writing program, which pairs up incarcerated writers with mentors who work with them by correspondence. This poet named Mark Nowak did a program with NYC taxi drivers where he had them write their own stories and then hosted a reading. So I think there are all kinds of means by which we can try to create a space for hearing voices that don’t usually get heard. It brings to mind questions about equal representation in media, and disparities in how voices get compensated. Julia Wong has written some powerful and provocative pieces for The Nation about people of color in media, and how voices on Twitter can get appropriated for other peoples’ stories.

But thinking about making access for voices from various margins — that’s certainly where my mind goes when I think about how I’d want the literary world to be different: What stories are getting told, and what stories should be getting told, and who should we be listening to, and who aren’t we listening to.

You’ve participated in a lot of conversations and panels this year while on your book tour. What have you learned from engaging with other writers in front of a live audience?

That’s a great question. One thing I’ll say is with my first book I did a lot of solo events. It was a very pointed decision this time around: I wanted to do events with other people. There are a couple of reasons for that, but one is that I love the idea of a non-repeatable event. If you have a particular combination of minds or voices, it’s going to create something that’s never happened before and isn’t going to happen again. I like that.

For example, when I read in Ann Arbor, I read with my friend V.V. Ganeshananthan, who is writing a novel about a former Tamil Tiger. The portion she read for our event was about political action and violence and thinking about the ways that bodies hold scars, and how these scars hold meaning. So her ideas were intersecting my ideas about empathy from an entirely different direction: fiction rather than nonfiction; the implications of political violence. The people in the audience got a chance to hold two very different perspectives in mind; feel them chiming off each other.

A lot of the events that I loved most this year have been rewarding partially because they’ve happened outside the boundaries of the literary community. I’ve spoken to medical school communities. I spoke to a group of outpatient mental health caregivers — social workers and therapists -- in Connecticut, people who work with clients who don’t have anywhere else to turn. I spoke at a psychiatric hospital in Princeton a couple weeks ago. And at those events, the kinds of questions and reactions I get from the audience are coming from a totally different angle than writers’ questions would. It’s not about how does formal experimentation work in these essays; it’s about how empathy might be effective in a clinical setting. I don’t necessarily feel like an expert, but I can offer a perspective from beyond the bounds of their discipline; and they offer that to me as well.

You got a tattoo with the epigraph to your book that says “I am human. Nothing human is alien to me.” And you wrote a wonderful essay for the New York Times in which you talked about the reasons for getting that tattooed, mostly freedom from an ex. But you’ve had quite the year, first with the success of your book and then with meeting, falling in love with and marrying the writer Charles Bock. I’m wondering if looking at this tattoo now, does it hold an even deeper meaning for you than it did when you first got it?

Certainly, certainly. That tattoo has always related to the end of that relationship and also a lot of other things. It now holds the experience of the book going out into the world -- feeling the different ways people have responded, this idea of resonance in a more general sense. What are the possibilities of resonance? What are its limits? What are the dangers of assuming too much resonance or trying to pretend that we can understand each other more than we actually can? One thing I like about the tattoo is it holds my memories of people who resisted it, or didn’t agree with it, or wanted to question it. Most recently, a warden in a Kentucky prison. He said something to the effect of: Nothing is alien to you? I’m not so sure about that.

And Charles and I first started talking because he asked me about the tattoo — what it meant. So now it holds the memory of our first meeting, too, and everything that came after.

So I feel like so much of what we read on the Internet is about immediate gratification. Writers post a short blog post to get their thoughts out into the world. Facebook status updates stand in as mini-essays. But we’ve also seen some commitment to long-form works this year, like Jill Abramson announcing her new venture to pay writers and websites like The Atavist that published your essay. What’s the biggest challenge for writers in this state of information overload?

I do think that writers face certain perils in the Internet era that have to do with the ease of publishing and the possibility of publishing things without working on them for a long time. And so much great writing happens because it marinates for a long time. Emily Cook has this great essay in The New Inquiry about how first reactions or early reactions aren’t necessarily more authentic. Sometimes we have a tendency to associate immediacy with authenticity, but often the most authentic thought or narrative is one that’s been considered and reconsidered and worked over. That practice of working on pieces for a long time -- holding on to them for a long time and revising them over a long period of time and coming back to them over and over again — I don’t think we should let go of that. And I don’t think that digital culture means we have to let go of that, but I think it can function as a Siren. I feel it too. We have to plug our eyes and tie ourselves to the mast. It’s a perilous kind of affirmation: the possibility of immediate publication and the gratification of immediate readership.

Jason Diamond and Tobias Carroll wrote great think pieces about this being the year of the essay. Do you agree? I know we spoke about this at length in a previous interview for Salon, but what changes have you seen in the way that essays are read and discussed?

I'm glad that this is being touted as "the year of the essay" -- and certainly glad to see work by writers I admire (Charles D'Ambrosio, Meghan Daum, Roxane Gay) getting wonderful attention and circulation -- but it also strikes me as somewhat humorous. The essay has a long history and it’s such a basic form -- not "basic" in the sense of easy, but "basic" in the sense of primal: a transcription of a mind reckoning with some subject -- what could possibly be more compelling or intuitive? Why hasn't every year been the year of the essay? I do think that the capaciousness of the essay -- in particular, its ability to simultaneously hold personal material and outward inquiries (critical or journalistic) -- is part of its appeal right now; it can offer the intimacy of access alongside the wider horizon of exploration beyond the self.

Who are some of the great thinkers (writers, painters, architects, etc.) that influenced or inspired you this year?

I can tell you about a few of the artists who have really gotten deep under my skin this year, although there are too many to list. I read Chris Kraus's “I Love Dick” for the first time and it floored me: the way it negotiates the dynamics of exposure, plays with obsession as an empowering rather than degrading force, talks openly about how female desire is perceived and received… it felt like running into the snow from a hot tub, that crazy tingling of my own nerve endings activated. I've been a Maggie Nelson fan for a while, but I got to revisit both “The Art of Cruelty” and “Bluets” for a criticism seminar I was teaching at the NYU Journalism School -- a bunch of deeply thoughtful, truly talented aspiring critics whose bylines I'll be watching out for in the years to come -- and I was so moved, once more, by how Nelson treats her own interior life with rigor, and treats the rigors of criticism with a sensitivity forged deep in her interior life.

Two art exhibitions really electrified me this year: Wangechi Mutu at the Brooklyn Museum -- especially her work with the female body and consumption: a video of herself squatting in front of a chocolate cake, stuffing fistfuls in her mouth, is one of the most powerful transcriptions of the fraught female relationship to consumption I've ever seen. I watched it multiple times; just stood there transfixed. I also loved a Lucio Fontana exhibit I saw at the Musee d'Art Moderne in Paris over the summer. He's known for making holes in his work -- neat slits, sweeping gashes and ragged mouths -- and I was captivated by the effect: this idea of puncturing the stillness of a single color, or a single material -- some finite canvas in the foreground -- to suggest the infinite beyond. "Who knows how God is?" he said. "So I made holes." That says something about my process of writing essays, as well.

Shares