Director Ava DuVernay says she knew back in December that she wouldn’t be the first African American woman nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director for “Selma,” which is up for the Best Picture award. In a story published yesterday, Entertainment Weekly reports the director chalked it up to simple Academy math, and it turns out she might be right. The Academy is overwhelmingly white (94 percent) and male (77 percent). While we might want to think of artistic awards as strictly merit-based, race and gender may very well have worked against DuVernay—several Academy voters indicated to EW that DuVernay’s unequivocal response to criticisms of her portrayal of President Lyndon Johnson as reluctant on civil rights “came off as strident and defensive.” In a majority culture that can paint outspoken African American artists with the “angry black woman” brush, and that only just awarded a woman the best director statue in 2009 (Kathryn Bigelow for “The Hurt Locker”), a lack of representation allows one side to dominate the conversation and dismisses what they don’t want to hear.

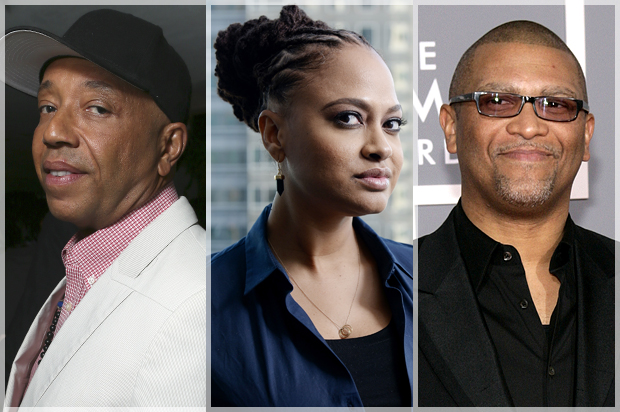

The conversation would be different if an African American woman helming a Best Picture nominee wasn’t already such a rare occurrence. In a new interview with Variety, venerable hip-hop (and now film and TV with his Def Pictures) producer Russell Simmons criticized Hollywood’s “deafening” lack of racial integration: “The segregation in Hollywood is incredible.” He also blasted well-meaning Hollywood liberals who see themselves as more progressive than they are when it comes to understanding African-American culture and how that cultural blindness can stifle minority talent from rising to the tops of their fields.

That attitude shines through in the Entertainment Weekly story on DuVernay, where one Academy member defended their decision: “It’s almost like because she is African-American, we should have made her one of the nominees. I think that’s racist. Look at what we did last year with ’12 Years’.”

There it is—the attitude that if the Academy fêted a film about slavery one year, it absolves itself of having to pay close attention to artists of color the next. Reginald Hudlin, one of the producers of 2013 Best Picture nominee “Django Unchained,” wondered about what he called “the unknowable question” about “Selma” in an essay for The Hollywood Reporter: “whether the same voters who supported ‘12 Years a Slave’ had racial fatigue after supporting a black film last year.” But Hudlin also says that this only highlights the bigger problem: “It’s easier for a black person to become president of the United States than it is to be president of a movie studio.”

“Selma” is up for Best Picture with only a Best Original Song nomination to back it up, while films that have won Best Picture since the Academy expanded the list to include up to ten nominees have also received nominations (and wins, even) for categories that, it would seem, contribute heavily to a film’s Best Picture contender status—directing, acting, writing, art direction, cinematography, costume design, editing, sound design.

A Best Picture can certainly forego a directing nominee—Ben Affleck’s “Argo,” for example—but the dearth of nominations across the board for “Selma” raises questions that do, indeed, seem unknowable. What makes a “best picture” if the acting, directing, writing, design and storytelling aren’t also stellar, or if the film isn’t among the year’s most beautiful or meticulously executed? Even “Argo” garnered seven nominations, including best adapted screenplay, which it won. It’s clear from its Best Picture nod that in general, the well-meaning, progressive, overwhelmingly-white members of the Academy recognize on some level that “Selma” is a noteworthy film, but the lack of further accolades indicate that they may not understand, or be willing to entertain so quickly on the heels of “12 Years a Slave,” what—and who—makes it so.