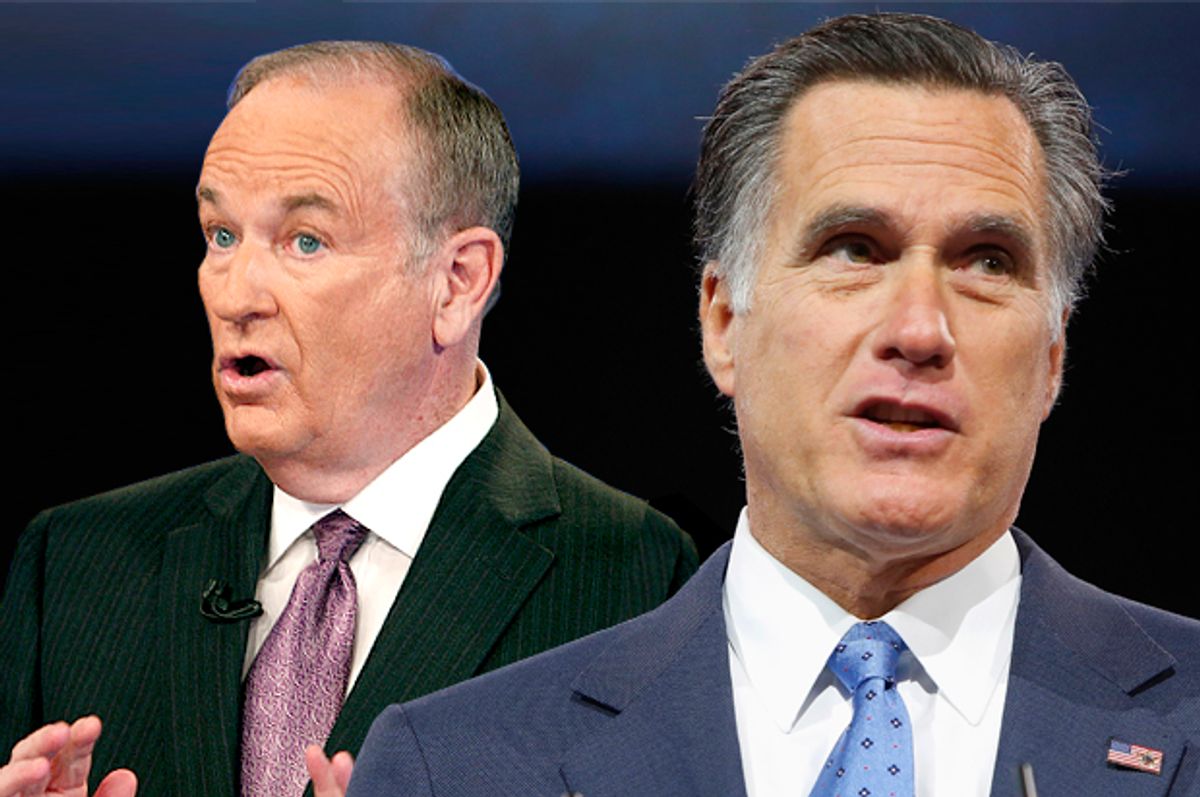

Mitt Romney got religion, when it comes to helping the poor. And wasn't alone among Republicans of late—a sure sign that Elizabeth Warren-style populism is far more popular than most in Washington want to admit— so his departure as a presidential hopeful won't put an end to the GOP's new wave of psuedo concern.

But he is the most unlikely example, so it helps to clarify just what that meant, before the endless oceans of campaign spending muddle it beyond recognition. First and foremost, he explains himself, it's a matter of perception. Reporting on a Coachella Valley event Romney did the day before Obama's State of the Union, Fox News noted:

The 2012 Republican nominee said one of the lessons he learned from that failed effort was the need to communicate to voters “who I am – not just through the policies I talk about but the places that I go and the audiences I speak to.”

Romney specifically identified a desire to personally address minority communities and younger audiences. “If you show up at businesses it looks like you’re a business person. If you show up at churches and at minority communities it shows you care much more broadly. And that’s something that I want to do.”

So, look like you care about the 47 percent! Got it! What could be simpler? No wonder Mitt thought he was ready to run again. He had found his silver bullet, what else did he need? Remember no-show weekend flyboy George W. Bush pretending to be an actual combat pilot? The press just ate that one up. Why shouldn't they be just as gullible with Romney?

The press was not his problem, as it turned out. It was Republicans themselves. They were not going to make things easy for him. But two more things Romney did rounded out the picture. First, he pulled back from his over-the-top opening bid, but affirmed that conservatism already provided all the answers:

Romney did not repeat his call to “end the scourge of poverty” but rather breaking what he called the cycle of poverty. “The reason that I am a Republican is because I believe the principles of conservatism are the best to help people get out of poverty and the best to help people have opportunity and rising wages.”

That's an utter fantasy, of course. Social Security, Medicare and mass industrial unionization were three of the most powerful anti-poverty measures of the 20th century, and conservatives bitterly opposed all three. What's more, research using the newly developed alternative supplemental poverty measure now clearly shows that government policies starting during the War on Poverty have also had a profound impact. A December 2013 research paper that I cited in a 50th anniversary retrospective story reported that from 1967 to 2011, “without taxes and other government programs, poverty would have been roughly flat at 27-29 percent, while with government benefits poverty has fallen from 26 percent to 16 percent--a 40 percent reduction.” So, 44 years of economic growth has only raised the market poverty rate modestly, but the War on Poverty and the programs built on it, which conservatives have also staunchly opposed, have also been a significant success in fighting poverty.

But the second thing Romney did was reveal that, apparently, he thinks he knows better:

Romney twice cited a Brookings Institution study showing a high school graduate who marries before parenthood and at some point in time holds a full time job is unlikely to live in poverty. He says government policies over the past 50 years have failed to lift America’s poor and that it should focus on policies that will tackle the educational, social and economical benchmarks noted by the Brookings study.

Although Fox News didn't say (and neither did Romney, apparently), it appears that Romney was referring to the same Brookings study that Rick Santorum misleadingly cited in 2012, when he was pretending to be the champion of the poor and downtrodden.

While conservatives, and even some in the media, like to misrepresent Brookings as “left leaning,” it's more centrist than anything else, having been led by Republicans at least as often as Democrats. So Romney vaguely citing Brookings to make his case can be seen as yet another example of his new poverty optics—while also pretending to care about facts, with their well-known liberal bias.

But if any surviving GOP candidates—or anybody else—really wants to go beyond optics and take a good hard look at what really works to fight poverty, then there's a much better place to go looking for research papers—the Luxembourg Income Study, housed at the LIS Data Center, which has data from dozens of advanced industrial nations dating back to the 1960s, as well as more than 600 working papers based on their data.

Almost all the poverty research done in America is focused on America, a shortsighted perspective that severely limits our understanding and neglects most of what's been proven to work to fight poverty internationally. Hence, even the most “liberal” results coming out of this research tradition tend to be shortsighted and limited. This U.S.-centric tradition of analysis is “is inherently parochial, for it is based on the experiences of only one nation,” as noted in LIS working paper number 244, “United States Poverty in a Cross-National Context,” by Timothy Smeeding, Lee Rainwater and Gary Burtles.

To get some sense of how unusual the U.S. is, consider this quote: “The per capita income of the United States is more than 30 percent higher than it is, on average, in the other ten countries of our survey. Yet the absolute poverty rate in the United States is 13.6 percent, while the average rate in the other 10 countries is just 8.1 percent—5.5 percentage points lower than the United States rate.” So, 30 percent higher average incomes, but 68 percent higher poverty rate. Clearly economic growth alone won't do much to lower poverty significantly. U.S. poverty is even more exceptional using a relative poverty measure, which is a more accurate reflection of how people experience their lives and judge others as well. American child poverty is particularly problematic and exceptional, as we'll see below.

The problem of American parochialism is not just a matter of focusing on a too-small realm of data, but also of neglecting different sorts of analytical perspectives and policy approaches, which have proven track records elsewhere but are largely ignored here, not just by the political class, but in some ways and cases even by researchers as well. As a result, entering the world of the LIS working papers is a bit like waking up from a dream. Things you thought were real, solid and very well understood turn out to be quite insubstantial, while other things you had no idea of while dreaming now appear as solid as concrete. Indeed, the world revealed by the LIS data is as far removed from Republican economics as the world revealed by climate science data is removed from Republican climate denial. The chief difference is that, when it comes to poverty policy, Democrats are only marginally more in touch with the larger reality than Republicans are.

To begin with, the LIS data leave no doubt at all about America's outlier status, which pops up again and again in various LIS papers, but is made particularly clear by two charts in Smeeding's LIS Working Paper No. 419, “Poor People in Rich Nations: The United States in Comparative Perspective.” Figure 1 is titled "Relationship of Cash Social Expenditures and Non-Elderly Poverty Rates in Eleven Industrialized Countries circa 2000." It shows the U.S. in the upper left corner with a 16 percent poverty rate and a social expenditure (cash and near cash) of about 4.0 percent of GDP. Finland, Belgium, Sweden and the Netherlands fall on the opposite side of the chart, with poverty rates from 4 to 8 percent and social expenditures of about 11 to 15 percent of GDP. Six other countries lie in between.

That's not the whole story, of course. Figure 2 is titled "Relationship of Low Pay and Non-Elderly Poverty Rates in Eleven Industrialized Countries circa 2000." It finds the U.S. in the upper left corner, again with a poverty rate of 16 percent and more than 25 percent of full-time workers earning less than 65 percent of median earnings. Finland, Sweden and Belgium are in the opposite corner, with poverty rates from 4 to 6 percent, and just slightly more than 5 percent of workers earning less than 65 percent of median earnings. So, in short, the U.S. has both the most low-income workers and the smallest welfare state for helping those in need.

In that same paper, Smeeding also found that the U.S. was a dramatic failure in reducing poverty for families with children compared to other countries. The 11-nation average for reducing market-income poverty was about 45 percent, for both single-parent and two-parent families, but the U.S. did far worse in both categories—a 10 percent reduction for single-parent families, and a minuscule 3.6 percent reduction for two-parent families. These results are so shockingly bad that they bear closer scrutiny, so we can understand just how far we fall behind what other nations do for the least fortunate among them—remember, these are all families with children we are talking about.

The U.S. started off near average in its poverty rate for single-parent families in terms of market income—46 percent compared to a 50 percent average, but it fell behind when social insurance (universal programs, like Social Security) and taxes were added to the mix, 48.1 percent to 39.5 percent, and even further behind when social assistance (targeted programs, like food stamps) was added as well, 41.4 percent to 26.5 percent. While total social spending and taxes reduced the single-parent poverty rate by just 10 percent in America, the reduction averaged 46.3 for all 11 countries combined—more than four and a half times better than us. Clearly, there's something here we can learn from others. How much of an outlier was the U.S.? The next least vigorous nation in fighing poverty was Italy, with a 22.4 percent reduction, more than twice that of the U.S. The most vigorous, Finland, reduced poverty eight times as much as we did—80.8 percent.

We like to think that the problem of poverty is simply a matter of single-parent families—as reflected in Romney's remarks—but it's not. As already noted, America does even worse at fighting poverty for two-parent families. Again, we started off with a market poverty rate close to the average: 13.7 percent to 13.3 percent, but with social insurance and taxes included our poverty rate went up, while the average went down: 15.2 percent to 9.8 percent. Add in social assistance and we start to do better, but the gap persists: 13.2 percent to 7.6 percent. Italy is the only country with a higher poverty rate in the end, though four countries started out with higher market poverty rates. Our total poverty reduction by government was just 3.6 percent, compared to a 44.3 percent average—so we did much worse at reducing two-parent poverty than single-parent poverty. The average poverty reduction was more than 12 times more than ours. The next lowest nation was Italy, again, but at 11.7 percent it did more than three times better than we did. The most vigorous improvement came from Sweden, which reduced poverty 76.6 percent for two-parent families (more than 20 times better than us), for a final rate of just 2.2 percent.

That paper provides an excellent snapshot of where the U.S. stands compared to other countries, and it's not pretty. American exceptionalism is quite real—but not in the way we'd like to think. Other LIS working papers add more details that can help us see more clearly the sorts of things we need to do if we're really serious about fighting poverty here in what's still the wealthiest nation on earth.

Consider the question of how to fight child poverty, which underlies the abysmal figures cited above. We can learn a great deal from LIS working paper 558, “Policies to Reduce Child Poverty: Child Allowances Versus Tax Exemptions for Children,” by Steven Pressman. According to the website's summary, “It finds that a $3,000-$4,000 child allowance would reduce child poverty in the US to the level of other developed nations and, due to the costs associated with child poverty, be a cost effective policy change.” In the U.S., conservatives claim that tax credits and tax exemptions are the answer to everything. But Pressman noted, “They reduce child poverty by only 0.7 of a percentage point, well below the poverty‐reducing impact of child allowances for all other countries in our tables. This is not surprising given that poor households with children pay very little in taxes.” Indeed, child allowances pack roughly 10 times the whallop. “On average (including the U.S.), they reduce child poverty by close to 7 percentage points, but there are large differences across nations due to the generosity of national family allowance programs,” he wrote.

The reason why child allowances are so much better is obvious: They “are an upside-down subsidy, giving greater support to those households that need less help providing for their children. They are the equivalent of bailing out large financial institutions about to fail, but not supporting average homeowners struggling to make mortgage payments,” Pressman explained. With a $4,000 child allowance, our child poverty rate would fall to 14.8 percent, cutting it almost in half, and putting it around the average of all the nations studied. That would cost $160 billion, but Pressman cites a 2007 research paper by Harry Holzer of Georgetown, and three co-authors, which placed the costs of U.S. childhood poverty at about $500 billion per year, almost 4 percent of GDP, including lost productivity and increased crime and health care costs as primary factors. Taking these costs into account, America would actually come out ahead by spending that money on its children.

Raising children is first and foremost the responsibility of parents, and we naturally tend to think of everything else as secondary to that, which in one sense it most certainly is. But much of what parents do is cope with circumstances beyond their control, and Holzer's analysis highlights the fact that individual children are part of much larger patterns of cause and effect, like great storms on the sea of life, which their parents can only partially protect against. The role of social scientists and policymakers is (or at least should be) to study and come up with ways of protecting against those storms in ways that are practically effective. The LIS working papers have much to teach us—some of it quite surprising—about what's effective and what isn't.

Another paper that provides a big-picture look at this challenge is LIS Working Paper #407 “Structural Theory and Relative Poverty in Rich Western Democracies, 1969-2000,” by David Brady. The paper compares three types of explanation for poverty—structural factors (“manufacturing employment, agricultural employment, female labor-force participation, the elderly population, and children in single-mother families), economic performance (three measures: economic growth, productivity, and unemployment rate) and the impact of the welfare state (two measures: Social security transfers as a percent of GDP, and public health spending as a percent of total health spending). He uses two key measures of poverty, a headcount of how many are poor, and an intensity (or interval) measure, multiplying the headcount by the depth of poverty. He describes his findings in a number of ways, but the bottom line is strikingly clear:

For the headcount, the structural variables have a more powerful influence than economic growth (the only significant indicator of economic performance) but a smaller influence than the welfare state. For the interval measure, the welfare state has a much larger influence than economic growth, and the insignificant structural and other economic variables.

So, economic growth, which all American politicians agree on as the cure for poverty, has the least impact, while the welfare state, which even staunch Democrats get defensive about, has the largest impact. Such is the level of disconnect between reality and the American politics of poverty, which, Brady concludes, is crucial: “[T]he welfare state is fundamentally a political outcome. As a result, poverty is a political outcome as well.”

The demonization of single mothers, and poor people more generally as “takers” is, of course, one of the most salient factors in keeping America's welfare state so small compared to other countries'. Racism and other forms of social stereotyping have obviously been implicated as well. Not all such factors can be fruitfully studied internationally via datasets like the LIS, but considerable light can be brought to bear, nonetheless, particularly from other papers Brady has co-authored.

For example, LIS working paper 554, “Targeting, Universalism and Single Mother Poverty: A Multi-level Analysis Across 18 Affluent Democracies,” by Rebekah Burroway and David Brady, shows that targeted policies—tailored specifically for those who meet narrow criteria, as America's welfare programs have always been—are remarkably ineffective, in contrast to universal social policies, which provide a powerful antidote to single-mother poverty.

The study uses two measures of welfare state universalism. The first, Welfare State Index, combines the two measures described in the previous paper. The second, Universal Replacement Rate, is an average (not targeted) measure—“the average percent of median income that typical residents of a country receive from the state.” While there's a wealth of information discussed along the way, the main finding is clearly stated:

Our central conclusion is that generous, comprehensive and universal welfare states substantially reduce the poverty of single mothers.... If the U.S. increased its welfare state index to the mean or to Sweden’s level, the odds of single mother poverty would decline by a factor of 3.8 or 13.3. If the U.S. increased its universal replacement rate to those levels, the odds of single mother poverty would decline by a factor of 4.5 or 17.9. As noted above, these effect sizes are large in comparison to the individual-level variables. Although policy and demographic debates often focus on altering the behavior or characteristics of single mothers (e.g., encouraging education, employment, fewer children and marriage), welfare universalism could be an even more effective anti-poverty strategy.

Since poverty involving single mothers is the single most prominent focus of attention in American politics, and child poverty is largely a function of parental poverty, it makes sense to complement this view with a look at overall working-age poverty. Another LIS working paper does just that: number 487, also co-authored by David Brady, “Putting Poverty in Political Context: A Multi-Level Analysis of Working-Aged Poverty Across 18 Affluent Democracies.” The topline results are quite similar to single-mother poverty:

For each standard deviation increase in welfare generosity, the odds of poverty decline by a factor of 2.3. The odds of poverty in the U.S. (the least generous welfare state) are greater by a factor of 16.6 than a person with identical characteristics in Denmark (the most generous welfare state). If the U.S. had even the mean level of welfare generosity (-.391), the odds of poverty for the average person would decline by a factor of 2.94.

Beyond that, however, this paper goes on to show that welfare state generosity is a result of political effort:

We show that Leftist [labor or socialist] parties and union density reduce the odds of poverty, however their effects channel through the welfare state. Ultimately, poverty is shaped both by individual characteristics and the political context in which that individual resides.

In particular, the paper notes:

If the U.S. had either average or the highest level of union density (i.e. Sweden, see Table 2), the odds of poverty would decline by a factor of either 1.61 or 4.65.

If the U.S. had average Leftist party power or the highest level (i.e. Sweden, see Table 2) [rather than a score of zero], the odds of poverty would decline by a factor of 2.25 or 12.96.

Not all of the impact of leftist parties and unions is channeled through the welfare state, but that which is not did not reach the level of statistical significance.

An obvious spin-off question from the above paper is what happens when unions are weakened, as they have been in recent years, particularly in the U.S. Brady and two co-authors tackled this question in LIS working paper 590, “When Unionization Disappears: State-Level Unionization and Working Poverty in the U.S.” Not surprisingly, that paper found:

Across all models, state-level unionization is robustly significantly negative for working poverty. [Poverty goes down as unionization goes up.] The effects of unionization are larger than the effects of states’ economic performance and social policies. Further, unionization reduces working poverty for both unionized and non-union households and does not appear to discourage employment.

So, the union-busting of Scott Walker, which has made him such a conservative darling, is a sure-fire way of increasing poverty—what a surprise! While it's popular in America to claim that unions drive up wages for their members at the expense of other workers, the extensive cross-national data in the LIS firmly refutes this claim. The paper also notes how odd it is that the working poor are so commonly neglected:

While the unemployed poor averaged only 3.4 percent of the U.S. population from 1974 to 2004, the working poor averaged 10.4 percent. Despite its prevalence, working poverty has been neglected compared to the voluminous literature on joblessness.

One obvious reason for neglecting the working poor is that it's much harder to demonize someone who's working hard day to day, but still living in poverty. They're doing exactly what the jobless poor are told to do, but they're still living in poverty. Their very existence calls into question the whole logic by which the jobless poor are demonized, so it's simply more convenient to ignore their existence—and even most of the research literature falls into line with the mainstream bipartisan politics on this score.

There's much, much more to be found in the hundreds of LIS working papers, but what's summarized above should be more than enough to show how far out of touch we Americans are when it comes to seriously reducing poverty. Mitt Romney is anything but alone on that score—he's just a teeny bit more blatant than most of the rest of us, that's all. The perfect leader for a country in denial. But, since he's made the ultimate sacrifice, and decided not run, maybe the rest of us can give up our denial as well, and finally consider some truly proven poverty-fighting measures. Oh, sure you can say that they're foreign, European, socialist, whatever. Or you can say that they're pragmatic—and there's nothing more American than that.

Shares