There are lots of good physiological reasons why people find heads fascinating, and powerful, and tempting to remove. The human head is a biological powerhouse and a visual delight. It accommodates four of our five senses: sight, smell, hearing and taste all take place in the head. It encases the brain, the core of our nervous system. It draws in the air we breathe and delivers the words we speak. As the evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman has written, ‘Almost every particle entering your body, either to nourish you or to provide information about the world, enters via your head, and almost every activity involves something going on in your head.’

A huge number of different components are packed into our heads. The human head contains more than 20 bones, up to 32 teeth, a large brain, of course, and several sensory organs, as well as dozens of muscles, and numerous glands, nerves, veins, arteries and ligaments. They are all tightly configured and intensely integrated within a small space. And people’s heads look good too. The human head boasts one of the most expressive set of muscles known to life. It is adorned with various features that lend themselves to ornamentation: hair, ears, nose and lips. Thanks to an impressive concentration of nerve endings and an unrivalled ability for expressive movement, our heads connect our inner selves to the outer world more intensely than any other part of our body.

This extraordinary engine room – distinctive, dynamic and densely packed – is set on high for all to see. Our bipedal posture means that we show off our relatively round, short and wide heads on top of slim, almost vertical necks. The necks of most other animals are broader, more squat and more muscular, because they have to hold the head out in front of the body, in a forward position. The human head, because it sits on top of the spinal column, requires less musculature at the back of the neck. There is so little muscle in our necks that you can quite easily feel the main blood vessels, the lymph nodes and the vertebrae through the skin. In short, it is much easier to decapitate a human than a deer, or a lion, or any of the other animals that are more usually associated with hunting trophies.

Which is not to say that it is easy. Human necks may be, compared to other mammals, quite flimsy, but separating heads from bodies is still hard to do. Countless stories of botched beheadings on the scaffold attest to this, particularly in countries like Britain, where beheadings were relatively rare and executioners were inexperienced. The swift decapitation of a living person requires a powerful, accurate action, and a sharp, heavy blade. No wonder the severed head is the ultimate warrior’s trophy. Even when the assassin is experienced and his victim is bound, it can take many blows to cut off a person’s head. When the Comte de Lally knelt, still and blindfolded, for his execution in France in 1766, the executioner’s axe failed to sever his head. He toppled forward and had to be repositioned, and even then it took four or five blows to decapitate him. It famously took three strikes to sever the head of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1587. The first hit the back of her head, while the second left a small sinew which had to be sawn through with the axe blade. It was hard even when the victim was dead. When Oliver Cromwell’s corpse was decapitated at Tyburn, it took the axeman eight blows to cut through the layers of cerecloth that wrapped his body and finish the job.

For all its unpredictability, when it is skillfully performed on a compliant victim, beheading is a quick way to go, although it is impossible to be sure how quick since no one has retained consciousness long enough to provide an answer. Some experts think consciousness is lost within two seconds due to the rapid loss of blood pressure in the brain. Others suggest that consciousness evaporates as the brain uses up all the available oxygen in the blood, which probably takes around seven seconds in humans, and seven seconds is seven seconds too long if you are a recently severed head. Decapitation may be one of the least torturous ways to die, but nonetheless it is thought to be painful. Many scientists believe that, however swiftly it is performed, decapitation must cause acute pain for a second or two.

Decapitation in one single motion draws its cultural power from its sheer velocity, and the force of the physical feat challenges that elusive moment of death, because death is presented as instantaneous even though beheadings are still largely inscrutable to science. The historian Daniel Arasse has described how the guillotine, which transformed beheading into a model of efficiency, ‘sets before our eyes the invisibility of death at the very instant of its occurrence, exact and indistinguishable’. It is surprisingly easy to forget, when contemplating the mysteries of death, that decapitation is anything but invisible. Beheading is an extremely bloody business, which is one of the reasons it is no longer used for state executions in the West, even though it is one of the most humane techniques available. Decapitation is faster and more predictable than death by hanging, lethal injection, electric shock or gassing, but the spectacle is too grim for our sensibilities.

Decapitation is a contradiction in terms because it is both brutal and effective. A beheading is a vicious and defiant act of savagery, and while there may be good biological reasons why people’s heads make an attractive prize, a beheading draws part of its power from our inability to turn away. Even in a democratic, urbanized society, there will always be people who want to watch the show. Similarly, severed heads themselves often bring people together, galvanizing them in intensely emotional situations, rather than – or as well as – repelling them. Decapitation is the ultimate tyranny; but it is also an act of creation, because, for all its cruelty, it produces an extraordinarily potent artefact that compels our attention whether we like it or not.

Even the relationship between the perpetrator and the victim can bring surprises, because there is sometimes a strange intimacy to the interaction, occasionally laced with humour, as well as sheer brutality. Each different encounter with a severed head – whether it be in the context of warfare, crime, medicine or religion – can change our understanding of the act itself. People have developed countless ways to justify the fearsome appeal of the severed head. The power that it exerts over the living may well be universal. For all their gruesome nature, severed heads are also inspirational: they move people to study, to pray, to joke, to write and to draw, to turn away or to look a little closer, and to reflect on the limits of their humanity. The irresistible nature of the severed head may be easily exploited, but it is also dangerous to ignore. This book tells a shocking story, but it is our story nonetheless.

*

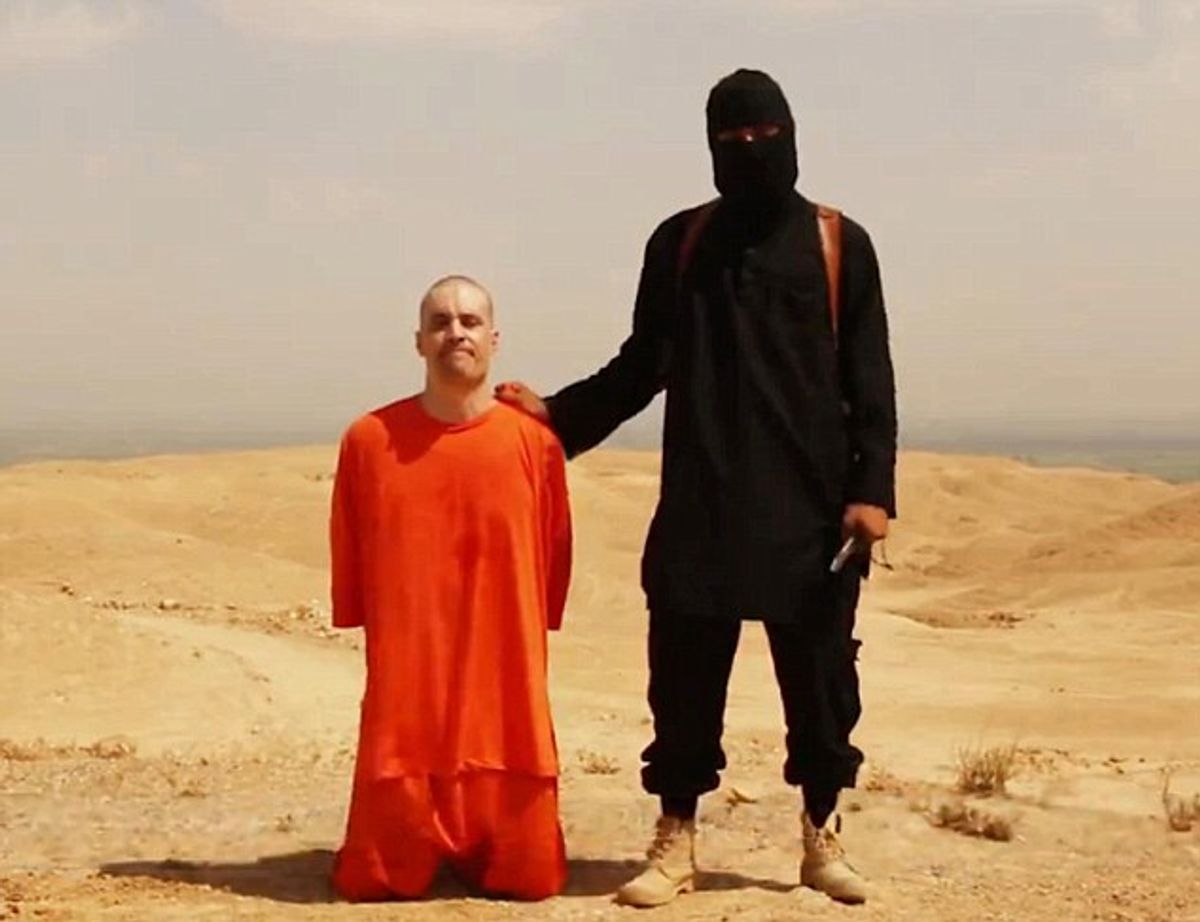

The scaffold is the ultimate stage, where, for centuries, life and death were acted out for real. In the mid-eighteenth century, Edmund Burke observed that theatregoers enjoying a royal tragedy would have raced to the exit at the news that a head of state was about to be executed in a nearby public square. Our fascination with real misfortune, he pointed out, is far more compelling than our interest in hardships that are merely staged. He might have said the same today, but in the digital age, the internet mediates our view of grisly executions, simultaneously keeping us at a distance and giving us front-row seats. Today, severed heads are held up for the camera and the spectators can watch at home. During the Iraq War, the extraordinary allure of beheading videos was proved for the first time, and in no uncertain terms.

As the American and British ‘war on terror’ moved across Afghanistan and into Iraq in the years following the September 11th terrorist attacks, a new mode of killing took the media by surprise: Europeans and Americans were taken hostage by Islamic militant groups, held for ransom and then beheaded, on camera. Throughout history, criminals have been decapitated for their crimes; now, the criminals were decapitating civilians in terrifying circumstances, and graphic videos of their deaths were circulated online for anyone to see.

The first American victim was Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, who was kidnapped in Pakistan in January 2002. His captors demanded the release of Taliban fighters in Afghanistan, in what was to become a typically unrealistic ultimatum. They beheaded Pearl on 1 February. A few weeks later the video of Pearl’s death emerged. It started to circulate online in March, and in June the Boston Phoenix newspaper provided a link to it from their website, a move which proved extremely unpopular with commentators in the United States who scorned the paper’s ‘callous disregard for human decency’, but the Boston Phoenix site nonetheless spawned a wave of further links to the video, and discussions about the rights and wrongs of viewing Pearl’s brutal death proliferated online.

The second American to be killed in this way, and the first to be beheaded in Iraq, was Nick Berg, an engineer who was kidnapped on 9 April 2004 and killed in early May. This time, two years after Pearl’s death, Reuters made the unedited video available within days, arguing that it was not within its remit to make editorial decisions on behalf of its clients. In contrast to the video of Pearl’s execution, which was only shown on CBS as a thirty-second clip, all the major US television news networks showed clips of the Berg video, although they stopped short of actually broadcasting the beheading itself. The traditional news media refrained from showing the footage in full, but by now television producers were following the crowd rather than breaking the story; it was internet users who, in the privacy of their own homes, dared to watch Berg’s beheading.

Nick Berg’s execution video quickly became one of the most searched-for items on the web. The al-Qaeda-linked site that first posted the video was closed down by the Malaysian company that hosted it two days after Berg’s execution because of the overwhelming traffic to the site. Alfred Lim, senior officer of the company, said it had been closed down ‘because it had attracted a sudden surge of massive traffic that is taking up too much bandwidth and causing inconvenience to our other clients’. Within a day, the Berg video was the top search term across search engines like Google, Lycos and Yahoo. On 13 May, the top ten search terms in the United States were:

nick berg video

nick berg

berg beheading

beheading video

nick berg beheading video

nick berg beheading

berg video

berg beheading video

‘nick berg’

video nick berg

The Berg beheading footage remained the most popular internet search in the United States for a week, and the second most popular throughout the month of May, runner up only to ‘American Idol.’

Berg’s death triggered a spate of similar beheadings, by a number of militant Islamic groups in Iraq, that were filmed and circulated online. There were 64 documented beheadings in Iraq in 2004, seventeen of the victims were foreigners, and 28 decapitations were filmed. The following year there were five videotaped beheadings in Iraq, and the numbers have dwindled since. In 2004, those that received the most press attention proved particularly popular with the public. In June, an American helicopter engineer, Paul Johnson, was kidnapped and beheaded on camera in Saudi Arabia, and in the weeks after his death the most popular search term on Google was ‘Paul Johnson’. When the British engineer Kenneth Bigley was kidnapped in Iraq in September 2004 and beheaded by his captors the following month, one American organization reported that the video of his death had been downloaded from its site more than one million times. A Dutch web-site owner said that his daily viewing numbers rose from 300,000 to 750,000 when a beheading in Iraq was shown.

High school teachers in Texas, California and Washington were placed on administrative leave for showing Nick Berg’s beheading to their pupils in class. When the Dallas Morning News printed a still image of one of Berg’s assailants holding his severed head, with his face blocked out, it said that its decision had been inspired by interest generated in the blogosphere. The paper’s editorial pointed out that ‘[o]ur letters page today is filled with nothing but Berg-related letters, most of them demanding that the DMN show more photos of the Berg execution. Not one of the 87 letters we received on the topic yesterday called for these images not to be printed.’

It is, of course, impossible to know how many people actually watched the videos after downloading them, but a significant number of Americans wanted to see them and discuss them, particularly the video of Berg, who was the first American to be beheaded in Iraq, and whose execution was the first to be recorded on camera since Pearl’s, two years earlier. Berg was killed just as public support for the war in Iraq was beginning to decline, and the popularity of the video underlined the extent to which the internet had eclipsed more traditional news media when it came to creating a story. Television news producers may have edited their clips of the video, but it did not matter because people were watching the footage online. The internet allowed people to protest against the perceived ‘censorship’ of the mainstream media, or else simply circumvent the media altogether when the mood took them. Whether people thought it ‘important’ to see Berg’s execution for themselves, or simply watched out of curiosity, there can be little doubt that ‘the crowd’ was taking control, or was out of control, depending on your perspective.

One survey, conducted five months after Berg’s death, found that between May and June, 30 million people, or 24 per cent of all adult internet users in the United States, had seen images from the war in Iraq that were deemed too gruesome and graphic to be shown on television. This was a particularly turbulent time during the war that saw not only Berg’s beheading, but also the release of photographs showing the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib by American military personnel, and images showing the mutilated bodies of four American contract workers who had been killed by insurgents in Fallujah, dragged through the streets and hung from a bridge over the Euphrates. Nonetheless, Americans were seeking these images out: 28 per cent of those who had seen graphic content online actively went looking for it. The survey found that half of those who had seen graphic content thought they had made a ‘good decision’ by watching.

The decision to view Berg’s beheading became politicized online. Bloggers claimed it was no coincidence that the liberal news media dwelt on the harrowing images from Abu Ghraib, which undermined the Bush administration’s credibility in Iraq, while – as they saw it – sidestepping the Berg story by giving it fewer column inches and refusing to show the full extent of the atrocity. ‘One day the media was telling us we had to see the pictures from Abu Ghraib so we could understand the horrors of war,’ Evan Malony wrote. ‘But with Berg’s beheading, we’re told we can’t handle the truth . . . The media that had – rightfully, in my opinion – showed us the ugly reality of Abu Ghraib prison refused to do the same with Berg’s murder.’ Professor Jay Rosen was more explicit: ‘They aren’t showing us everything: the knife, the throat, the screams, the struggle, and the head held up for the camera. But the sickening photos from Abu Ghraib keep showing up.’

Other viewers admitted to watching execution videos simply out of curiosity, with no ‘higher’ purpose. One anonymous internet user said, ‘You almost can’t believe that a group of people could be so pitiless as to carry out something so cruel and bestial, and you need to have it confirmed . . . Watching them evokes a mixture of emotions – mainly distress at the obvious fear and suffering of the victim, but also revulsion at the gore, and anger against the perpetrators.’ Meanwhile, website editors expressed a similar range of attitudes towards showing the content. They made the videos available either because they were dedicated to the fight against terror (people should see) or because they were opposed to the ‘censorship’ of the mainstream news media (people should be able to see), while ‘shock sites’ posted the footage purely as macabre entertainment alongside the other violent and provocative videos that drew their clients (watch this!).

Decapitation videos draw viewers who watch unapologetically and viewers who watch despite their own deep misgivings, and the internet offers everyone anonymity. The camera promises spectators a degree of detachment, but the action is only a click away, and this combination gives the videos far greater reach. As the military analyst Ronald Jones put it, with little more than a camcorder and internet access, a militant group can create an ‘international media event . . . that has tremendous strategic impact’. Indeed, as terrorist attacks go, decapitating your victim on camera is an extremely efficient and effective strategy. It requires little money, training, equipment, weaponry or explosives: beyond the initial kidnapping, it does not rely on complicated coordination or technology that might fail, and the results are easy to disseminate. According to Martin Harrow, another analyst, it is a strategy that ‘has maximum visibility, maximum resonance and incites maximum fear’.

No wonder, then, that the Iraq hostage beheadings were ‘made for TV’. Other terrorist activities, like suicide attacks or bombings, are hard to capture on camera because they are necessarily clandestine, unpredictable and frenetic events, but the decapitation of a hostage can be carefully stage-managed, choreographed and rehearsed while still remaining brutally authentic. The footage is clear and close up. The murderers are offering their viewers a front-row seat at their show; and what they want to show is their strength, their organization, their commitment to the cause, their complete control and domination of their victim. When one Italian hostage, a security officer named Fabrizio Quattrocchi, jumped up at the moment he was about to be shot by his captors on film and tried to remove his hood, shouting, ‘Now I’ll show you how an Italian dies!’, Al Jazeera withheld the resulting video because it was ‘too gruesome’. Was this a small victory for Quattrocchi in the face of certain death? No one saw the footage of his murder online, either for entertainment or for education, and his captors could not capitalize on his death in the way that they had planned.

During these carefully staged execution rituals, everyone, even the victim, must play their part. The whole procedure is a piece of theatre designed to create power and cause fear, just as with state executions stretching back to the thirteenth century, except, as John Esposito, a professor at Georgetown University, pointed out, when it comes to executions like Berg’s, ‘it’s not so much the punishing of the individual as the using of the individual’. Even when the victim is an innocent hostage, the power that comes from killing is exerted over a wider community. The crowd is compliant too. By turning up to see the show, or by searching Google for the latest execution video, the people watching also have their part to play.

‘The point of terrorism is to strike fear and cause havoc – and that doesn’t happen unless you have media to support that action and show it to as many people as you can,’ said one analyst interviewed by the Los Angeles Times shortly after Nick Berg’s execution. These murderers post their videos on the internet because they know that the news media will be forced to follow the crowd. Television news programmes either become redundant by refusing to air videos that are freely available online, or else they do exactly what the murderers want and show the footage to a wider audience. Meanwhile, the internet provides a ‘void of accountability’, in the words of Barbie Zelizer, where it is unclear who took the images, who distributed them and who saw them. The whole experience is lost in the crowd.

Adapted from "Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found" by Frances Larson. Copyright © 2014 by Frances Larson. With permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

Shares