Leora Tanenbaum is not a slut. That didn't stop her from being labeled as such during her years in school, nor did it stop her from being bullied for her sexuality -- just like countless other young women across the country. As a result of her own "slut-bashing," a term she coined in her first book, "Slut! Growing Up Female With a Bad Reputation," Tanenbaum decided to dedicate herself to researching the word "slut" and the ways its prolific use harms girls and young women.

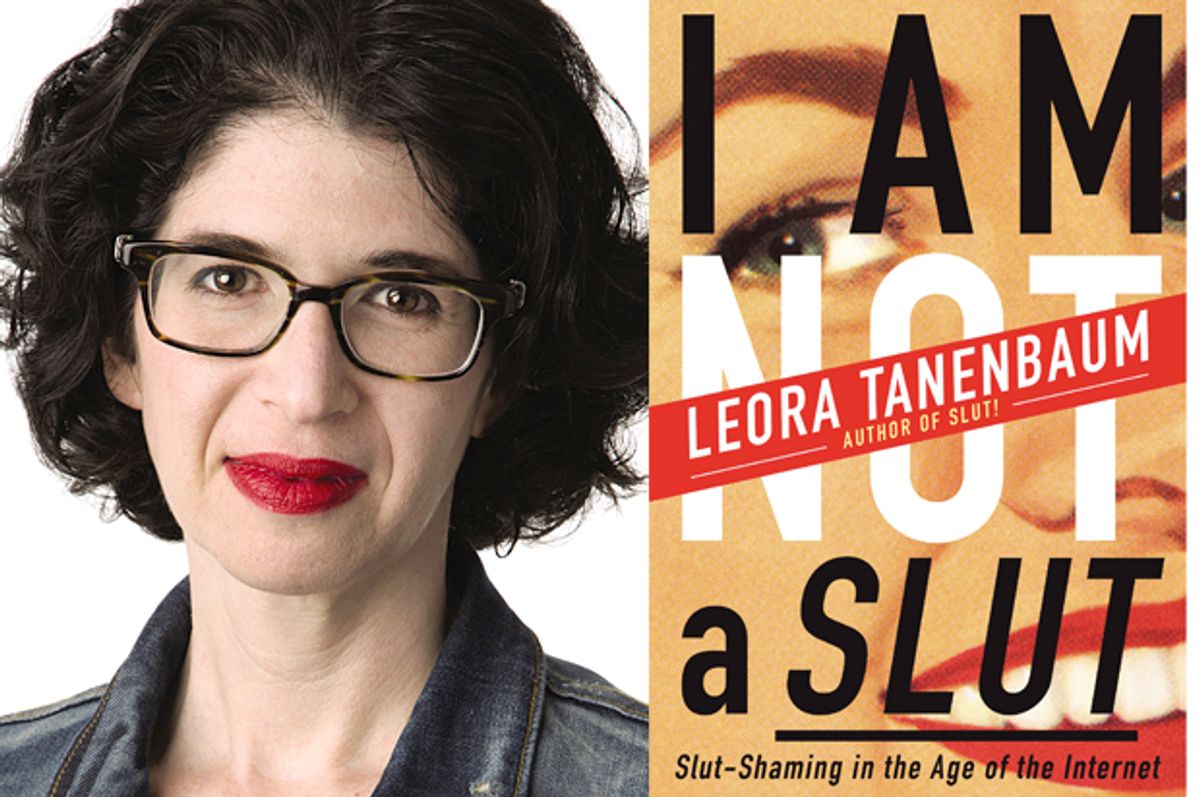

Fifteen years after the release of "Slut!," Tanenbaum's second book -- "I Am Not a Slut: Slut-Shaming in the Age of the Internet" -- follows the rise of online slut-shaming and the methods by which virtually all young women have been labeled sluts on social media. The book, which came out last week, relies on individual women's narratives to illustrate the pervasiveness of gendered bullying online -- and how Tanenbaum thinks it can be stopped.

It's a multilayered project, which the author -- who also works for Planned Parenthood's communications department -- believes can be accomplished through advocacy online and off. Her employer, she says, offers a good example of what the fight against slut stigma looks like in the real world. "I genuinely believe that what Planned Parenthood does best, which is providing comprehensive sex education and abortion without judgment and birth control without interference from bosses and politicians, is so important for chipping away at slut-shaming," Tanenbaum told me when we spoke by phone last Tuesday. "Because what that does is destigmatize female sexuality, and that means that we are chipping away at a sexual double standard, this whole idea that boys will be boys and girls will be sluts."

Salon spoke with Tanenbaum about her book, the dangers of slut-bashing and why it shouldn't be a priority to reclaim the term. Our interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

I want to start with a question about how you define terms in the book. The title is “I Am Not a Slut” -- so what does it even mean to be a slut, especially as a young girl?

So the word “slut” and its synonyms like “ho” are remarkably confusing, which is why you’re asking the question and which is why these words have so much power, because they really can mean whatever you want them to mean. But nevertheless, in the United States today, I think most of us can agree that the predominant meaning is a negative one, and that by and large it does mean a girl or a woman who is out of control sexually and who therefore deserves to be shamed. There are efforts to rehabilitate the term, and I absolutely recognize that the word in some contexts can be positive and even empowering. But because of the predominant mind-set that unfortunately rules in our culture right now, which is that of the sexual double standard -- the idea that boys will be boys and girls will be sluts -- it’s the negative meaning that really envelopes all the other meanings and really eclipses them.

I know you don’t advocate for reclaiming the term on a macro level or as a form of feminist activism. I conflate it in my mind with how feminism itself, the word “feminism,” has such a bad reputation, and how it is such an important project to try to flip that understanding on its head in the public consciousness. So why not do that with a term like “slut”? Why not make that same effort to own it and turn it around?

Yes, we can come up with examples of words that have been flipped successfully and I’m not denying that at all. But from the evidence that we have so far, this effort is failing -- and I only have to say the words “campus sexual assault” to point in that direction. I am drawing conclusions based on a small-scale journalistic study of 55 girls and women, but we see what’s going on in the culture at large. The bottom line is we do not have sexual equality. My fear is that a large scale embrace of the word “slut” could backfire on us and make us more unsafe than we already are. So my critique isn’t an ideological one at all, it’s a strategic one. Ideologically, yeah, I would love to flip it around and embrace it.

I was talking with my colleague this morning about how effective it is as an activist strategy to rely on individual narratives, as your book does. I wonder if you have any concerns about people not really piecing these individual stories together to create a cohesive illustration of the fact that there’s an institutional problem here -- a double standard, a mistreatment of women. Do you worry that people are going to overlook the fact that all of these narratives construct one larger image of a big, big problem, or that they’re going to respond only to the 55 component parts?

I totally hear what you’re saying. The number is arbitrary, and let’s say for the sake of argument I had collected stories of 500 or 5,000 women. I think somebody that wanted to make that argument would make that argument anyway. I think the individual voices are important because these are voices that don’t get heard; I am elevating these voices, and I think that is a radical act. When somebody is labeled a “slut” or a “ho,” she is being branded with an identity that other people are placing on her, and once that occurs, very often nobody cares what’s really going on. One critique that I heard a lot after my book “Slut! Growing Up Female With a Bad Reputation” came out in 1999 went like this: “You know, I read your book, and yeah this is really sad and horrible that these girls are treated this way -- that they’re labeled and picked on and harassed and that they turned to alcohol and drugs. But isn’t it a good thing that we have this sexual shaming? Because even though it’s terrible for these particular individual girls, it’s good at large because it sends a message to all the other girls that they shouldn’t be having sex when they’re teenagers, and that will be really good because that will lower the rate of teen pregnancy."

So why do you think that belief persists?

Because there is so much discomfort with female sexuality, really at any age, in particular for teenagers. That goes back to the sexual double standard; nobody’s walking around wringing their hands and losing sleep over teenage male sexuality. But what I found anecdotally, again and again and again, is the voices of girls who were not sexually active at all. Zero. Had no sexual expression whatsoever, who were labeled a “slut” or “ho," and after they were labeled, they then became sexually active. And keep in mind, this is true for older women too, but when you’re in high school you’re still developing emotionally, cognitively, on every level. Figuring out your identity is part of that. When everybody is saying, "You’re a slut, you’re a ho," they start to think, “Oh, all right. I’m a slut, I’m a ho. So if I’m a slut, how am I supposed to behave? Oh, a slut is supposed to have lots of random sex with lots of random guys; OK, I guess that is what I’m supposed to do.”

One of the things you talk about is how trying to conform to the “slut” identity and encountering all the shame that comes with it can also lead girls to have unsafe sex. You mention one story of a girl who’s so terrified of going to a [reproductive] health center for fear of being seen and furthering her reputation as a slut, she just doesn’t use contraception. You also just mentioned that some girls will turn to drugs and alcohol. I wonder if you could elaborate on the other dangerous behaviors slut-shaming can lead to, and maybe also the repercussions for self-esteem of assuming a “slut” identity because it's been ascribed to you.

Over and over again girls were telling me about the self-destructive coping mechanisms they turned to, including drug use and abuse, drinking alcohol excessively. I have the stories in the book, I forget if it’s two or three girls, who developed an eating disorder and were very graphically explaining how that happened. Girls would also lie about their sexual histories [to their doctors]. This actually is something I heard from the college-aged women I spoke with a lot. Actually, I think all of them talked about lying about their number of sexual partners. I hate to use the word “lying” because it implies there’s a maliciousness here, but I would argue that the lying in this case is a completely rational self-protective behavior.

It’s a failure to honestly disclose.

Yeah, exactly. This is true of the bisexual and lesbian women I spoke with too, so it’s really interesting how the sexual double standard can cut in myriad ways. Whether heterosexual or not heterosexual, we’re all raised in a culture with a sexual double standard. But if you have a partner who you have reason to suspect is going to judge you based on your number, then yeah, you are going to selectively disclose. So there’s the issue of lying, there’s also the issue of what "counts" -- if you’re trying to be as restrictive as possible, to keep your number as low as possible, then you are going to discount certain sexual acts as "not really sex."

In the book you talk a lot about where race and class intersect when it comes to the slut label, as far as who could even be a slut historically. I’m curious how the racial implications specifically have changed over time, because one of your primary findings is that in the age of social media, everyone’s a slut. It used to be one or two girls in the school and now it’s everyone. So does that apply racially as well?

The 55 girls and women I spoke with are not a random representative selection of young American women who have been labeled "sluts" and "hos." These are people who wanted to speak with me and wanted to participate and who came to me. Having said that, I actually did not find any noteworthy racial or ethnic difference in the overall narrative arc that I describe about being labeled a "slut" or any of its synonyms. It really cut across racial and ethnic lines. I find that really striking that white women, black women, Latina women, biracial women, Asian women, all told me roughly the same narrative. It does make me think about how although we all live intersectional lives, the way I, with my racial privilege, experienced slut-bashing when I was in high school was obviously different from the way other people who may not have racial privilege experienced their slut-bashing; the fact that the basic narrative is the same really just goes to show you that this is a product of the sexual double standard.

So, this is a book about social media and social culture online in addition to all of these other social issues, and I’m curious: With the pace at which the world moves these days, do you worry about having just written a book about the Internet? How much do you think things are going to change? Do you think this relationship with social media and slut-bashing and slut-shaming is here to stay and that a lot of this research that you did is going to hold for a while?

Definitely girls and women now have these tools to fight back against slut-bashing and slut-shaming. So many of them are doing a really fantastic job. My concern is that some people, many people, might think, “Oh, well because all of these teenagers are calling out acts of slut-bashing and slut-shaming, they seem to have it under control, so we can leave them alone and they’re going to take care of it.” When you are a young person, you often don’t have the savvy and the tools; you may know how to create an amazing video and you may know how to orchestrate an amazing Twitter campaign, but you’re just a kid, and the burden should not be on you to fight back as an individual. You also have to have certain privileges to feel that [fighting back] is something that you’re capable of doing. So many young people either don’t have those privileges or just are not developmentally at the point where they feel they can handle that. Which is why I feel that this is a fight for adults to be fighting and we need to be taking the lead. We need to help them. It’s great for those [young people] who are fighting. But that’s not their burden; that’s our burden and we need to help them along.

Shares