It’s hard to claim that sexiness ever falls out of style, but anyone who judged matters on the basis of cutting-edge popular music in the late 1970s and early 1980s might have speculated that a new puritanism had infected the leading rock bands. Not since the age of the castrati had asexuality risen so high in the charts, and arousal levels sunk so low. Punkers and New Wave stars eschewed romance—David Byrne of Talking Heads summed up the sentiment, announcing in his song “Life During Wartime”: there’s “no time for dancing, or lovey dovey; I ain’t got time for that now.” The romantic flame didn’t burn much brighter in the sythnpop or glam metal bands of the day. When Mötley Crüe released its debut album in 1981, the band members wisely chose the title "Too Fast for Love," and many fans applauded their priorities. The disco scene, in particular, now found itself subject to frequent parody, by everyone from Frank Zappa to Sesame Street, and the erotic clichés of the idiom spurred an angry backlash even among music industry insiders. A San Jose radio host inspired many imitators by playing a few bars of a ‘sexy’ disco hit (“Macho Man,” for example), speeding up the song to squeaky gibberish, then adding the sound of a flushing toilet or a person vomiting—followed by a quick switch to a loud heavy metal track. Other deejays in other cities invented their own anti-disco stunts; the most ambitious may have been Disco Demolition Night at a 1979 Chicago White Sox double-header at Comiskey Park, during which a reported fifty thousand dance records were destroyed in a midfield explosion.

Of course, the music industry continued to release songs about love and sex, and many had airplay success. But increasingly these were attacked or ridiculed by critics and fans. When Rod Stewart released his single “Da Ya Think I’m Sexy?” in 1978, he was hammered by rock purists for selling out. Olivia Newton-John sold two million copies of “Physical,” but many millions more laughed at the cutesy sensuality of her performance. Meanwhile a surprising number of hit pop singles put aside romance in favor of chaste or simply strange subjects, such as Christopher Cross’s paean to “Sailing,” Dolly Parton’s song about the workaday “9 to 5” job, Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust,” Frankie Valli’s “Grease,” or Randy Newman’s “Short People.” In a few years, the AIDS epidemic would cause many to think twice about casual couplings, but even before medical authorities and media identified this situation, a noticeable retreat from intimacy could be heard over the airwaves.

Despite these precedents, sexy music came back with a vengeance over the course of the 1980s, but record labels and performers get little credit for this turnaround. The instigators were technology and consumer decisions on home entertainment. The emergence of the music video and the spread of cable television transformed the love song into a visual genre, and the most successful artists of the decade—Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince, Whitney Houston, and others—took full advantage of the new format. Few were paying attention when MTV started broadcasting music videos in August 1981. Only a quarter of U.S. households had access to cable television at the time, and the concept of filming performances of hit songs was anything but new—Hollywood had done this as far back as the 1920s. But the rapid spread of cable during the 1980s and the increasing focus by the music industry on elaborate video presentation of potential hits combined to transform the relationship between performer and audience. No one back then could have predicted the later rise of YouTube and web-driven viral videos, but the groundwork was laid during the MTV era, when song turned into spectacle, and recording artists put aside their instruments to strut, dance, and shake their way to superstardom.

The love song inevitably changed in response to this upheaval in the music business. Record labels had always favored talent with good looks and sex appeal, but these now turned into paramount attributes. The ability to play an instrument or compose songs no longer mattered quite so much. After the ascendancy of MTV, Paula Abdul could emerge from the ranks of cheerleaders for the Los Angeles Lakers as a hit music star, and the move made perfect sense given the new emphasis on sexiness and cool dance steps. The pop act Milli Vanilli, invited to join Abdul on the Club MTV tour which took video stars on the road, couldn’t even sing their own songs, but they looked good on camera and danced with lots of energy—if they had done a better job of hiding their lip-syncing, which eventually turned them into a music industry joke, they might have continued to enjoy their video-driven stardom.

In truth, even the legit stars needed to rely on outside help as music turned into a multimedia pageant. Michael Jackson, Madonna, and other celebrity performers not only required the support of a filmmaking entourage to mount their dazzling videos, but also delegated composing, arranging, and playing instrumental parts to a degree never seen before in the music business; yet the finished product showed the wisdom of this team-oriented approach. When they appeared in the MTV rotation, these artists exuded the charisma of Hollywood stars, and their every step was choreographed, rehearsed, and polished to perfection. The songs played a part in creating an ambience of romance and eroticism, but now only a modest part in expensive productions that drew on every possible tool to maximize the sex appeal of the star. Some griped that music was turning into a bump- and-grind show—and, in truth, many of the dance moves in the hit videos had originated not with George Balanchine or Martha Graham, but in strip clubs and burlesque shows. Yet the very nature of the medium inescapably required the transformation of the love song into a physical demonstration, and the compact nature of the form, typically of three or four minutes in duration, made a nuanced love story almost impossible to convey. Occasionally an artist would stretch out the form and add a narrative setup to the song-and-dance routine—as did, for example, Michael Jackson in 1982 with his thirteen-minute "Thriller" video, produced with an outlay of a half million dollars—but few musicians had the budget or inclination to tell structured stories. The video format usually required performers to cut to the chase, and in matters of love, this meant less courtship and foreplay, and more thrusting hips and crotch-centered camera shots.

Not all of the songs featured in MTV videos dealt with love and sex, but after casting, choreography, and costuming were completed, even the least romantic tunes, invocations to “Walk Like an Egyptian” or “Express Yourself,” had been markedly eroticized. An increasingly common device paired fully dressed men, often in formal evening attire or official uniforms, with women in lingerie or bikinis. The music video had no monopoly on this formula, nor did it originate it—I give choreographer Bob Fosse the most credit for its popularity. (You can see an early example in Fosse’s mid-1950s staging of “Whatever Lola Wants” for "Damn Yankees," and he was still working out variations of the suit-meets-undies routine two decades later in his stylized work for "Cabaret," "Chicago," and "All That Jazz.") But this dance meme soon turned into a MTV staple and, for all its incongruity, proved irresistible to audiences. In Cher’s video for “If I Could Turn Back Time,” she prances around the battleship USS Missouri, backed by a cadre of uniformed sailors, while wearing an outfit better suited to lap-dancing than nautical pursuits. David Lee Roth sings “California Girls” to more than a dozen attractive young women in skimpy swimwear, but he is fully dressed, complete with stylish vest and bowtie. Madonna adopted a similar concept, portraying a peepshow entertainer in her video “Open Your Heart.”

These exercises in musical titillation each resulted in impressive record sales. Even so, artists found it harder and harder to achieve a sufficient level of shock and awe given the endless repetition of these sexually charged formulas. How could a megastar push the envelope without running afoul of MTV censors? Madonna found the combination of eroticism and Christian iconography stirred up some protests—and a healthy dose of publicity and sales. Some artists tested the waters by including homoerotic content, for example British band Frankie Goes to Hollywood, whose initial video for their hit song “Relax” was set in a gay S&M club. But edginess failed in its purpose if a video went beyond the established boundaries of cable TV fare. In the case of “Relax,” the band needed to shoot a second, much tamer video for their song.

Most of the controversies of the era arose from the visual images, not the songs themselves. I speak of songs here, but the artists of this period increasingly focused on creating recordings, not compositions, and often the recording itself was conceived from the start in conjunction with the potential for video realization. Anyone who simply studied the sheet music would almost always come away disappointed by the flimsy foundations on which hits were constructed, but by the time the team of experts and handlers had created the final product, the meager song had undergone a magical transmutation into an extravagant vehicle for the star performer. The themes presented in the lyrics of the leading songs were often highly conventional, recycling the same sentiments and imagery favored in decades past. The words of Robert Palmer’s “Simply Irresistible” and “Addicted to Love” could hardly be more banal, but viewers were captivated by flickering images of the artist, dressed like a successful banker, backed by a cadre of deadpan miniskirted and braless lovelies who looked as if each had been cloned from the same DNA. The tune “Rhythm Nation” is little better than an awkward chant for an imaginary country that couldn’t afford a real national anthem, but Janet Jackson’s leadership of a sexy paramilitary troupe of dancers turned it into one of the most riveting videos of the era, a kind of sensual steam-punk for MTV viewers. Madonna’s song “Cherish” not only reuses the title of a chart-topping single by The Association from more than twenty years earlier, but even mimics its opening words; and the reference to Romeo and Juliet in the lyrics—allegedly the song was partly inspired by Shakespeare—draws on an even older, if by now banal and predictable, romantic symbolism. Even so, the finished recording is catchy and danceable, and its strikingly Hollywood-ish video, with rolling-in-the-sand romance overtones of "From Here to Eternity," brought this appealing taste of pop-music candy to places the Bard of Avon never envisioned. Such was the fate of most of the popular love songs of the MTV age: the words embraced tired clichés, but the spectacle proved simply irresistible.

*

“Sex sells,” as I’ve heard over and over again. Whoever came up with that cynical two-word marketing plan must have worked in the music business. But even sex—or at least sexualized music—demands variety, and rising stars must find ways to work new variations on the oldest of themes. Girl bands in Asia now incorporate elements of cosplay, anime, action films, and gymnastics into their provocative performances. In the United States, Rihanna releases sexually charged videos dealing with everything from S&M to Russian roulette. Raising the ante still higher, Lady Gaga draws on the most extravagant elements of performance art, in both her music and public appearances, and discovers ever new ways of marrying the aural, the erotic, and the outrageous. As the situation warrants, she appears in a meat suit, inside a large egg, wearing a G-string and a bra made of seashells, or (Lady Gaga emulating Lady Godiva) nothing at all.

Perhaps the most powerful and recurring image in the twenty-first-century conception of the love song is that time-tested combination of the sharply dressed man with the mostly unclothed woman, the Fosse meme that refuses to die. This stylized conjunction of eye candy and fashion statement must somehow fulfill both latent male and latent female fantasies, or it wouldn’t keep coming back to haunt us. And it somehow retains the power, at least in its most extreme forms, to shock. When music critic Dorian Lynskey, writing in The Guardian, announced that Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” was “the most controversial song of the decade,” everyone knew that he wasn’t really talking about the song. This piece of beat-driven dance music offered little new or different—in fact many commentators complained that it sounded like a rehash of a Marvin Gaye track from 1977. The real controversy came in the visual images accompanying the Thicke recording. Two versions of the video were released, one in which the female models were barely clothed and the other in which they were mostly bare. In both instances, Thicke kept himself in natty attire suitable for a GQ shoot.

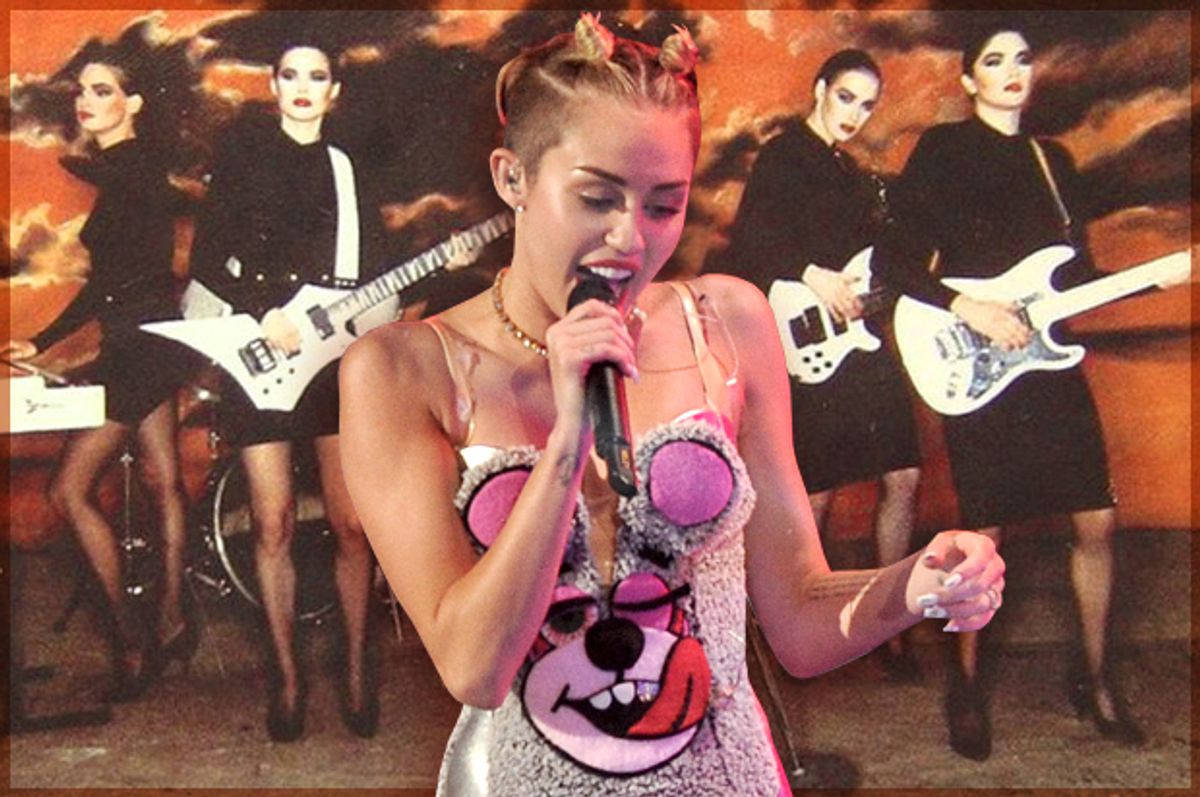

But these exercises in musical eroticism hardly made a stir when compared with Thicke’s televised appearance with Miley Cyrus at the MTV Video Music Awards in August 2013. Cyrus, who came to fame as a sweet-as-pie teen actress on the Disney Channel series "Hannah Montana," accompanied Thicke with dance moves that no doubt aimed at sexiness but achieved instead a strange rote and ritualistic quality, more like the courting ceremonies of marionettes. Turning her back on her dance partner, Cyrus bent over like a female cat in heat and rotated her buttocks in a move known as “twerking”—a word all but unknown before the broadcast, but heard everywhere in ensuing days. Wearing only skin-colored underwear, Cyrus sometimes accompanied her "dance" moves by waving a large foam finger, akin to the exaggerated phallus representations in some ancient art, and sticking out her tongue.

Somehow we’ve come full circle in our history of love songs. As you may recall, when we looked at the songs of the ancient Mesopotamian fertility rites a few hundred pages ago, we found many scholars asking the pointed question: Do these really deserve to be called love songs? The sexual elements were so heightened and the romantic trappings so noticeably absent, that we hesitated before applying the word love to the proceedings. Today we wrestle with the same question with regard to the most successful ‘love songs’ and are forced to ponder how, several thousand years later, we got back to the starting line.

Is this the inevitable result of the leveling impact of the web and metrics-driven algorithms that now dominate the music business? Face it, for a video to generate hundreds of millions of views in a few days and rise to the top of the heap, it needs to offer something that transcends national boundaries, cultural differences, language barriers, and varying tastes—and nothing manages that better than the brute force of biology. Should we be surprised that, turbocharged by these global technology platforms, aesthetics blurs into the basic instincts? The message of these videos is universal, no subtitles required, our receptivity literally coded into our DNA.

So is this the endgame of the love song? Are we seeing the final validation of Darwin’s claim that the drive to procreate plays the tune, and the rest of us just dance to the primal beat? Is survival of the sexiest the inescapable rule of the day, and every day to come—the formula for popular music that will always deliver superior metrics?

Perhaps. But I’m still not ready to write off romance. The rituals of courtship and the heady euphoria of emotional surrender are, in their own way, as alluring as the provocative sex come-ons of our viral videos—and with perhaps even more potential for aesthetic transformation. The narrative of love, with its endless complications and resolutions, offers more variety than even the most skilled courtesan can invent or digital Kama Sutra contain. When compared with the tangible qualities and overwhelming physicality of sex, the ineffable metaphysics of love must strike us as insubstantial, perhaps even a burdensome preliminary to the main event. But the heartfelt love song, yes even the wimpy love song, has overcome far tougher odds in the past, and if it has managed to surmount religious, political, and cultural obstacles during the course of millennia, it can certainly find a way around YouTube algorithms and the conventional wisdom of our hormone-driven music business. As this history makes clear, love has spurred many musical revolutions in the past and thus can probably set off a few more in the future. But another lesson, documented here again and again, is that when the upheaval arrives, when love finally calls the tune, it almost always comes from the least expected direction—from the bohemian, the outcast, the excluded, the marginalized and least powerful folks, and the most hidden places.

Reprinted from "Love Songs: The Hidden History" by Ted Gioia with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2015 by Ted Gioia. All rights reserved.

Shares