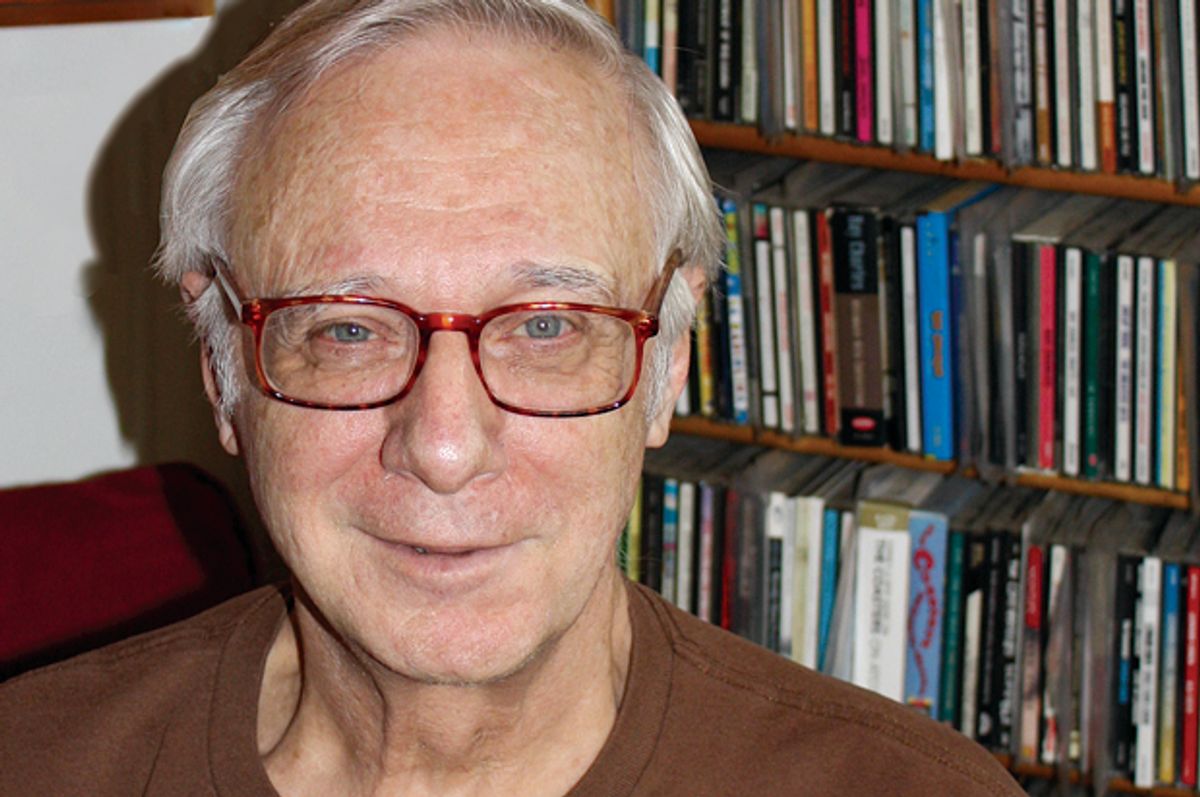

Robert Christgau started calling himself the dean of American rock critics around 1970: What began as a half-ironic youthful boast has become an elder statesman’s almost literal job description. Of the wave of formidable writers on popular music who hit in the ‘60s -- which also includes Lester Bangs, Greil Marcus and Christgau’s girlfriend Ellen Willis -- he’s always been the most succinct, the most pragmatic and the most rigorous. Best known for his Village Voice Consumer Guide feature -- short, chiseled little prose poems impersonating record reviews -- Christgau now offers a memoir, “Going Into the City: Portrait of a Critic as a Young Man.”

The book travels through his Queens upbringing, the intellectual jolt the preteen goy received from a batch of Jewish classmates, his youthful fascination with poetry and Dostoevsky, his time at "Animal House"-era Dartmouth, cross-country drives and conversations about sex, politics and Warhol, and his dedication to journalism in general and rock criticism in particular. The book gets near its halfway point before the author has enlisted at the Voice, which will be his home for decades until he is dumped by a new regime of corporate cowboys.

Christgau names names, writes so passionately about both the U.S. and U.K. edition of the Stones’ “Aftermath” it will make you want to find both and listen to them back to back, and gives one of the finest and most complex portraits ever of a female intellectual in his scenes with Ellen Willis, whose vision of pop -- and Pop -- profoundly influenced his. There’s something both boastful and oddly humble throughout: He talks repeatedly about the results of his childhood IQ tests even while later calling himself “a German hyperintellectual who’d learned manners from a fireman who ate dinner in his sleeveless undershirt.”

The result is a sometimes frustrating book that is also a consistently brilliant and fascinating one.

Christgau -- who under the influence of a glass of iced coffee was sometimes so intense that he would not let his interlocutor finish a sentence -- spoke from his home in New York.

Let’s start at the beginning, sort of. Unlike a lot of your peers in rock criticism, you’re not from the West Coast -- you’re not a Berkeley free speecher like ...

I don’t think that most of my peers in rock criticism are from the West Coast. I think most of them are from the East Coast.

Let me try to frame it. Some of the famous and storied rock critics -- Greil Marcus, Lester Bangs-- are from the West Coast. Others are Jewish bohemians like Ellen Willis. You come from a straighter world, don’t you?

Ellen Willis and I came from exactly the same background, Scott. That’s the reason we hooked up for three years. She was a policeman’s daughter from Queens. I was a fireman’s son from Queens. You can’t be much closer than that. We weren’t brought up as bohemians. We both became bohemians, as did many people in the early '60s.

OK, fair enough. You don’t feel that you’re in some ways different from that first generation of rock critics in your background? I’m just wondering if that shaped your tastes, et cetera.

The end of the '60s chapter has a three- or four-page section in which I break down the differences between myself and what I regard as the first generation of rock critics, which does not include either Marcus or Bangs because they all come in a little later. They came in in ‘69. This is through ‘68 and at that time the vast majority of rock critics were, in fact, New York Jews with a few Boston people. That’s the people I’m talking about. Even Jon Landau -- I can’t remember where he grew up at the moment -- but I know that he spent his childhood in Brooklyn and Queens then moved somewhere else. I don’t remember where.

And in that respect, yes. I certainly felt it was worth pointing out that unlike that early generation, I very unusually for an intellectual in Manhattan in 1965 grew up a born-again white Christian -- plenty of born-again black Christians -- but a born-again white Christian, and while I know former born-againers who are my equivalents, they come from other parts of the country. John Morthland came from a different kind of a background. Lester was a Jehovah's Witness, which isn’t the same thing but is kind of like it. Very much not the same thing actually but so, yeah. A very important part of my story far as I’m concerned is that I was this born-again Christian whose first salvation came through a class full of wise-ass Jewish kids in junior high school. That was the first chapter I wrote. I wrote it as the chapter I sent around because I felt if I couldn’t make that chapter work that I wasn’t going to to do the book right.

There are a lot of chapters that take place before rock 'n' roll hit or before rock 'n' roll hit you in a hard way. Why did it seem important to get back story about your family and your upbringing and childhood in here?

Because it’s a memoir. Because you are the product of your background, even if it’s by reaction. I had conflicts with my family but basically I remained in a loving relationship with them, even at the worst of it. Unless you are just pure rebel, it’s a combination of two things.

Though I don’t talk about it in the book explicitly, it’s clear to me that aspects of my upbringing remain with me and that’s the reason that when my wife and I got married, we put our parents in the traditional service where God usually goes. We were the products of loving marriages -- not perfect marriages but loving marriages -- and we had loving relationships with our parents and that made marriage seem like a plausible outcome to our lives and something worth pursuing. That’s a very, very important thing that happens in this book, in part because at the very core of my conflict with Ellen Willis, who I love deeply, and who loved me too, was that she didn’t believe in marriage. Her ideas evolved in other ways. She remained adamant about that to the rest of her life even after she was married. She claimed, and I see no reason to disbelieve, that the marriage she did eventually make with Stanley Aronowitz was strictly for tax and legal purposes, medical insurance in there, and that might be plausible to me. I don’t think she would deny and I don’t think Stanley would deny either, although I don’t know anything really about the details of the relationship except that I could see that they loved each other. Nobody wants to tell me about that. Why me?

But I was just saying to my wife the other day that as painful as the breakup was and as well-suited as Ellen and I were to each other in certain ways -- people said this for years after we split up. Why in the world did you guys break up? At least they said it to me. We both found far more suitable mates in the wake of that. She had a very, very serious -- it wasn’t a marriage. Fine. I don’t understand what her real vision of it was. Even though I read her writing about it, I don’t quite get it. I’m not going to start asking her daughter and widowed husband, but the idea was don’t get married. If you’re a feminist, you don’t get married. After we broke up, that was a really important difference between us, where she had persuaded me and then I spent three years figuring out that I really didn’t agree with her. Believe me. If you’re intimate with a mind as powerful as that of Ellen Willis, it takes you a long time to separate yourself from her ideas. She had an extremely powerful mind.

I can tell from the writing. I was going to take you there, in fact. For someone associated with bohemia, punk rock and other things, you have an oddly earnest and conventional view of what we would call bourgeois marriage. What led you to that?

I suppose it’s earnest. I don’t think it’s at all conventional. Insofar as it’s earnest, I’m proud to be earnest. I don’t care if that’s corny. Those corny adjectives? They all have their place in life. Is there some kind of a contradiction or disconnect between how much satisfaction I get from unconventional and apparently antisocial artists? Yes, there is. In some cases, they do a kind of vicarious kind of living for me. On the other hand, you might think I have a conventional view of marriage but put me in a town in a medium-size city in Kansas and I don’t have a conventional view of marriage at all. On the contrary.

My personal experience has been that in my free bohemian subculture, I’m not unique. My experience of what a loving relationship is like rings true with a lot of people I meet. I have a theory that the people you meet, one way you choose them, is their suitability for you in that particular matter. Attitudes toward friendship and marriage are in many cases closely aligned. So I can’t say that my sample is a fair sample, but all I knew was that I kept reading people being blasé about infidelity. Not necessarily saying this is great but it happens, from sophisticated people. In my world, infidelity is a disaster. Always. I was not about to pretend that it wasn’t.

There’s a story early in the book about my friend and mentor Bob Stanley who imbued a sort of -- he was very interested in sex. Painted erotic paintings. He gave me the idea that, yes, people fuck around -- and then Ellen and I both found ourselves being unfaithful to each other about 10 months into our relationship. I could not believe how much it hurt. I couldn’t believe the pain I was in, so I went to Bob and he said, of course it hurts. It always hurts. And as I say, this was real, Now he tells me stuff. Suddenly I realize this guy who I admired enormously and admire him even more enormously now and miss him terribly -- he’s been dead for almost 20 years -- I loved still. I still love him. Nevertheless, he was trying to act cool for me in some kind of way. I said to myself I’m not doing that. He misled me here so he could look cool. I’m never going to do that.

I’m a member of a generation -- I was born in 1969 -- whose childhoods were dominated by infidelity and divorce by the parents. I’m an example of that and so is my wife. I applaud you doubling down on marriage, however conventional it may seem. I wish more bohos and lefties would do that.

I went into this book knowing I was going to do this. I think I didn’t know quite how much I was going to do it. It is in terms of memoir unconventional. But what could I do? I told the story I had to tell. You know that thing that novelists say about how the character takes over the story? The story took over at a certain point. That was the story and I tried to make it as credible and coherent as I could.

There’s also in addition to music and bohemia -- and there’s a wonderful passage about jazz and foreign film -- there’s also a lot of sex in the book.

I don’t believe there’s a lot of sex in the book. I don’t believe you will ever find a single passage where there are two consecutive sentences about it. Why? Because as far as I’m concerned, once again in my experience, I can’t say that this is true of all my friends because people are remarkably reticent on this topic. But as far as my wife and I, our relationship is a sexual relationship. As far as we’re concerned, marriage is a sexual relationship. I don’t believe that you write about sex by generalizing it. I believe you write about sex the way you write about everything else. I tell my students that they should be concrete when they write and that’s why so many are saying -- in what seems to be a rather prurient and squeamish way -- that there’s a lot of sex in the book.

I may have forgotten something. The scene in Jamaica. There’s a thing about Jamaica. That wonderful week we had of fucking in Jamaica. That’s more than one sentence there and I bet I could find something else, but in general, these are details meant to evoke, just as it's meant to evoke when I say, as Mark Athitakis has the discernment to quote today, our house wasn’t the nicest on the block, but it was the second nicest on our side. It wasn’t just a detail. It’s meant to situate me in a certain way. We use details in a narrative and I don’t believe there are wasted details in this narrative.

Let’s go back to music for a minute. It’s probably easy for somebody younger, who grew up in the '80s and '90s, to look back at the '50s, '60s and '70s and think that for a little while at least, the good stuff and the popular stuff overlapped. I’m talking about pop music. I’m also thinking about the first two "Godfather" movies and a handful of other things. Is it fair to say that that really happened or is that just a nostalgic fantasy? In other words, did the good stuff and the popular stuff start to diverge at some point? They broke apart, where we got great work and popular work that were not often the same thing.

Well, I would certainly say that the mid-'60s, in particular, and to a lesser extent-- what I’ll call for a moment the high '50s-- late ‘55 to early ‘58, because that’s actually how it breaks down-- that was really true. Let’s label it. I’d have to look at the numbers. But the '60s, say from Beatles time or even a little before up to ‘67 or ‘68, that was a time where you could turn on the radio, even though there was some crap there, and there was really an enormous amount of good music. That was a kind of golden era.

On the other hand, the notion that no current popular music is of quality is philistine. Both Beyoncé and Jason DeRulo were in my top 10 this year. They are pop artists. Black pop artists -- who tend to be better than white pop artists (although not consistently always true). But in general, if you believe as I do that the most vital popular music for the past 30 years has been hip-hop, there’s a lot of hip-hop that gets on the radio and makes the charts that I don’t think is any good at all. I don’t get it. Or there’s this good single but the album is terrible.

Kanye West, Jay Z, Lil Wayne. Not true. Great artists. Three of the great artists of the past 10 to 15 years. Very popular artists. That leaves hip-hop out of it. In white rock, it’s been true for a long time. I suppose you could say Lorde might be an exception to that. I think she’s half an exception. On the other hand, I’m also a big Iggy Azalea fan. But we’re back in hip-hop again even though its a white --.

So you’re saying that in white rock, the popular stuff and the good stuff isn’t --.

The fact of the matter is that at this point, what white rock are we talking about that’s popular? Are we talking about U2 and the Foo Fighters? Springsteen, who still has moments, for sure. There was that album last year. I respect him enormously, and I think I could think of an exception of two more. That’s true. At this point, are we really lamenting the guitar band? The guitar band is doing a lot better than people believe but it definitely has become -- as has been true for 20 or 30 years -- primarily a realm of what I call the semi-popular. That’s been true for a long time. What isn’t true is when people say there are no good bands of that sort of semi-popularity anymore.

I guess part of what I like about your work is that you continue to be enthusiastic about different kinds of music. I wonder, though, if anything hits you these days, or in the last decade or two, hits you as hard as something like [Television’s] “Marquee Moon” did the first time you heard it.

I mean, "Marquee Moon." That’s a very high bar. Why don’t we instead say [the Ramones’] “Rocket to Russia”? A slightly lower bar but still a great record. The answer is yes. For sure, this band Wussy, who I’ve been raving about since 2005, definitely qualify. I think they’re as consistent a rock band and song band I’m going to have to say as music has even produced. They’re six in and they’ve never made an A- album. It’s all A's. The Ramones did that for four in a row. Not easy to do in my world. My system. So there’s that. And do they hit me as hard? Yes, they do.

But there is something about things hitting you hard, although you’re younger than me ... The older you get, the less likely it is that any one thing will hit you hard because your hard drive is already jammed with other stuff and that’s just a physiological reality. Insofar as music being a physical experience, you can’t possibly be as open to it as I was to the first side of Bill Doggett's "Honky Tonk" lying on my living room floor when I was 14, which was a formative experience for me and I play that record today and it still does that to me. I know every second of it and I love hearing it every time I play it. I suppose if I play it three times a day for the next month, I might not feel that way. But it imprinted itself with a depth that even Sleater-Kinney, on their newest and arguably their best record, can't do. It can't. Because music that you latch onto as a child and an adolescent ... You were born in ‘69? You like punk rock and you like Talking Heads. That’s going to be it for you. For you, that’s honky tonk. And there’s nothing you can do about it. And it’s not a bad thing, those memories. It’s great.

You’ve got a great line early in the book where I guess you’re talking about commercialism and your commitment to taking commercial music seriously. You say -- I’m reading from page 9 -- “Pop didn’t work out as well as we’d hoped. That’s for sure. But as cynical reactionary money-bags launched a counterattack on idealistic counter-culture lazy bones that necessitated among other vile maneuvers, new degrees of corporate integration in the culture industry itself, our political fantasies worked out even worse. That was the real problem.”

I love that passage but also wish you would run with that a little more. Can you tell me where you were going with that?

I believe I should find it in my own book here. Like a fucking idiot, neither of my reading copies is here ...

First of all, I’m using pop in that particular case not as pop music but as the notion of Pop which I took from the Pop artists. Ellen latched onto that as a basis but not the only basis of the notion. She was a Warhol fan, too. We developed this theory that I explain we never fully articulated and might have had a damn bit of trouble doing, but we broke up before we could even try, in which -- let me try to phrase this right ... The market for popular culture had an inevitably progressive effect on the production of popular culture that we both believed -- she’s dead, I can’t check with her -- that here was something built into the way consumption worked that compelled the producers to do better stuff because there was a feedback loop between the artist and the audience that made that happen.

There are two things we did not take into account. One of which was that the economy was about to stall. That begins in ‘69 or ‘70, I think. I think as a perception it doesn’t become important until probably the oil crisis of ‘73. But sort of subliminally it’s happening. And the other thing is how smart capitalists are. Who knew that the [Black-Scholes model] -- what is it called? The derivatives formula that ultimately ruined the world economy? We weren’t smart enough to know that any of that was happening and neither was anyone else.

But definitely we weren’t, and so those two things meant that those market mechanisms, which were real, were far more temporary and far less reliable at that moment. That ultimately becomes political and pop turned out badly, but politics turned out worse. Ellen and I had very different views about how that worked because she was always more of a leftist. I’m a leftist too but she was much more of a leftist. She ended up marrying the man who ran for governor on the Green Party and that was kind of a meliorist move on his part. That was moving right for Stanley, who I respect enormously.

Let me throw two more big questions at you and then we’re done. You lived through huge changes in journalism, in the alternative press, in the world of criticism. I wonder what you think has changed in the big picture between, say, the '50s, '60s, '70s--?

Oh, for goodness sake. You gotta nail it down. That's a 1,000-page book that doesn’t even get it all.

I’ll be more specific. You worked for the Voice under several regimes. My hunch is that change that brought the end of your career there -- the cowboys from Phoenix -- was not just about a bunch of obnoxious people. It was about a cultural change. Is that fair to say?

It’s not a cultural change. It’s an economic change. No, no. Not a cultural change. It’s about economics.

What changed then? You, Giddins, all these other incredibles critics and thinkers being in papers like the Voice, to a world in which people like you are pushed out, laid off, etc.? It’s not a cultural change? It’s just a purely economic shift?

Well, certainly one factor in how all of that happened is that profit margins became thinner and thinner in journalism and particularly in my field because a) the Internet reduces the cash value of the written word, and b) it reduces the cash value of recorded music. So there, payment for me is thereby seriously damaged in two different ways. But in particular, the Voice got sold because David Schneiderman thought he could see an empire in front of him. It wasn’t a bad idea, but it did not allow for Craigslist.

Who did? Nobody saw that coming.

Who did? Nobody. In a piece that Mark Jacobson wrote for New York magazine, he said that in almost so many words. Similarly, well, no -- that just flew the coop so let’s stop there.

It sounds like you’re not saying that we as a society decided that criticism was less important, but there was an economic shift that made it more difficult to support in a commercial outlet like a weekly.

As I believe I’ve said previously in this round of interviews I’ve been doing, journalism was the devil’s bargain with advertisers. Advertisers found that they didn’t need as much as we do. To me, that seems like a crucial factor. Then we can go to some other place and ask whether everyone reviewing a book on Amazon or whatever it is diminishes the value of criticism in other ways. And there are ways. That’s a more complex matter in which I am more poorly informed. And while certainly, granted, in some general way that happened, I don’t think I know enough about it.

Good. Let me conclude with a last question that tries to wrap some of this stuff up. In the '80s and '90s, anywhere a reader could find the Voice or a weekly like it, they could read you or someone like you evangelizing for the Go-Betweens or the Indestructible Beat of Soweto or Yo La Tengo or whatever. You could find Gary Giddins writing about an Eric Dolphy reissue. Dargis or Hoberman on some obscure foreign filmmaker.

Now, whether it’s dailies or weeklies or whatever, a lot of criticism and cultural coverage is about corporate pop, mainstream movies, what people wear at the Oscars, that kind of thing. What’s changed besides the money and corporate ownership? Is there something that’s changed in journalism and American culture or is it just about ownership?

I’m sorry to say that I don’t feel prepared to generalize about that subject. For one thing, I don’t have a unified theory of everything, and I’m extremely reluctant because of intellectual history to go bitching about how culture has been devalued. I’ve seen people who say that be wrong too many times, or about Iggy Azalea at this very minute and I bear that in mind.

There are things about it that I really don’t feel I understand. The whole notion of what the actual economic model, and there I go back to the money, for online journalism is -- we’re 15 years into it. I don’t think anybody has any idea what the fuck they’re doing. People are just doing different things and as has always been true, some people just keep doing them even though they don’t work so well because they’re idealists or they have a vision or they believe in something. I would say that Salon is a perfect example of that. The fact that Salon still exists, some 17 years or something like that.

I think it was ‘95 that it was founded.

Well that’s 20 years! That is a tribute to its owner, to Joan Walsh, because they kind of grit their teeth. God knows what you’re getting paid for this, you poor motherfucker. I have my problems with the ideology of Salon at some level but I admire their grit. Its grit and its ability to do something that approximates quality journalism. On business models, I bet you hear about far more than I would want to. I’m sure you hear about your business model all the time and I bet it’s a troubled one. But there is in fact just a level of emotional commitment, which has always made a certain type of good journalism work and Salon is not the only place that’s happening online.

I don’t know enough about the other places. I know they’re there and I just know there’s money being thrown at this and that and who the hell knows how long anything is going to last. I don’t believe any journalist who has a job now should believe he’s going to have it in a year. Or she. That doesn’t mean they won’t. Most of them probably will. But it’s a very, very fluid business environment.

Shares