Back in 1991, a youngish novelist named Nicholson Baker decided to write a book about his favorite author, John Updike. The result, "U and I," was an odd and enchanting mixture of hero worship, self-analysis, and lithe literary criticism.

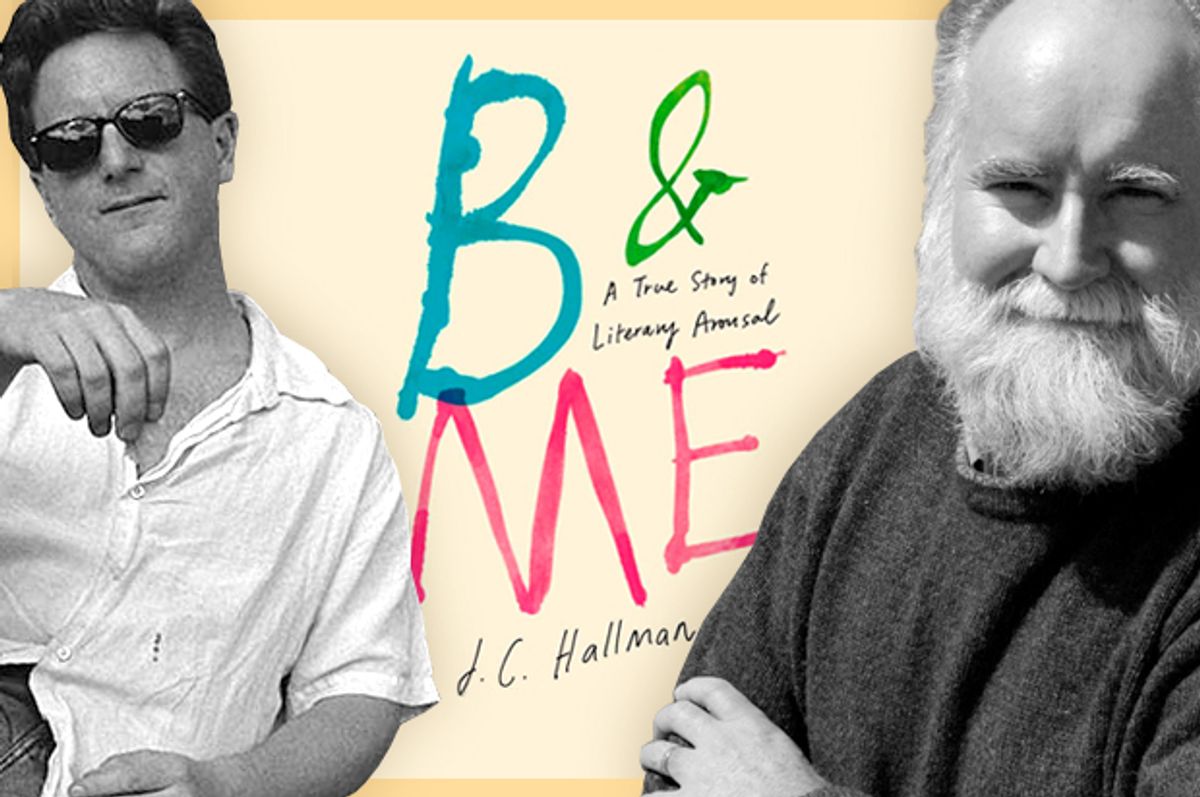

"U and I" inspired an entire genre of books about the pleasures of reading, none stranger than J.C. Hallman’s brand-new "B & Me," which, as karma would have it, chronicles Hallman’s relationship with the no-longer-youngish Nicholson Baker.

To say that "B & Me" is an odd book doesn’t quite do the project justice. In fact, Hallman had never read any of Baker’s work when he decided to embark on a survey of his career. Stranger still is the approach he winds up taking, which is both intensely confessional and openly carnal. “What I really wanted to do with Nicholson Baker,” Hallman writes, “was have Emersonian sex with him.”

He writes about Baker’s trio of NSFW books—"House of Holes," "Vox" and "The Fermata"—but also about analingus, masturbation and ejaculation, sometimes in relation to his girlfriend Catherine.

As provocative as this material is, Hallman’s inquiry has a deeper agenda. It’s a love letter to the book as a physical object, a source of intellectual ardor, and a form of emotional salvation. On the eve of "B & Me’s" release, Salon sat down with Hallman to talk about author photos, the conventions of literary criticism, and, of course, Nicholson Baker’s penis.

How did you conceive of this book? Specifically the idea of writing about an author before you’d even read his work. It’s pretty much the opposite of the standard approach.

A few years ago, I started to get interested in how writers write about books, as opposed to critics. It turned out there was a whole hidden tradition of “creative criticism,” which is really just stories about our reading lives that are dramatic, passionate, funny, angry, sad, sexy or whatever. But even in these books I found writers reflecting on a lifelong preoccupation with a given author’s work. But what about telling the story of a literary relationship from its moment of conception, the moment when you first hear of an author and decide that you have to seek them out. This moment is common—we all go through it hundreds of times—but no one had ever written about it. When I realized that Nicholson Baker was part of that hidden tradition of good writing about literature, I knew I should seek out his work. And that was the moment I sat down and started writing "B & Me"—before I read a word.

But weren’t you worried about seeming like a dilettante? Or at least someone engaged in a kind of stunt? After all, you’re a respected critic who is arguing in this book, quite strenuously, for a more vigorous engagement with literature. Doesn’t it seem incongruous to spend so much time on issues such as the covers of Baker’s books? Or his author photographs? Couldn’t a reader who likewise cares about deep literary engagement complain that you devote too much time to your own superficial responses and whims, and not enough to investigating Baker’s work?

Well, when I started reading—and I began with "U and I," which a number of early reviewers regarded as a dilettantish stunt—I realized that I couldn’t just repeat what Baker had done, no matter how much I admired the book. And really "B & Me," even if it’s similar in tone, is the exact opposite of "U and I." Rather than Baker’s “memory criticism,” which lets him write a whole book about Updike without ever returning to Updike’s work at all, I chronicled the experience of reading Baker front to back, conducting careful evaluations of each book along the way and attempting to plumb the thematic threads that stretched across his entire career. I hope that’s vigorous enough!

As to photographs and book jackets, why should they be off limits? Does not a great deal of thought go into them? Aren’t they, really, front and center to our experience of books and authors? At a time when the physical object of the book is under threat, I don’t think it’s superficial at all to suggest that additional meaning might be drawn from too-often overlooked features of our reading experience.

I’m not sure author photos and covers are “too-often overlooked features,” or that they qualify as part of “our reading experience.” They seem to me part of a larger effort to celebritize the writer rather than focusing on the work itself. That said, I absolutely understand what you mean about the book as a physical object. It made me wonder how you felt about the prospect that a lot of folks will read "B & Me" as an electronic book?

To my mind, an e-book is, simply, less than a physical book. It’s not an invalid experience, but it’s a lesser experience. Reading a physical book is more dynamic, robust and meaningful (and, in support of this, there was that recent study on brain activity while reading books vs. e-books—books generate more or better brain activity). Incidentally, it’s worth noting that Nicholson Baker has been thinking, and writing, about the impact of the digital revolution on literature for many years. Far more distressing than the thought that people might read "B & Me" as an e-book is the recognition that Baker’s book, "Double Fold," about the digitization and destruction of library books, can be purchased for the Kindle for $11.84.

One of the aspects of the book that’s so fascinating is how much Baker infiltrates your erotic life. I assume you chose the subtitle (“A Literary Arousal”) and, man, do you back it up. You write about your sex life and Baker’s role in your sex life. You write about Baker’s sex life, even his genitals. Was your decision to “go there” a function of Baker’s own preoccupation with the erotic? Do you worry about other critics dismissing the book as prurient?

Well, yes—the fact that Baker himself had written three books straddling the line between pornography and literature meant that I had to figure out how to react to this part of his career (and to be fair, I address Baker’s sex life/genitals only to the extent that they pop up, repeatedly, in his work).

But it turns out that all of these books are elaborations on an age-old reading-as-sexual-encounter metaphor, and so there is no moment of explicitness in my book that does not get used as a way of reflecting back on our experience as readers. This metaphor pops up everywhere. For Emerson, literature is “creative,” just a hitch step from “procreative.” For Proust, literature is an “enticement,” just a hitch step from “excitement.” Yet we’ve abandoned our ability to write about this. "B & Me" does not approach the explicitness of Lena Dunham’s "Girls" or Lars Van Trier’s "Nymphomaniac," but in the context of “criticism,” what I’m doing could well be regarded as taboo.

But I think Alfred Kazin was right to worry, in 1961, that literature and criticism was even then having a hard time figuring out how to matter, and I don’t think we do books and literature any favors but cutting them off from any part of our lives. Indeed, books matter precisely because of their intimacy, because of the way they inform every aspect of our experience. What I did was dramatize that, rather than leave it as dry academic observation.

Wow! That’s a lot of hitch steps! But your point is well taken. When we allow books to deeply affect us, that’s happening at every level. In that sense, I love how risk-taking "B & Me" is, because it seems to take those risks on behalf of literature. Another thing I admire about the book is that it’s not just a piece of criticism, or a cri de coeur, but a memoir. A lot of the book really is about your relationship with Catherine, and whether you’re going to make a life together. I even worried a little on your behalf, because it’s such a raw accounting of your affair. I kept thinking: God, what if they break up? Won’t it be tough to read from the book? Won’t it be tough anyway?

I wanted the book to be interesting just on the level of its being a story. We should never write about ourselves just to write about ourselves—we have to make ourselves vulnerable, and there needs to be something at stake for us, just as in a fiction. So, really, there are two love stories in the book. The story of loving an author, and the story of loving a romantic partner, and the way the two interact demonstrates how literature matters, how it wends its way into our lives. Or that’s the idea, anyway.

And yes, there are sections of the book that I find it difficult to read out loud to myself (which I often do as I write). That said, I argue in the book that what we should explore in literature is that which we cannot or will not explore in any other precinct of human discourse. Neither live readings, nor interviews! So, for readings, I will have to pick my spots carefully—it’s a tough book to excerpt, but I think I’ve found a few spots.

Have you shown Baker the galleys?

Yes, he’s seen the book. I didn’t know it at the time, but he was informed about the project very early on, when it was still in proposal. When I finished the first draft, I was very worried about what he’d think. I’d gone out on all kinds of limbs, just on the level of facts (relying, for example, on quotes in interviews when, for all I knew, he’d been misquoted), and so when we decided to show it to him, we offered to send him the finished book, or a list of questions. He opted to read the book. I heard back from him about a week later. I don’t think I should speak to the contents of that note, but I’ve contemplated having it tattooed on my back. He was very gracious.

You’ve had a pretty wide-ranging career as a writer—nonfiction, criticism, fiction. What’s next on the docket?

I’m taking a pretty wide turn with the next book: I’m writing about a couple of really wild stories from the small, sub-Saharan nation of Swaziland, lodged between Mozambique and South Africa. I spent five weeks there last year, and I’ll be going back this summer. Loosely, it’s a book about literature in that Swaziland was part of the inspiration for the “lost world” sub-genre of adventure writing, and, to give you some idea, I’ve just spent a couple weeks trying to find out as much as I can about a man named M’hlopekazi, who is supposed to have been a Swazi prince and the model for an important character in the work of H. Rider Haggard ("King Solomon’s Mines," "She," etc.). There’s a lot more to it, obviously, but that’s what’s up next. For right now, it’s called "Land of Pulp and Sugar."

Shares