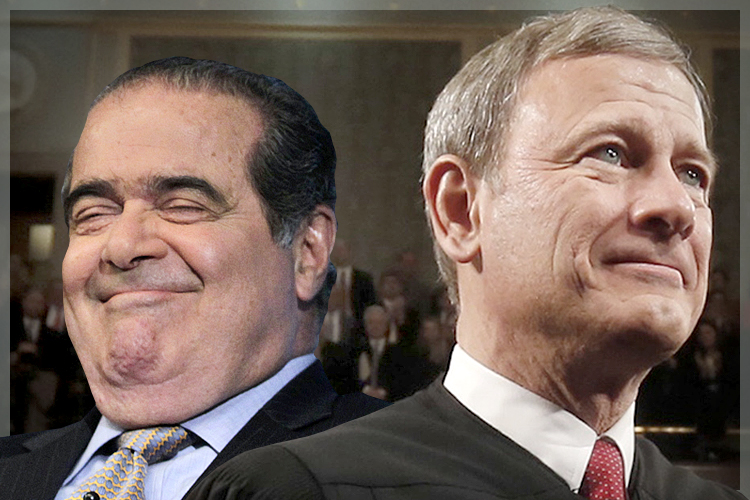

When discussing race, the conservative argument is best expressed by the famous words of Chief Justice John Roberts: “The best way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” Translation: America has done bad things in its history, but those bad things are gone now, so we should move past those horrors and look forward.

Conservatives believe that if blacks and Latinos simply work hard, get a good education and earn a good income, historical racial wealth gaps will disappear. The problem is that this sentiment ignores the ways that race continues to affect Americans today. A new report from Demos and Brandeis University, “The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters,” makes this point strongly. The report shows that focusing on education alone will do little to reduce racial wealth gaps for households at the median, and that the Supreme Court, through upcoming decisions, could soon make the wealth gap explode.

Wealth is the whole of an individual’s accumulated assets, not the amount of money they make each year. As such, in his recent book, “The Son Also Rises,” Gregory Clark finds that the residual benefits of wealth remain for 10 to 15 generations. To understand why that matters, consider the fact that Loretta Lynch, Obama’s recent nomination for U.S. attorney general, is the great-great-granddaughter of a slave who escaped to freedom. (That’s four generations). Consider also that most people on Social Security today went to segregated schools. (That’s two generations.) If Clark is correct in his thesis, then the impacts of wealth built on the foundations of American slavery and segregation will continue to affect Lynch’s great-great-great grandchildren.

It is therefore unsurprising that addressing just one aspect of this disparity cannot solve racial wealth gaps. Demos/Brandeis find that equalizing graduation rates would reduce the wealth gap between blacks and whites by 1 percent, and between Latinos and whites by 3 percent at the median. Equalizing the distribution of income would only reduce the wealth gap by 11 percent for blacks and 9 percent for Latinos. Part of the durability of wealth gaps is the disproportionate benefits that whites still enjoy: They face less job market discrimination and are more likely to reap a big inheritance, for example. This means that the returns to education and income are generally higher for whites. But even after controlling for these returns, income and education can’t explain the entire wealth gap.

Because America’s primary vehicle for wealth accumulation is our homes, much of the explanation of the racial wealth gap lies in unequal homeownership rates. According to the Brandeis/Demos analysis, equalizing homeownership would reduce the racial wealth gap by 31 percent for blacks and 28 percent for Latinos. This effect is muted because centuries of discrimination—including racial exclusion from neighborhoods where home values appreciate, redlining, and discriminatory lending practices—mean that people of color are segregated into relatively poor neighborhoods. Indeed, in 1969, civil rights activist John Lewis bought a three-bedroom house for $35,000 in Venetian Hills, Atlanta. He and his wife were the first black family in the middle-class neighborhood. In his book, “Walking with the Wind,” he notes that, “within two years… the white owners began moving out.” Had the value of his house simply kept up with inflation, it would be worth $222,881 today. But Zillow shows that three-bedroom houses in Venetian Hills, Atlanta, are currently selling for around $65,000 to $100,000.

Systematic disinvestment in communities of color means that even when blacks and Latinos own their homes, they are worth far less than white homes. In addition, blacks and Latinos are targets of shady lending. They are more likely to be offered a subprime loan even if they are qualified to receive a better rate. In the wake of the financial crisis, big banks like Blackstone scooped up foreclosed homes and are now offering them to people of color to rent, further pulling wealth out of these communities to benefit rich whites.

The financial crisis had a disparate impact on people of color. A Center for Responsible Lending report examined the loans originated during the subprime boom (2005 to 2008), and found that blacks and Latinos were almost twice as likely to have foreclosed during the crisis. The New York Times reported that Wells Fargo “saw the black community as fertile ground for subprime mortgages, as working-class blacks were hungry to be a part of the nation’s home-owning mania.” They discovered that loan officers “pushed customers who could have qualified for prime loans into subprime mortgages” and “stated in an affidavit… that employees had referred to blacks as ‘mud people’ and to subprime lending as ‘ghetto loans.’”

These problems are troubling, but, as unlikely as it seems, things are about to get even worse. The Supreme Court is set to decide Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, a landmark case challenging the disparate impact test, which allows a practice to be considered discriminatory if it disproportionately and negatively impacts communities of color, even if a discriminatory intent can’t be proven.

The case involves an excellent example of why disparate impact is so important: Nearly all of the tax credits that the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs had approved were in predominantly non-white neighborhoods. At the same time, the department disproportionately denied the claims in white neighborhoods. A federal judge decided that regardless of racial intent, the result had a “disparate impact” and increased neighborhood segregation. As Nikole Hannah-Jones has extensively documented, disparate impact has been crucial in holding banks accountable. For instance, the Justice Department used it to settle with Bank of America for $335 million after it was discovered that a mortgage company purchased by BofA had been pushing blacks and Latinos into subprime loans when a similar white borrower would have qualified for a prime loan. Because there was no official policy that required blacks and Latinos to get worse loans, the case would not have been won but for the disparate-impact statute.

The Supreme Court has already decimated the Voting Rights Act, opening the door for onerous restrictions on voting. They upheld a law banning affirmative action at state universities and have already crushed integration efforts at K-12 schools. Worryingly, as Demos Senior Fellow Ian Haney López told ProPublica, “It is unusual for the Court to agree to hear a case when the law is clearly settled. It’s even more unusual to agree to hear the issue three years in a row.” Given the importance of neighborhood poverty to upward mobility and wealth building, this case had the potential to be the most destructive, dramatically curtailing opportunity and making the wealth gap into a chasm. As Patrick Sharkey notes, “Neighborhood poverty alone accounts for a greater portion of the black-white downward mobility gap than the effects of parental education, occupation, labor force participation, and a range of other family characteristics combined.”

Demos and Brandeis suggest policies to boost homeownership, like better enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, lowering the cap on the mortgage interest deduction so blacks and Latinos can benefit and authorizing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to allow homeowners to modify their loans. In addition, America needs to systematically invest in poor neighborhoods. Equalizing public school education funds for poor and nonwhite schools would increase home prices in poor neighborhoods. In addition, a baby bond program would directly reduce wealth gaps by giving children money that could be used for a down payment on a house or an investment in their education. What’s clear is that we cannot simply hope that wealth gaps will disappear. These gaps were created by racially biased federal policies and need to be remedied by public policy as well. Government created the white middle class in the 1950s; now it’s time to create a black and Latino middle class. The Supreme Court, with its supposedly race-neutral philosophy, will only make it more difficult to close racial wealth gaps.

Catherine Ruetschlin is a Senior Policy Analyst at Demos and co-author of the report “The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters.“