As budget votes get going this week, keep an eye on the three most magical letters in Washington: OCO. In an era where so many politicians harp on “removing the burden of debt from our children,” OCO – which stands for Overseas Contingency Operations – represents an escape hatch. Put money into OCO and it doesn’t count as spent, at least not against the constraints Congress has shackled itself with for four years. It’s a great deal – as long as you’re part of the military.

“It’s basically crack cocaine for the Pentagon,” said Gordon Adams, a professor at American University who worked on defense budgets at the Office of Management and Budget during the Clinton administration. “It gives you a flexibility that most domestic discretionary agencies would kill for.”

OCO has created a double standard for D.C.’s insistent deficit conversation. Domestic spending must be held down, without gimmicks, games or tricks. But you can keep the military base budget static, load up the OCO, and use that money on virtually anything the Pentagon does. Congressional Republicans’ OCO end-around in this budget resolution, attempting to please deficit hawks and war hawks at the same time, borders on the absurd. But everyone is guilty of riding the OCO train – the armed services, the State Department, even the White House.

The development of OCO represents a new mechanism for funding American wars since 9/11, another gift handed out by the George W. Bush Administration. “There’s no prior instance of such a thing in American military practice,” said Gordon Adams.

Previous wars were funded first with a supplemental spending bill, outside of the budget cycle, usually for 1-2 years. Congress could put restrictions on the supplemental, like the scope of the spending, or reporting requirements. If the war continued, the Defense Department would fold the cost of maintaining operations into the overall budget. Once you’re in a war for a couple years, you can pretty well determine how much it costs to keep it going.

Afghanistan and Iraq changed all that. The Bush White House just requested one supplemental after another, claiming it was easier to not plan within the base budget (not planning was a core competency of the Rumsfeld-era Defense Department). It also became easier to get the “emergency” money, amid demagoguery about supporting troops in harm’s way. “Nobody ever cut a war supplemental,” said Gordon Adams. “It’s the aphrodisiac of the budgetary process.”

Over time, the Pentagon started to include things in supplemental requests like ordering an F-15, when no F-15s were shot down in Iraq or Afghanistan. All the money was fungible, able to be moved inside or outside the supplemental budget. You could call it a slush fund or an off-balance-sheet vehicle, but it enabled regular military spending to grow without scrutiny.

The Obama Administration promised to change all this. They gave the war supplemental budget a different name: Overseas Contingency Operations, or OCO. Gordon Adams worked on the defense budget transition at OMB, and he helped create a tight list of what could count in OCO and what couldn’t, which the Pentagon endorsed. Everything else would have to stay in the base budget.

This framework came crashing down after 2011. That year, President Obama signed the Budget Control Act, creating a spending cap for domestic and defense discretionary spending. But critically, under that law, OCO was considered emergency funding, standing outside those caps. The idea was that you couldn’t keep national security beholden to a spending constraint. But what this did in practice was loosen the reins on what could be considered OCO, to keep military projects funded while its budget appeared to be capped. The Pentagon base budget has gone down in recent years, but OCO balances things out, especially because OCO typically overfunds what is actually needed for field operations, with the extra money flowing back to the Pentagon.

“Here’s an example,” Gordon Adams told Salon. “OCO is spending $200- to $300 million on fixing propellers on nuclear submarines. That couldn’t possibly be related to Afghanistan. The last I saw, it was a landlocked country.”

Three-quarters of OCO funds “operations and maintenance,” a huge category into which the Pentagon can slide all kinds of spending. The Defense Department quietly survived sequestration pretty well, because OCO money filled in any gaps the arbitrary cuts created, without having to go back to appropriators to get clearance to use it.

As OCO became more of what Gordon Adams calls “magic money,” the White House got in on the act. They created a $5 billion counterterrorism account and stuck it in OCO, keeping the fund alive even after Iraq and Afghanistan end. The $1 billion “European Reassurance” fund to support Ukraine came out of OCO. Three thousand troops to West Africa to handle Ebola? OCO. $500 million to train the Syrian opposition? OCO. Even State Department funding has gone in OCO, as much as $7 billion, over 15 percent of their total expenditures.

Congress found the key to unlock OCO too, as a way to bulk up military spending and reward constituents with defense contract jobs while continuing to preach the gospel of fiscal responsibility. “It really has become crack for everybody now,” Gordon Adams said. “Everybody has discovered the miracle of OCO.”

Incidentally, the only “emergency” budget item that increases domestic discretionary spending outside caps is FEMA. And there are far greater reins on how FEMA money gets used. It’s less slush, more fund. So only defense contractors reap the benefits of end-running the budget cap. There shouldn’t be a budget cap at all, but certainly not one that only matters on the domestic and not the defense side.

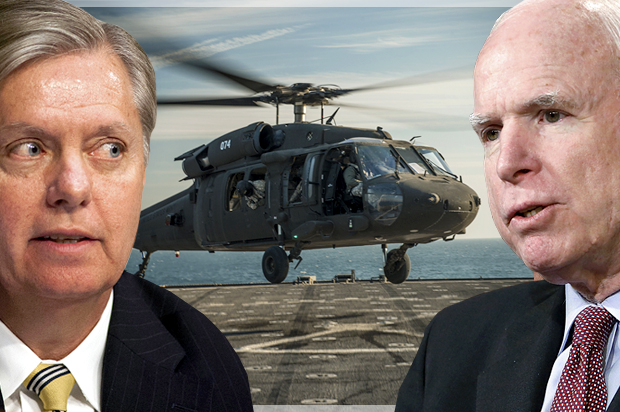

The GOP’s budget resolution for fiscal year 2016, due for votes this week, takes the OCO ploy to the extreme. The House designated $96 billion to OCO, $38 billion above the White House’s request, keeping the base budget capped, while flying past it with “emergency” spending. It’s a gimmick, John McCain thundered. Until he decided to go along with it, saying, “I will consider anything to get the numbers up.” And McCain’s good buddy Lindsey Graham copied the House, passing an amendment to the Senate budget to plus-up OCO. Remember that the same lawmakers who voted for that believe we can’t afford to feed hungry people in America.

One lone politician calling out the hypocrisy of all this is Senate Budget Committee ranking member Bernie Sanders. “These guys are saying we have to cut Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid,” Sanders told Salon on a recent conference call, “but when it comes to military spending, no problem, we can add it to the credit card.” Sanders planned to put forward an amendment to address the OCO gimmick on the Senate floor this week, but passage is unlikely.

The real question is whether we need OCO at all. It’s convenient for everyone involved to install a piggy bank for inflicting global war (except for the people dying). But the whole point of Congress having the power of the purse is to exercise discipline on the process, to make it hard to fund war. “My preference would be to go back to regular order,” Gordon Adams said. “When you encounter a need, seek specific funding for that package.”

The Congressional Progressive Caucus budget does this, ending OCO emergency funding. But Congressional leaders would typically rather not have to take such tough votes on individual war activity; they’ve delayed an authorization for action against ISIS for months. They’d rather just create a revolving cash cart, and let the President take the foreign policy heat.

It’s not just that OCO creates an “anything goes” atmosphere at the Defense Department, with no incentive to clean up waste or exercise restraint in military action. OCO provides a blueprint to constantly ratchet up war spending while crying poor about everything else. “This is Nobel-class chutzpah,” said Gordon Adams. “It’s not even being done in a smoke-filled room. It’s in public, which makes it even funnier.”